Assessment of Emergency Responses in Scott County, Iowa, Retail Food Establishments Following the August 2020 Derecho

Logan Hildebrant

Environmental Health Specialist, Scott County Health Dept.

Abstract

Emergency preparedness is an important topic when applied to food safety, but it also is an often-overlooked topic when viewed from the perspective of individual food handling facility preparedness. In August 2020 a massive and rare thunderstorm called a derecho caused widespread power blackouts in the Scott County area that lasted anywhere from hours to weeks. Surveys were conducted in the Scott County area by standardized environmental health inspectors to evaluate facilities’ emergency preparedness plans which were in place prior to the derecho. Surveys aimed to determine how many facilities had plans to address emergency situations before the derecho; how closely those plans resembled guidance developed by the national 2014 Conference for Food Protection; and how facilities affected by the mass power outages responded to ensure the safety of food stocks. Response data found significant differences between locally owned and corporate run facilities’ approaches to emergency preparedness, along with disparities around local operators’ knowledge with regard to safety parameters for time and temperature, monitoring, and methods to preserve cold food temperatures. Conclusions drawn from the study indicate improved emergency preparedness by facilities could help salvage foods during an emergency, while limiting the chances of cold foods becoming compromised and unsafe. This study presented a clear case for Scott County Health Department to improve education and reference materials that are provided to facility operators to enhance their knowledge on emergency planning.

Key words: Food safety, emergency preparedness, natural disasters, power outage, food handling practices.

Assessment of Emergency Responses in Scott County, Iowa, Retail Food Establishments Following the August 2020 Derecho

Background

The increased risk of illness outbreaks after a large natural disaster has long been a concern for public health preparedness. Natural disasters are atmospheric, geologic, and hydrologic events that cause great damage or loss of life. In the past two decades, natural disasters have killed millions of people and have caused adversity for over a billion by inducing disease and economic damages (Watson, 2007). Countries with robust sanitations systems may be less likely to suffer life threatening disease outbreaks resulting from natural disasters, however, disasters still may have an adverse impact on public health. In 2003, an increase in diarrheal illness was noted in the aftermath of a massive power outage that affected 9 million people in New York City. This increase was detected by using New York’s syndromic surveillance system, which monitors hospital emergency department visits, pharmacy sales data, and employee absenteeism. A case-control study was performed as part of an outbreak investigation, and associated the rampant and widespread cases of diarrheal illness with the consumption of meat and seafood after a mass electrical service interruption affecting 8 million New York City residents (Mark, 2006).

Natural disasters also may inflict a huge financial impact on retail food establishments by adding workloads, material cost, contributing to loss of inventory, and loss of business. Small and financially insecure establishments may be motivated to limit financial burden by saving questionable food inventory, thus compromising community safety. Therefore, the need for establishments to develop emergency planning procedures is critically important in order to limit the cost of potential disasters, but more importantly to ensure the safety of food stock. In 2014, the national Conference for Food Protection (CFP) assembled a guidance document that aimed to help facility owners think of and prepare for events that could interrupt services such as natural disasters, fires, and sewage backups.

On August 10, 2020, a massive meteorological event hit Scott County, Iowa and the surrounding area. This powerful storm tore through the region at 1:30 p.m. EST on a Monday afternoon and lasted for approximately one hour. This rare kind of storm is known as a derecho. A derecho is defined as a straight-line windstorm produced by a band of thunderstorms creating continuous or intermittent damage, over a distance of at least 400 miles long and 60 miles wide (Corfidi, 2022). The storm that struck the Midwest on August 10, 2020 traveled over 770 miles from South Dakota through Ohio with winds in several regions measuring at 100-110 mph. Wind of this velocity results in thunderstorms similar in power to that of a hurricane (Wolf, 20200).

Regional data from the Mid-American Energy Company in Scott County reported more than 125,000 homes and businesses without power for a duration of 24 hours to 1.5 weeks. With a population of 174,669, the volume of homes and facilities affected placed a significant burden on private and governmental resources and may have led to significant increases in foodborne illness risk factors (Clark, 2020).

Problem Statement

The level of emergency preparedness of food service establishments in Scott County, Iowa is unknown.

Research Questions

What percentage of retail food establishments had any food emergency response procedures prior to the derecho?

How closely did those procedures match the 2014 Conference for Food Protection emergency response guidelines?

What were the most common actions taken by establishments after the derrecho to maintain cold food tempertures?

How closely did actions match emergency response guidelines from the 2014 Conference for Food Protection?

Methodology

Survey data was gathered by four standardized Scott County Health Inspectors during routine food establishment inspections conducted from January 1 to March 4, 2022. Surveys were comprised of three parts: Part A consisted of questions to establish which facilities had Emergency Action Plans (EAPs) prior to the derecho event and how closely those plans related to guidance by the 2014 Conference for Food Protection (2014 CFP). Part B of the survey asked whether facilities experienced a loss of power, the duration of the power loss, and what actions were employed by the facility to ensure the safety of cold foods. Part C collected data on ownership.

During Part A, facilities which reported having preparedness plans were assessed for food handling procedures and methods for maintaining cold food temperatures that aligned with guidance identified in the 2014 CFP document.

During Part B, survey participants who reported being affected by power outages were asked to provide details on how they responded to ensure the safety of their cold foods. Respondents were asked if they took food temperatures, recorded times when temperatures were taken, what if any methods they employed to maintain cold food temperatures, and how operators decided when to discard potential time-temperature abused foods. Respondent data for methods used to keep foods cold were grouped into six categories relating to emergency cold holding methods provided in the 2014 CFP guidance document. The response categories were: 1) grouping foods together; 2) keeping cooler doors closed; 3) use of an alternative power source; 4) moving foods to safe cold holding locations; 5) using cooling agents such as ice/dry ice; and 6) the use of insulation.

Part C collected data on ownership characteristics with one group consisting of facilities owned and run by corporations, and the other group being facilities that were locally owned and operated.

Data then were analyzed to determine the level of emergency preparedness in Scott County, Iowa food facilities at the time of the 2020 derecho.

Results

A total of 56 surveys were conducted in person by Scott County health inspectors. Of the facilities sampled, 36 were locally run and 20 were corporate run. The percentage of facilities experiencing power loss during the 2020 weather event was recorded at 53 percent of the 36 locally run facilities, and a rate of 50 for the 20 corporate run facilities, with a median self-reported time for power loss of 54 and 55 hours, respectively.

Survey data for locally run facilities found 36 percent of respondents reported having an EAP in place before the derecho. Eighty percent (80%) of corporate run facilities were found to have an EAP established prior to the weather event.

Of the 13 local facilities that had EAPs, 92 percent were found to include procedures for facility operators to maintain cold food temperatures. Corporate run facilities that reported having an EAP had a 100 percent response rate for having procedures with methods outlined in the 2014 CFP guidance for keeping foods cold.

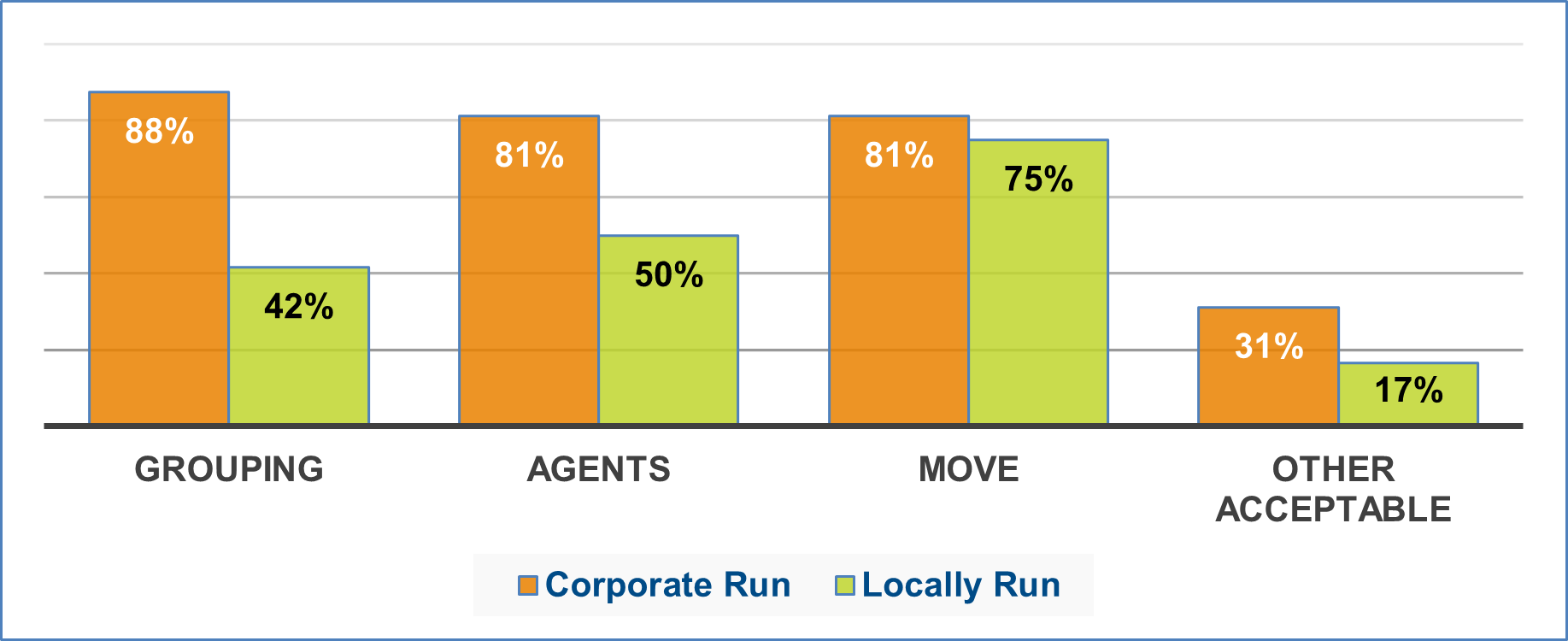

Graph 1 provide summaries for both local and corporate run facilities. Data is presented as percent of EAP’s which aligned with methods provided in 2014 CFP guidance for maintaining cold food temperatures during a power outage. Surveys revealed local facilities’ EAPs contained procedures for moving cold foods 75 percent of the time. Local EAPs were found to have a rate of 50 percent or less utilization of all other methods provided in the 2014 CFP guidelines. Corporate run facilities were found to have EAP procedures similar to the 2014 CFP guidelines more than 80% of the time for all methods listed in the 2014 CFP guidance document.

Graph 1

Local and corporate run response data for methods used to maintain cold holding temperatures

Survey participants who reported to have EAPs prior to the derecho, were found to have procedures for monitoring temperatures of cold foods during power outages lasting longer than four hours at a rate of 62 percent for locally run facilities, and 100% for corporate run facilities. EAPs were found to have procedures for deciding when to discard foods outside of normal operating time/temperatures 92 percent of the time for locally run facilities, and 93 percent of the time for corporate run facilities. Procedures were compared to the 2014 CFP guidance document and then categorized into groups as “Meet” (food handling procedures the same as the CFP guidelines), “Exceed” (cold foods discarded in excess of CFP guidelines), “Indeterminate” (not enough info to evaluate), and “Hazardous” (food handling procedures outside of CFP guidelines). Local and corporate facility response data is presented in Graphs 2 and 3 as percentages that were calculated by the total number of responses in a category divided by the total number of EAP’s with food handling procedures. Locally run facilities reported food handling procedures that met or exceeded the 2014 guidelines approximately 54 to 70 percent of the time for all temperature ranges. EAPs from local facilities had food handling procedures with insufficient details to evaluate at a rate of 8 to 31 percent and were found to have procedures outside of CFP guidelines 8 to 31 percent of the time for all temperature ranges (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Locally run facilities response data for food handling procedures

Corporate run facilities which reported having EAPs with food handling procedures were found to have met or exceeded the 2014 CFP guidelines between 82 and 88 percent of the time, and had plans without enough detail to evaluate 13 to 19 percent of the time, for all temperature ranges. No corporate run facilities reported having food handling procedures that were outside 2014 CFP guidelines (Graph 3). Food handling procedures were found to exceed 2014 CFP guidelines for all temperature ranges 46 to 54 percent of the time for local facilities and 69 to 88 percent of the time for corporate facilities. Local facilities were found to “meet” or to be the same as CFP guidelines 23 percent of the time for temperature ranges for 41 F to 45 F, and 8 percent of the time for temperature range of 45 F to 50 F.

Graph 3

Corporate run facilities response data for food handling procedures

Of the locally run facilities that reported being affected by power loss from the derecho, 53 percent reported having taken temperatures and 32 percent reported having tracked the amount of time food cooling equipment was without power or the amount of time foods were out of temperature. Of the corporate run facilities that reported a power outage, 60 percent reported taking temperatures, and 60 percent reported recording times equipment or foods were out of temperature. Locally run facilities who lost power reported having to discard some or all cold foods at a rate of 58 percent, whereas 40 percent of affected corporate run facilities discarded some or all their cold foods. Two of the most common methods locally run facilities used for deciding when to discard cold foods were ‘discard unfrozen foods’ and ‘discard foods above 41° F’ (Graph 4). The two most common methods given by corporate run facilities for how they determined to discard were: ‘discard foods above 41° F’ and some combinations of time and temperature of cold foods (Graph 4).

Graph 4

Affected local and corporate response data for methods facility operators used to decide when to discard cold foods.

Locally run facilities that experienced power loss reported having taken actions to try and maintain cold food temperatures at a rate of 89 percent. The three most common actions taken by affected locally run facilities that match 2014 CFP guidelines were ‘moving cold foods,’ ‘alternative power sources,’ and ‘keeping doors closed.’ Corporate run facilities that experienced power loss reported taking actions to maintain cold temperatures 70 percent of the time. The most common actions reported to have been taken by affected corporate run facilities were ’move product’ and keeping cooler doors closed. (Graph 5).

Graph 5

Local run and corporate run facilities affected by power loss responses for methods used to maintain cold holding temperatures of foods.

Conclusions

Analysis of research results led to the following conclusions:

1. A disparity was found between the number of corporate run facilities (80 percent) and locally run facilities (39 percent) who reported having EAPs.

2. Local EAP’s had fewer methods for maintaining cold holding temperatures similar to 2014 CFP guidance than corporate EAPs (Graph 1).

3. Both local and corporate EAP food handling procedures for discarding foods, based on time and temperature, show a high frequency of discarding foods that may be salvaged by implementation of 2014 CFP guidelines (Graphs 2 & 3).

4. Facilities that rely on district managers, hotlines, or specially trained managers had high variability between EAP survey responses.

5. Local facilities were less likely than corporate facilities to monitor the duration of time food and equipment were outside of safe food handling temperatures.

6. The most common response method used by both local and corporate run facilities was to move foods off site to maintain cold holding temperatures during power outages.

7. Local facilities were less likely than corporate facilities to use a combination of time and temperature as a method for determining when to discard foods.

Recommendations

Based on the results found, the following recommendations were developed:

1. Scott County should provide educational resources for facilities to create EAPs.

2. Scott County should provide resources for facility operators for how to use time and temperatures to determine when foods can be salvaged or when foods need to be discarded, especially during or after a natural disaster.

3. Plan local workshops and educational meetings to discuss emergency planning.

4. Encourage the use of written procedures.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the following:

· Scott County Health Department for their support for this study. My great mentor Doug Saunders for his patience and experience. Finally, to all of Cohort X for their support, professional insights, and for making participation in the Fellowship a great experience.

References

Clark, M. (2021, January 1). 2020 in the quad Cities: Derecho’s impact still felt nearly five months later. TV 6 News KWQC. 2020 in the Quad Cities: Derecho’s impact still felt nearly five months later. KWQC:https://www.kwqc.com/2021/01/02/2020-in-the-quad-cities-derechos-impact-still-felt-nearly-five-months-later/

Committee, 2. C. (2012-2014). Emergency action plan for retail food establishments. Orlando, Florida: 2014 Conference for Food Protection.

Corfidi, S. F., Evans, J. S., & Johns, R. H. (2022, January 11). NOAA-NWS-NCEP Storm Prediction Center. About derechos. https://www.spc.noaa.gov/misc/AbtDerechos/derechofacts.htm#whatsnew

Marx, M. A., Rodriguez, C. V., Greenko, J., Das, D., Heffernan, R., Karpati, A. M., Mostashari, F., Balter, S., Layton, M., & Weiss, D. (2006). Diarrheal illness detected through syndromic surveillance after a massive power outage: New York City, August 2003. American Journal of Public Health, 96(3), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.061358

Watson, J. T., Gayer, M., & Connolly, M. A. (2007). Epidemics after natural disasters. Emerging infectious diseases, 13(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1301.060779

Wolf, R. (2020). Midwest Derecho 2020: Understanding the Science and impacts. National Weather Service. Ames: National Integrated Drought Information System.

Author Note

Logan Hildebrant, Environmental Health Specialist

Scott County Health Department

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort X.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to:

Logan Hildebrant, Scott County Health Department,

600 W. 4th St. Davenport, IA 52801

Logan.hildebrant@scottcountyiowa.gov

Funding for the IFPTI Fellowship in Food Protection Program was made possible by the Association of Food and Drug Officials.