Food Safety Study: Shared Kitchens in the Washington, D.C. Metro Area

Jemal Yasin

Sanitarian, District of Columbia Department of Health

Abstract

Shared Kitchens (SK) are licensed commercial kitchens where tenants share spaces to operate food-based businesses. The utilization of SKs has been on the rise in the United States. There are several SKs with multiple tenants operating in the Washington, D.C. metro area. This research provides baseline information on the food safety practices of SKs in the Washington, D.C. area. SK inspection data from Washington, D.C. and Fairfax County, Virginia food safety inspection systems—along with survey data from SK operators, SK tenants and food program supervisors from the health departments—was collected and analyzed. The data show SK utilization has increased in the past three years, there are no specific regulations for SKs, and the requirements for licensing SKs and their tenants vary by jurisdiction. The most frequently cited violations included: no certified food protection manager present; food not protected from contamination; ready-to-eat foods not date marked or disposed of in a timely manner; and handwashing facilities not supplied or inadequate. SKs require tenants to obtain proper licenses from regulatory agencies before beginning operators, and SKs provide tenants with standard food safety operating procedures. Low initial investment cost was the main reason for tenants to start businesses in SKs. The researcher recommends development of food safety policies tailored to SKs to enhance food protection.

Key words: Shared kitchens, commissary, retail food safety regulation, caterers, food safety violations

Food Safety Study: Shared Kitchens in the Washington, D.C. Metro Area

Background

Shared Kitchens (SKs) are licensed commercial kitchens where licensed food establishments or tenants share space to operate food businesses. The tenants operating in SKs produce diverse food products (Stucker, 2017). The majority of tenants operating in SKs produce ready-to-eat products, like sandwiches, cookies, salads, and artisanal foods such as breads, cheeses, and canned products (Wodka, 2020).

SK tenants also produce “value-added products” (Conover, et al, 2015). The USDA defines value-added food products as having “a change in physical state or form of the product.” Examples include making noodles or pasta from wheat flour, or baking different kinds of pastries from flour, butter, and other ingredients to enhance the original ingredient values.

SKs vary in size and business structure across the United States. Their sizes range from 1,000 to 50,000 square feet. SKs are found in rural areas, Native American territories, and suburban and urban areas. SK business structures include individual owners; corporate operated, nonprofit or government operated; or university-sponsored (Colpaart, 2018). SKs exist in 48 states as well as the District of Columbia (Wodka, 2020).

Like the various products SK tenants produce, their business functions also are wide ranging. Tenants cater products at events or sell at farmers’ markets, retail, and wholesale outlets, or on food trucks or food carts. In addition, increasingly more food businesses sell products on the internet and through home delivery services.

As a result of a recent rise in online food ordering and delivery services from retail establishments in North America—and the COVID 19 pandemic’s impact on the retail food industry—SKs are becoming more popular with culinary entrepreneurs as they present significant advantages for ease of starting and operating a new food business (Yang, 2020 and Minaker, 2021).

The number of SKs in the United States increased by 50% between 2013 and 2016 to more than 200 facilities (Wodka, 2016). The utilization of SKs is expected to steadily increase in the future as SKs are supporting the current popular “artisanal food movement, the sharing economy, and the current spike in entrepreneurship as a career” (Wodka, 2020). In addition to the aforementioned causes, increased online shopping for ready-to-eat foods, and demand for locally manufactured food products are important factors that may affect how SKs are utilized in the United States.

This research aimed to collect and analyze data on SKs located in the Washington, D.C. metro area; to understand the SK licensing and food safety regulatory requirements; to identify SK owners and/or manager responsibilities in relation to food safety; to define the types of food operations; to identify prevailing food safety challenges inspectors from health departments observe during inspections at the SKs; and to identify factors contributing to the utilization of SKs in the study area.

Problem Statement

A baseline research report to understand the food safety practices, licensing and regulation activities of SKs located in the Washington, D.C. metro area is lacking.

Research Questions

1. What factors contribute to the utilization of SKs in the Washington, D.C. metro area?

2. What are the food safety regulatory requirements for SKs in the Washington, D.C. metro area?

3. What are the food-safety related responsibilities of SK operators in the Washington, D.C. metro area?

4. What types of food establishments operate in SKs in the Washington, D.C. metro area?

5. What are the primary food safety violations observed in SKs in the Washington, D.C. metro area?

Methodology

For this research the “Washington, D.C. metro area” is defined as Washington, D.C., Montgomery, and Prince George’s counties in Maryland, and the counties of Fairfax and Arlington, and the City of Alexandria, in Virginia.

In Phase one, data were drawn from the Washington, D.C. Digital Health Department inspection system and the Fairfax County, VA, electronic inspection system to analyze for the prevailing food safety violations observed in SKs.

In Phase two, data about licensing and food safety regulatory requirements, factors contributing to the utilization of SKs in the past three years, and type of food operation in SKs was obtained from supervisory sanitarians, working in each study jurisdiction, through selective response and open-ended survey questions. Links to the survey questions on the Survey Monkey app were e-mailed to supervisory sanitarians.

In Phase three, data about SK operators’ food safety and licensing responsibilities, and factors contributing to the utilization of SKs was obtained from SK operators and SK tenants, through selective response and open-ended survey questions. Links to the survey questions on the Survey Monkey website were e-mailed to SK operators and tenants.

In Phase four, the researcher analyzed the data to determine results, draw conclusions and develop recommendations.

Results

Food protection program supervisors from each study jurisdiction responded that no specific regulations exist to regulate SKs, aside from the food safety regulations governing all retail food establishments in each respective jurisdiction.

The licensing requirements for SK tenants vary from one jurisdiction to another. For example, in Prince George’s County, Maryland, the tenants must provide a letter to the licensing authority from the SK owner authorizing their use of the SK. Whereas, in Washington, D.C., tenants can present lease agreements or certificates of occupancy from the SK that they are planning to operate to D.C. Health. In addition, 92% of SK tenants surveyed in Washington, D.C. responded that SK management requires them to obtain a license prior to starting to operate.

The food protection program supervisors from all jurisdictions responded that most food establishments operating in the SKs were doing business as caterers. However, names used to denote caterers could differ from one jurisdiction to the other. Table 1 shows the terms used to denote SKs in each jurisdiction.

Table 1

Terms used to denote SKs in each jurisdiction

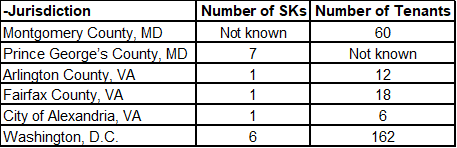

The supervisors’ responses to the number of SKs and tenants in operation at the time of survey is indicated in Table 2. The number of SKs in Montgomery County, MD was not known as there has not been specific delineation for SKs from the other retail food establishments. The supervisor from Montgomery County, MD responded that an estimate of 60 tenants were operating in SK settings in the county, and plans were being put in place to have clear delineation for SKs in the county. There was no data to report for the number of tenants operating in the SKs in the Prince George’s county during the survey period.

Table 2

Number of SKs and tenants in each study jurisdiction.

Food protection program supervisors from all jurisdictions responded that SK utilization has increased—except within the City of Alexandria, VA—in the past three years due to the cost of doing business, the COVID 19 pandemic, and the availability of food delivery services apps to distribute products. The supervisor at the City of Alexandria, VA responded that SK utilization in the past three years has remained steady.

All of the surveyed SK operators from Washington, D.C. (6) responded that they require tenants to obtain business licenses before starting operations in their SKs. Additionally, two SK operators responded they will allow tenants to conduct research and development work, or build recipes in their SK before obtaining licensing from an authorized government authority, but they will not allow tenants to sell products to consumers.

All six surveyed SK operators from Washington, D.C. responded that cleaning food and non-food-contact surfaces in the respective SK is a shared responsibility among tenants. Tenants are responsible for cleaning their personal kitchenware. The SK management is responsible for cleaning shared food preparation tables, storage shelves, refrigeration units, cooking lines, floors, walls, and restrooms. No survey responses were obtained from SK operators operating in other jurisdictions.

Ninety-two (92%) percent (12) of SK tenants in Washington, D.C. responded that they operate based on written food safety operating procedures that SK management provided them. The Washington, D.C. SK tenants gave a 4.4 out of 5.0 rating for the proper implementation of written food safety procedures in the SKs where they operate. Moreover, 54% of the SK tenants (7) responded that the SK management provided them “some level” of food safety training.

SK tenants in Washington, D.C. responded that the following are the main factors motivating them to start food businesses in SKs: cost; lower overhead; lower initial investment cost; less financial risk; and affordability to start a business compared to starting new brick and mortar food establishment, such as restaurant, delicatessen or grocery store. No survey responses were obtained from SK tenants operating within the other jurisdictions.

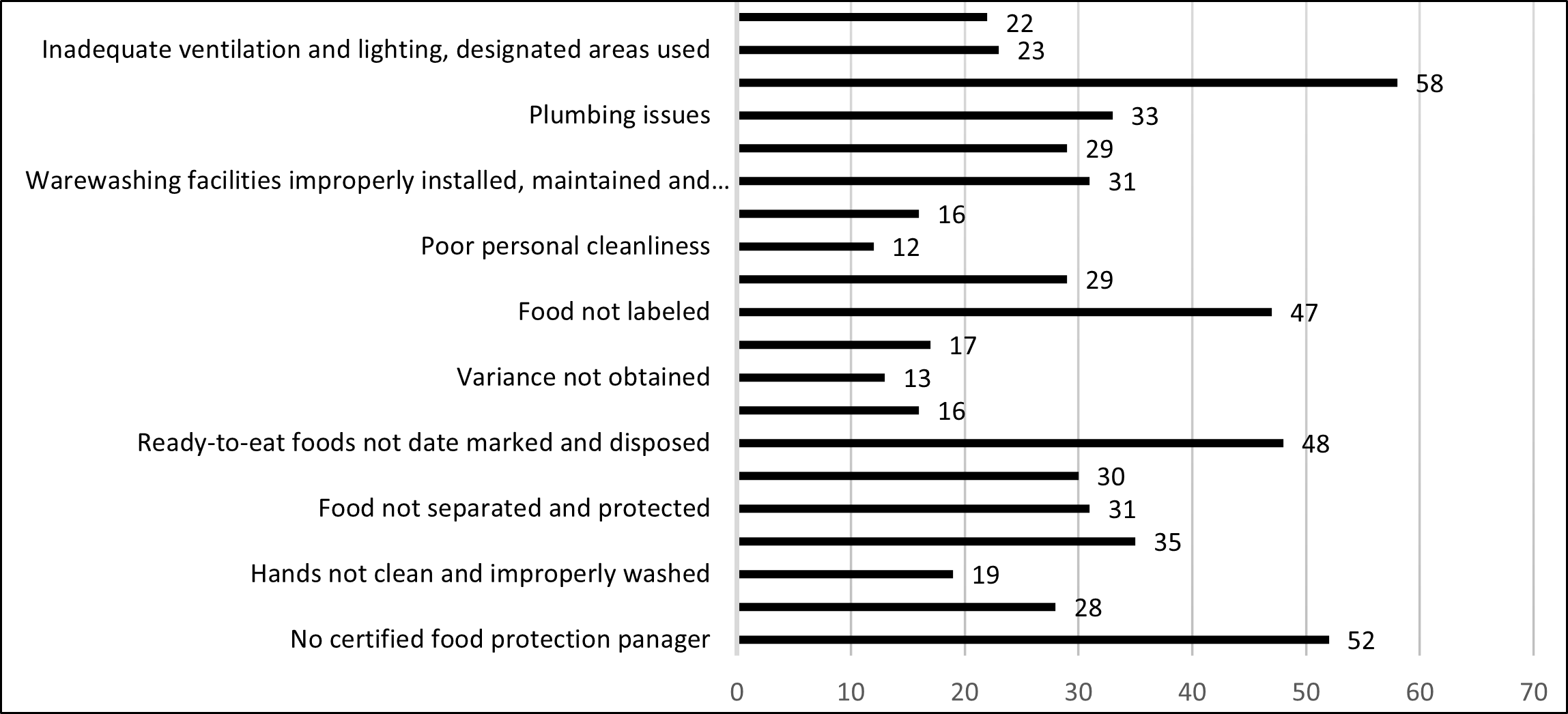

According the SK data drawn from Washington, D.C. Digital Health Department electronic inspection software, D.C. Health conducted 483 inspections and observed 742 violations at SKs between 2014 and 2021. The most frequently cited violations are shown in Graph 1 below include:

1. Physical facilities improperly installed, maintained, and cleaned;

2. No certified food manager on duty;

3. Ready-to-eat foods not date marked or disposed of;

4. Food not labeled;

5. Inadequate hand washing sinks or hand sinks not supplied;

6. Inadequate plumbing; and

7. Food not separated and protected from contamination,

Graph 1

Types and number of Violations Observed in Washington, D.C. SKs between 2014 and 2021

While inspectors from D.C. Health observed the violations indicated above, the SK tenants in Washington, D.C. responded that they perceived the following as the major food safety concerns for their businesses and clients while operating in a SK setting:

1. Allergy cross contamination from shared food contact surfaces like food preparation tables and dishwashing facilities.

2. Cross contamination from an improper hierarchy of food storage in shared shelving units inside walk-in and reach-in refrigerators and freezers.

3. Improper cleaning of shared food and non-food contact surfaces.

Fairfax County, VA health department conducted 68 inspections at 24 caterers operating in SKs between 2017 and 2021. Of the 68 inspections, the department observed no violation in 47 inspections. The department cited nine SK tenants for not having a certified food manager on duty during inspection. The Fairfax County Health Department inspectors also cited two SK tenants for lack of sanitizer test strips, and one time each for the following violations:

1. Lack of heat test strips;

2. Improper holding, cooling and cooking temperatures;

3. Ready-to-eat (RTE) foods stored in refrigeration more than seven days;

4. No variance obtained for poached eggs; and

5. Poor maintenance of a refrigeration door gasket.

There was no inspection data analyzed for the other jurisdictions.

Conclusions

Based on the data collected and analyzed in this research, the following conclusions were drawn:

1. In all jurisdictions, aside from licensing, there were no food safety regulations specific to SKs. The SKs have been regulated based on the general food safety regulations for retail food establishments, such as restaurants or delicatessens.

2. While the list of requirements for licensing vary from one jurisdiction to another, all jurisdictions require both SK operators and tenants to be licensed and to operate in full compliance within the retail food safety regulations applicable in their respective jurisdiction.

3. The tenants operating in the SKs were largely identified as “caterers” in all jurisdictions. These caterers prepare different kinds of value-added food items and sell products to local consumers. Additionally, the terms used to denote the SK tenants sometimes differs between one jurisdiction to the other.

4. The SKs in Washington, D.C. require tenants to obtain appropriate licenses from regulatory agencies before starting to operate. Similarly, SKs provide written food safety operating procedures and the majority of SK tenants in Washington, D.C. are satisfied with how these food safety operation procedures are implemented in the SKs. Additionally, the majority of the SK operators in Washington, D.C. provide some level of food safety training to their tenants.

5. “No certified food protection manager on duty" was one of the most frequently cited violations. This food safety violation alone may be a contributing factor to any number of food safety issues.

6. SK utilization has increased in the past three years, except in the City of Alexandria, VA, and the trend is most likely to continue in the future due to the effect of the COVID 19 pandemic on traditional retail food establishments and the availability of food delivery service apps.

Recommendations

This study is a small-scale baseline research study aimed at understanding SK operations in the Washington, D.C. area, from the food safety regulations and licensing perspectives. With that in mind, the researcher respectfully offers the following recommendation:

1. Develop educational activities, with regulators or academia, to improve food safety knowledge and practices of SK management and tenants, to decrease food safety violations.

2. Develop a document, by regulatory agencies, that emphasizes the importance of a certified food safety manager being present during operation of SKs.

3. Develop standardized food safety policy or regulations tailored to SK settings to prevent potential cross contamination from shared food and non-food contact surfaces.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge all of the following:

· IFPTI organization and its staff, in general, for giving me the opportunity to participate in Cohort X fellowship program.

· Mr. Doug Saunders, my research mentor, for the trainings he has provided me and his constructive comments on the research work.

· Ms. Kathy Fedder for her guidance when developing the research proposal and trainings she provided me.

· Mr. Gerald Wojtala and Dr. Craig Kaml for critiquing the research proposal, research report and presentations.

· Dr. Chris Weiss for compiling and emailing me the survey data from the Survey Monkey website.

· My supervisor, Mrs. Joyce Moore, and Ms. Victoria Grover, the program manager for the Food Division of the Washington, D.C. Health Department for granting me the time to participate in the fellowship program.

· Mrs. Sion Smith, Mr. Pieter Sheehan, Ms. Adrian Joye, and Mr. John Yetman, from Fairfax County, VA Health Department for providing me the SK inspection data and encouragement during the data collection, analysis and writing of this paper.

· All of the SK operators, owners, tenants and supervisory sanitarians from health departments, who participated in the surveys.

· Last but not least, my families for their support as I was participating in the program.

References

Brar, K., Minaker, L.M. (2021). Geographic reach and nutritional quality of foods available from mobile online food delivery service applications: Novel opportunities for retail food environment surveillance. BMC Public Health. 21, 458. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10489-2

Colpaart, A. (2018). The shared kitchen model, emerging and evolving, The Food Corridor. https://www.thefoodcorridor.com

Conover, E., Rubchinuk E., Smith S., & Cortez Y. (2015). History of shared-use commercial kitchens: A case study analysis of kitchen success. Community Engaged Research Reports. 30. SCARAB: Digital Commons@Bates https://scarab.bates.edu/community_engaged_research/30

Stucker, H. (2017). Kitchen incubators in New England: How an emergent business incubator model is fostering food entrepreneurship: A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Urban Environmental Policy and Planning. Tufts University. Tufts Digital Library. https://dl.tufts.edu/concern/pdfs/n8710326t

Wodka, A., Heller, G., Huang, L., Mannino, A. L., Clouet, B., Goldberg, C. H., Osei-Bonsu, F., Johnson-Piett, J., & Passerini, C. (2016). U.S. kitchen incubators: An industry update. ACT, Econsult Solutions Inc., and Urbane Development. https://www.actimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/U.S.-Kitchen-Incubators-An-Industry-Update_Final.pdf

Wodka, A., Huang, L., Ho, L., DeCesare, M., Connor, B., Olney, N., Herrin, T., Corkan, H., Barca, A., Lodge, S., MacLennan, K., Baroff P., O’Toole, F., Johnson-Piett, J., Lagos, A., & Colpaart, A., (2020). U.S. kitchen incubators: An industry update. ESI Econsult Solutions Inc, Urbane Development, The Food Corridor, Catharine Street Consulting. https://econsultsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Kitchen-Incubators-2019_1.14.20.pdf

Yang, Y., Liu H., & Chen X., (2020). COVID-19 and restaurant demand: Early effects of the pandemic and stay-at-home orders, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/0959-6119

Author Note

Jemal Yasin, Sanitarian

District of Columbia Department of Health

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort X.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to:

Jemal Yasin, District of Columbia Department of Health

Funding for the IFPTI Fellowship in Food Protection Program was made possible by the Association of Food and Drug Officials