An Analysis of the Impact that Minnesota State Constitution, Article XIII Sec. 7 No License to Peddle has on the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s Ability to Regulate the Produce Supply

Katherine Simon

Minnesota Department of Agriculture

International Food Protection Training Institute

2010 Fellow in Applied Science, Law and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

Safe growing and handling practices relating to fresh produce are an increasing concern in public health as evidenced by recent large outbreaks traced to a variety of fresh produce sources. Mainstream industry specifications and regulatory oversight for fresh produce can minimize the risks associated with produce production. The State Constitution of Minnesota precludes the licensing of farmers for the sales of products grown or cultivated on the farm, which eliminates a key step in the regulatory oversight of fresh produce. The impact of the licensing exemption on the ability of the Minnesota Department of Agriculture to regulate the produce supply was evaluated using a policy analysis framework to develop evidence, determine potential options, and project outcomes. The options identified included remaining with the status quo for regulating farm sales of fresh produce, increasing the education and outreach associated with good agricultural practices and safe food handling through existing MDA programs, and revising the current policy for registering farms that process food products. The projected outcomes of the effective options were evaluated using the framework criteria.

Background

The weight of fresh fruits and vegetables on the scale of public health risk has increased significantly in recent years. Contamination of fresh produce with pathogenic microorganisms is of particular concern because produce typically does not undergo processing or cooking steps designed to kill pathogens (Acheson, 2007). Many on-farm conditions influence the potential contamination of produce with pathogens including weather, water sources, irrigation equipment, and the hygiene of human harvesters (Isaacson, Torrence, & Buckley, 2004). Recent large foodborne illness outbreaks linked to fresh produce have brought pre-harvest growing conditions and post-harvest handling practices for minimally-processed fresh produce to the forefront of the discussion regarding the effectiveness of the food safety system (Becker, 2009).

The mainstream produce supply chain typically involves multiple stages prior to consumption, which include growing, storing, packing or processing, distribution, and retail sales (Martinez, et al., 2010). These stages can be conducted by separate food-handling facilities that mitigate their own risk in relation to food handling by requiring their immediate suppliers to meet certain standards. These standards may include passing independent third-party audits or maintaining certifications for good agricultural practices (GAP) (Dimitri, Tegene, & Kaufman, 2003). Additionally, any facility located in Minnesota that performs a stage of produce handling, excluding growing, is required to apply for and maintain a food handling license from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture (Minnesota Consolidated Food Licensing Law, 1971). The licensing process includes a facility and process review to determine fitness for handling food as well as periodic risk-based inspections for sanitation and process controls (Dairy & Food Inspection Division, 2011). Industry and regulatory interactions jointly promote food safety in the mainstream produce distribution chain by ensuring that actions to minimize food safety risk are being implemented.

Local food marketing, of which fresh produce is a significant segment, has become an increased portion of US agricultural sales in recent years. This increase is a result of several different social movements including environmental sustainability, support for small farms, stimulating local economies, and awareness of food origins (Martinez, et al., 2010). Additionally, the demand for and supply of locally-grown foods has also increased. The number of US farmers’ markets tripled from 1994 to 2010 (Agricultural Marketing Marketing Service, 2011) and reports of community-supported agriculture organization (CSA) numbers are estimated to have a three-and-a-half fold increase from 400 to over 1400 in the last 10 years (Martinez, et al., 2010). Direct sales by farmers to end users removes mainstream industry interactions that influence the implementation of practices to minimize food safety risks related to fresh produce production and handling. At this point, it is unclear how many direct-marketing farms are also conducting additional food processing activities such as chopping, freezing, or drying (Becker, 2009).

Many guidance documents targeted at the produce industry have been developed for controlling the food safety risks involved with growing and handling fresh produce. This includes the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Guidance for Industry: Guide to Minimize Microbial Food Safety Hazards of Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables (2009). Guidance for food regulators and educational outreach programs interacting with the fresh produce industry has also been developed, including the Association of Food and Drug Officials’ Model Code for Produce Safety (2010) and the Joint Institute for Food Safety and Nutrition’s GAPs Manual (2010). These resources have limited influence on the produce industry due to the resources’ status as “recommendations,” not regulation (Johnson, Lister, Williams, Burrows, Upton, & Monke, 2010). This status may change in the future. The 2011 FDA Food Safety Modernization Act, signed into law by President Obama on January 4, 2011, includes regulatory rulemaking for produce standards to minimize risks of foodborne illness that is flexible for application in diverse production types and sizes. An exemption from the requirement to meet the new standards was included for farms from which the majority of products are sold directly to consumers or end users.

However, the existence of a regulation does not guarantee that standards are being met. Regulatory authority and enforcement authority are necessary for food safety regulators to ensure compliance with the law. In Minnesota, this may be completed through the creation or adoption of laws and through the establishment of a licensing system to allow enforcement of the laws. However, Article XIII Sec. 7 of the Constitution of the State of Minnesota (1998) states: “Any person may sell or peddle the products of the farm or garden occupied and cultivated by him without obtaining a license.” The Minnesota Consolidated Food Licensing Law (MN Statute Chapter 28A) was enacted in 1971 and cannot violate the State Constitution, thereby necessitating a statutory exemption for requirement of a food-handling license.

Problem Statement

Without licensing authority, enforcement leverage for compliance with sanitary food handling practices is restricted. The shortened distribution chain created by increased direct farm marketing eliminates the mainstream market pressures that reduce food safety risk. Without regulatory enforcement or traditional market-driven production and quality standards, the potential exists for increased public health risk of exposure to sources of foodborne illnesses related to fresh produce growing and handling practices. By examining the impact of the licensing exclusion for sales by farmers, food safety and public health regulators in Minnesota will have a greater awareness of the position in regulatory oversight held by fresh produce farmers who are not licensed in Minnesota. An understanding of the influence on food safety and public health will also allow policy makers to determine if changes are needed regarding the current relationships MDA programs have with local fresh produce suppliers. The identification of necessary changes will allow for more effective planning regarding state funding as well as staffing and other resource allocations. This identification of necessary changes has the potential to improve the safety of the fresh produce supply in Minnesota and to provide strategies for regulating the fresh produce supply in other states.

Research Question

What is the impact of Article XIII Section 7 of the Constitution of Minnesota, “No license required to peddle,” on the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s ability to regulate the fresh produce supply?

Methods

The framework for policy analysis proposed in Health Policy Analysis: A Simple Tool for Policy Makers by T. Collins (2005) was used to develop evidence relating to the topic. Policy options and projected outcomes were then proposed and evaluated against the framework criteria.

Evidence

The Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s (MDA) mission statement is “to enhance Minnesotans’ quality of life by ensuring the integrity of the food supply, the health of the environment, and the strength of the agricultural economy” (Minnesota Department of Agriculture, 2011). MDA has multiple divisions that provide functions to the public involving agriculture. The Dairy & Food Inspection Division (DFID) carries out the duties of regulating the food supply while the Ag Marketing & Development Division promotes agricultural products in Minnesota. All divisions within MDA are overseen by the Commissioner of Agriculture.

MDA also has programs, along with federal agencies, that offer promotional and incentive programs to encourage farm sales of fresh produce. MDA maintains a licensing system for use of the “Minnesota Grown” logo that also includes advertising in the state-issued Minnesota Grown Directory for an additional fee. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) offers numerous programs encouraging direct marketing of fresh produce through various agencies including Specialty Crop Block Grants, Value-Added Producer Grants, and the Farmers’ Market Promotion Program (Grants, Loans & Support, 2011). MDA offers many loan assistance programs designed to increase Minnesota agricultural production such as farm purchasing, capital improvements, sustainable farming practices, and value-added production plans. Some MDA loan programs require farm business management training commitments as part of the application process (Minnesota Department of Agriculture, 2011). MDA also assists in implementing the USDA Fresh Produce Audit Verification Program, a voluntary program for farmers and others involved in the fresh produce distribution system to request fee-based inspections for adherence to Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs). USDA Audit Verification Program inspections are routinely conducted by state auditors. In MDA, the voluntary GAPs audits are conducted through the Plant Protection Division as opposed to DFID (Agricultural Marketing Marketing Service, 2011).

Additionally, programs exist that are designed to encourage direct sales from farmers through specific populations. These populations include the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program, Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program, and the Farm-to-School Initiative (Grants, Loans & Support, 2011). Young children and elderly individuals, which are included in the targeted sales populations, are considered highly-susceptible populations because they are more vulnerable to foodborne diseases. Additional precautions to control risks associated with food production and handling are necessary when producing for highly-susceptible populations (Employee Health and Personal Hygiene Handbook, 2010).

In 2005, MDA’s interpretation that further processing of farm products, such as packaging, chopping, grinding, or drying, did not meet the definition of “product of farm or garden,” was challenged in the Minnesota Supreme Court. The Court determined that further processed farm products are still products of the farm and are constitutionally excluded from licensing. However, the Court also determined that farmers are not excluded from the need to meet all other regulations applicable to their products, such as sanitary handling and facilities (State v. Hartmann). After this decision, DFID released a Licensing Exemptions Policy Memo in 2006. The policy includes a no-fee registration and routine performance of risk-based inspections for farmers that sell further processed products of the farm or garden (Elfering, 2006). The policy does not include registration of farmers who are supplying solely unprocessed fresh produce for sale in Minnesota.

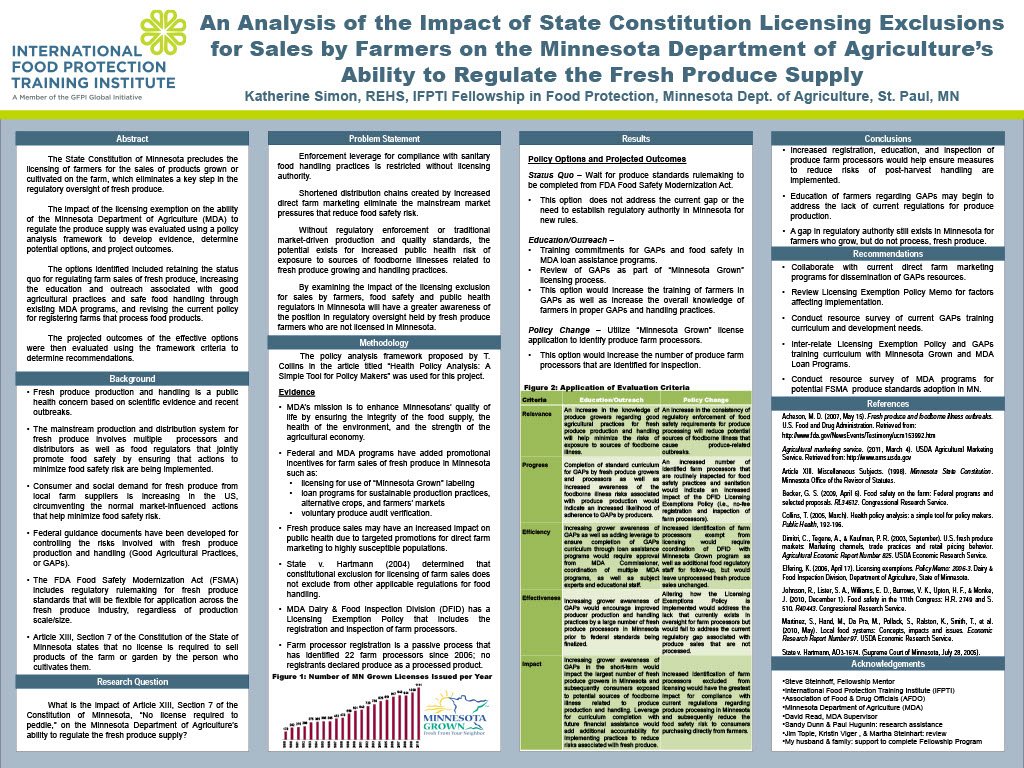

Approximately twenty-two (22) farms have been registered as farm processors based on the Licensing Exemptions Policy, of which only four (4) registered since 2008. Farm products that were declared as further processed included maple syrup, honey, and meat. No registered farm processors have declared processed produce as a product being sold (Dairy & Food Inspection Division, 2011). In 2010, 1111 licenses were issued to farmers for the use of “Minnesota Grown” logos (Figure 1). The disparity between the total number of logo licenses and registered farm processors raises the question as to the effectiveness of the policy on registering farm processors. The small proportion of farm processors registered may be due to the current passive process of becoming registered. Identification of farm processors relies on a combination of happenstance and farmers’ knowledge of licensing requirements for implementation. Food inspection staff must either encounter a farm processor selling during routine inspections of licensed facilities, receive a complaint regarding farm processor sales, or be contacted directly by the farmer (Elfering, 2006).

Results

The following options and outcomes were determined based on the evidence collected to address minimizing the risks associated with fresh produce growing and handling in Minnesota.

Options

Status Quo. Do not seek to change the regulation of farmers who produce and sell fresh produce directly to consumers or end users in Minnesota. With the signing of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act, rulemaking is in progress for fresh produce standards that, as currently envisioned, will be used by the retail food industry, fresh produce industry, and federal food regulators. The rules will ensure that measures to minimize the risks associated with fresh produce production and handling are in place for farms and processors included in the regulation.

Education/Outreach. Increase producer knowledge of measures to reduce the risks associated with produce production and handling through MDA programs. Training commitments specific to GAPs and safe food production could be requirements for receiving financial assistance from MDA loan programs when fresh produce sales or processing are identified as farm operations. Receipt and/or review of GAPs could also be used as part of the “Minnesota Grown” licensing process.

Policy Change. Revise the DFID Licensing Exemption Policy to include in the “Minnesota Grown” licensing process. Logo license applications could include a yes/no question to identify when fresh produce processing is occurring on the applicant’s farm. Affirmative responses could be referred to DFID for registration or licensing as applicable prior to placement in the Minnesota Grown Directory.

Projected Outcome

Status Quo. Maintaining the current policy for farmers selling fresh produce directly to end users does not address the potential food safety risks that currently exist in Minnesota’s fresh produce supply for several reasons. The current passive implementation of farm processing registration has not successfully identified any farm produce processors for inspection. Also, even if federal rulemaking for produce standards is accomplished, effective implementation in Minnesota would potentially require revisions of state law to grant MDA the authority to adopt and enforce federal produce standards in addition to the identification of affected farms. Further, a status quo approach would not allow for further resource review to determine which MDA program would be best prepared for future oversight and enforcement of fresh produce standards. Maintaining the status quo is not an effective option to address food safety issues affecting fresh produce farmers who are excluded from licensing.

Education/Outreach. Increased awareness and application of safe production and handling practices by fresh produce growers would help reduce the potential risks related to fresh produce production and handling. Reduction in food safety risks associated with produce production and handling would be of particular value to those farmers participating in targeted sales to highly-susceptible populations. Connecting these requirements to other MDA licenses or incentive programs would increase the likelihood of compliance with educational elements. Education and outreach would require additional resource allocation for revision and ongoing maintenance of the existing processes and programs, as well as the creation and delivery of accessible training curriculum. GAPs training curriculum, fact sheets, and resources would need to be created and available for use by the Minnesota Grown and MDA loan programs as well as applicants.

Policy Change. Inclusion of a farm produce processing question in the Minnesota Grown licensing application will potentially increase registration of produce farm processors. Greater registration of farm processors would increase the ability of MDA to ensure that handling practices designed to minimize risks related to fresh produce handling are being properly implemented. Approval for the policy revision may be difficult to obtain due to potential impacts on the promotion of agriculture in Minnesota, an equal mission of MDA. Prior to implementation, the additional resources that would be necessary to review and inspect newly-registered farm processing operations would need to be considered. This option does not address the fact that key portions of the production of fresh produce, specifically GAPs, do not currently fall within the regulatory authority of MDA.

Application of Evaluation Criteria

Enforcement of uniform federal standards for fresh produce, when they are finalized, would impact the produce industry as a whole and would reduce the potential for foodborne illness outbreaks associated with fresh produce over time. However, for the interim, education and policy change options would serve to increase assurance of adherence to GAPs and other food safety principles associated with fresh produce. The value of these options are evaluated and illustrated in Table 1 using an analytical method developed by T. Collins, “Health Policy Analysis: A Simple Tool for Policy Makers (2005).” Relying on the current regulatory strategy for fresh produce sales by farmers does not address the current gap in oversight that has been identified.

Conclusions

Minnesota currently has a gap in regulatory oversight of the produce supply due to the constitutionally-imposed constraints on the licensing of growing and handling practices for farmers who sell fresh produce directly to consumers and end users. Increased registration, education, and inspection of farm processors who market directly to consumers would increase the ability of MDA to ensure that measures to reduce public health risks associated with post-harvest processing of fresh produce are implemented. Education of farmers regarding safe produce-growing may begin to address the lack of current regulations for produce production. However, a gap in regulatory authority would still exist in Minnesota for farmers who grow, but do not process, fresh produce. Federal regulations for produce standards need to be finalized and enforcement authority for those regulations must be established in Minnesota before state verification of compliance with these federal regulations could begin.

Recommendations

Collaboration with the Minnesota Grown Program and Farm-to-School coordinators to ensure that all currently-available resources relating to GAPs are being disseminated is imperative. Additional review should be conducted on the current use of the DFID Licensing Exemptions Policy to determine if unidentified factors explain the small number of farm processors currently registered and the lack of produce processors listed. Resource surveys should be conducted to help establish and maintain accessible training curriculum for GAPs in Minnesota, potentially through collaboration with existing university extension programs. Policy-making decisions for inter-relating DFID Licensing Exemption Policy and GAPs training curriculum with Minnesota Grown licensing and MDA loan assistance programs needs to be explored for department approval. MDA program resource surveys must be initiated to determine the proper assignment for regulatory oversight of FDA produce standards for future staffing and training needs.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Steve Steinhoff, my mentor in the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) Fellowship Program, for all the support that I received while completing this project and the program. His ability to guide my thoughts without determining my final destination allowed me to experience genuine development in this process. I would also like to thank IFPTI and all those individuals behind the scenes that allowed the Fellowship Program, and all the fantastic opportunities that stemmed from it, to be available. The cohort of Fellows also deserves my appreciation for the Fellows’ support in the completion of my project as well as sharing the participants’ experiences and opinions. The program instructors were invaluable for the instructors’ ability to impart knowledge, challenge our perceptions, and raise the expectation of ourselves. My supervisor, David Read, as well as my agency, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, needs recognition for allowing me the time to participate in this experience. Sandy Dunn and Paul Hugunin from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture provided research assistance. Martha Steinhart, Kristin Viger, and Jim Topie, also from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, provided valuable support in review. I would like to thank the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO) for the generous invitation and assistance in attending the 2011 Annual Educational Conference. I owe special appreciation to my husband and my family for showing unending support in allowing me the ability to complete the IFPTI Fellowship Program.

Corresponding Author:

Katherine Simon, Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Email: katherine.simon@state.mn.us

References

Acheson, M. D. (2007, May 15). Fresh produce and foodborne illness outbreaks. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Testimony/ucm153992.htm

AFDO model code for produce safety. (2010). Association of Food & Drug Officials. Retrieved from http://www.afdo.org/Resources/ProduceSafety.cfm

Agricultural marketing marketing service. (2011, March 4). USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. Retrieved from: http://www.ams.usda.gov

Article XIII. Miscellaneous Subjects. (1998). Minnesota State Constitution . Minnesota Office of the Revisor of Statutes.

Becker, G. S. (2009, April 6). Food safety on the farm: Federal programs and selected proposals.

RL34612 . Congressional Research Service.

Collins, T. (2005, March). Health policy analysis: a simple tool for policy makers. Public Health, 192-196.

Dairy & Food Inspection Division. (2011, March 1). Minnesota Department of Agriculture .

Dimitri, C., Tegene, A., & Kaufman, P. R. (2003, September). U.S. fresh produce markets: Marketing channels, trade practices and retail pricing behavior. Agricultural Economic Report Number 825. USDA Economic Reserach Service.

Elfering, K. (2006, April 17). Licensing exemptions. Policy Memo: 2006-3. Dairy & Food Inspection Division, Department of Agriculture, State of Minnesota.

Employee health and personal hygiene handbook. (2010, January 1). U. S. Food and Drug Administration Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/IndustryandRegulatoryAssist anceand TraininIndustryan/ucm184170.htm#susc

GAPs manual. (2010, August). Joint Institute for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Retrieved from http://jifsan.umd.edu/training/gaps.php

Grants, loans & support. (2011). Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food. Retrieved from http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/knowyourfarmer?navtype=KYF&navid=KYF_GR ANTS

Guidance for industry: Guide to minimize microbial food safety hazards for fresh fruits and vegetables. (2009, November 25). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocume nts/ProduceandProduceandPl/ucm064574.htm

Isaacson, R. E., Torrence, M., & Buckley, M. R. (2004). Preharvest food safety and security. American Academy of Microbiology.

Johnson, R., Lister, S. A., Williams, E. D., Burrows, V. K., Upton, H. F., & Monke, J. (2010, December 1). Food safety in the 111th Congress: H.R. 2749 and S. 510. R40443. Congressional Research Service.

Martinez, S., Hand, M., Da Pra, M., Pollack, S., Ralston, K., Smith, T., et al. (2010, May). Local food systems

Concepts, impacts and issues. Econmic Research Report Number 97. USDA Economic Research Service.

Minnesota consolidated food licensing law. (1971). Minnesota State Statute Chapter 28A. Minnesota Office of the Revisor of Satutes.

Minnesota Department of Agriculture. (2011). Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.mda.state.mn.us

Minnesota Grown Program. (2011, March 1). Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

State v. Hartmann, AO3-1674 (Supreme Court of Minnesota July 28, 2005).