Pathogen Contamination of Produce and Its Effects on Military Procurement

Mekisha Cunningham

Deputy Director, Field Operations

Food Analysis and Diagnostic Laboratory (FADL)

Abstract

Fresh fruits and vegetables are high in nutritional value to the human diet; however, contaminated produce has been the subject of multistate foodborne outbreak investigations. These outbreaks raise questions on food safety and place a spotlight on the practices of the agricultural industry. Produce contamination may occur at any point from farm-to-table, and has become a major threat to food safety. The Produce Safety Rule was established to address these concerns. This research paper studies how produce contamination affects procurement for the Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA). Insights identified are general requirements for procurement, how pathogen control requirements for produce may or may not differ between suppliers, and what impacts were noticed due to pathogen contamination of produce.

Key words: Outbreaks, contamination, produce

Pathogen Contamination of Produce and Its Effects on Military Procurement

Background

The Produce Safety Rule is part of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Safety Modernization Act signed into law by President Obama on January 4, 2011. The Produce Safety Rule was available publicly on November 13, 2015 and published in the Federal Register on November 27, 2015. The rule established science-based minimum standards for the safe growing, harvesting, packing, and holding of fruits and vegetables for human consumption. Standards found within Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations part 112 were developed in an effort to prevent microbial contamination and reduce foodborne illnesses, yet pathogen contamination of produce continues to create a heightened sense of urgency to pinpoint root cause and specific measures to prevent such contamination.

For many years, foodborne pathogen contaminations were commonly associated with ground beef, poultry products, meats, eggs, dairy, products with dairy, soft cheeses, and other processed foods. However, in recent years, microbiological foodborne outbreaks associated with fresh fruits and vegetables (FF&V) have increased since FF&V often are consumed in their raw state with no processing step to eliminate pathogens (Carstense, et al., 2019). Salmonella spp, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacter spp. and Listeria monocytogenes are the most common pathogens that contaminate fresh produce (Wadamori, et al. 2016). All people are susceptible, however young children and the elderly are more susceptible and at higher risk for illness to progress to more severe complications. People with weakened immune systems also are at risk.

Department of Defense Directive 6400.04E designates the Secretary of the Army as the Department of Defense (DOD) Executive Agent for DOD Veterinary Public and Animal Health services. The U.S. Army Veterinary Corps provides food safety and security inspections for the United States Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. Air Force Public Health is responsible for food safety on Air Force bases. The DOD Food Protection Program encompasses the gamut of food safety and defense activities, such as the Commercial Food Protection Audit program, and the Surveillance Food Laboratory and Destination Monitoring program. The Commercial Food Protection Audit program is a critical step in ensuring the receipt of safe, wholesome food for military procurement. Manufacturers must prove evaluation of the process conducted for food safety by a recognized food safety or public health agency, and meet the standards for food safety. Surveillance Food Laboratory and Destination Food Monitoring programs provide surveillance capability for food by identifying high-risk items, then making recommendations on which products to submit for microbiological testing while in a field environment or at-home station.

While the Produce Safety Rule and DOD Food Protection Program are crucial to food safety, produce contamination continues to increase. One thousand seven hundred seventy-nine (1,779) foodborne outbreaks with a confirmed food vehicle and cause occurred in the U.S. from 2004 to 2010, of which 9.2% (163) were attributed to fresh produce (CDC, 2017). From 2010 to 2017, 1,797 foodborne outbreaks with a confirmed food vehicle and cause occurred in the U.S., of which 12.7% (228) were attributed to fresh produce (CDC, 2017). Commissaries serve as the only grocery store for a military installation. Produce is a small but important section within DeCA commissaries. DeCA, headquartered in Fort Lee, VA, operates a worldwide system of 260 commissaries (Defense Commissary Agency, 2022). These commissaries sell food and related household items to active, reserve, and guard members of the U.S. military forces; retirees of these services; authorized family members; and other authorized patrons.

Army Regulation 40-657 of the Veterinary/Medical Food Safety, Quality Assurance, and Laboratory Service, states commercial food establishments and distributors are subject to sanitation approval and surveillance as deemed necessary. The Armed Forces procures foods only from the Worldwide Directory listing or locally approved establishments domestically and overseas. DOD may grant a waiver if domestic firms do not make or produce the product, such as some produce imported to the U.S. like bananas, mangoes, apples, asparagus, garlic and eggplant.

With 260 commissaries worldwide, DeCA was a prime candidate for this research project. The commissary benefit—as the grocery leader for the military—is a much-prized part of the military community. The commissary vision is to be the best grocery provider of choice for eligible patrons (Defense Commissary Agency, 2022). Providing the best FF&V is a high standard DeCA intends to meet for all customers—overseas and at home. In light of the continuing challenges with contamination of produce, and the importance of procurement of safe food for a strong military, this research sought information on the impact of produce contamination on military procurement.

Problem Statement

The impact of pathogen contamination of fresh fruits and vegetables (FF&V) on military procurement is unclear.

Research Questions

What are the general requirements for procurement of FF&V for U.S. Armed Forces?

Are there differing pathogen control requirements applied to nationwide/regional commercial suppliers of FF&V as opposed to the requirement applied to local producers/supplier of FF&V within the U.S.?

Did procurement of FF&V change due to pathogen contamination, and if so, how?

Methodology

A survey developed with Microsoft Word was electronically distributed to 75 commissaries. Respondents included a combination of produce managers, merchandisers, consumer safety officers, and contracting personnel. The survey used closed-ended questions, with space for comments, to assess general requirements for FF&V procurement, pathogen control requirements, and the impact of produce contamination within DeCA operations. Information was used to analyze procurement knowledge, differences in pathogen control requirements for suppliers of produce, and impacts of pathogen contamination.

Results

Eighty-nine (89) survey responses were received. The survey determined 100% of respondents use DeCA’s Technical Data Sheet for FF&V. This document is used to ensure suppliers/contractors comply with DeCA’s requirements for the receipt of FF&V. The document outlines the general requirements, quality assurance provisions, and nonconforming supplies and packaging/packing/labeling/marking for FF&V.

The supplier/contractor must notify DeCA’s contracting office of a voluntary recall or withdrawal of any FF&V from the market. Delivery temperature of vehicles transporting FF&V is between 34°F and 40°F, or as otherwise stated by the contractor. DeCA commissaries shall receive quality FF&V that meet, or exceed U.S. Grade No. 1. This grade represents the highest-quality goods, for example: good texture; fresh smell; uniformity of size/shape; and is the chief grade for most fruits and vegetables.

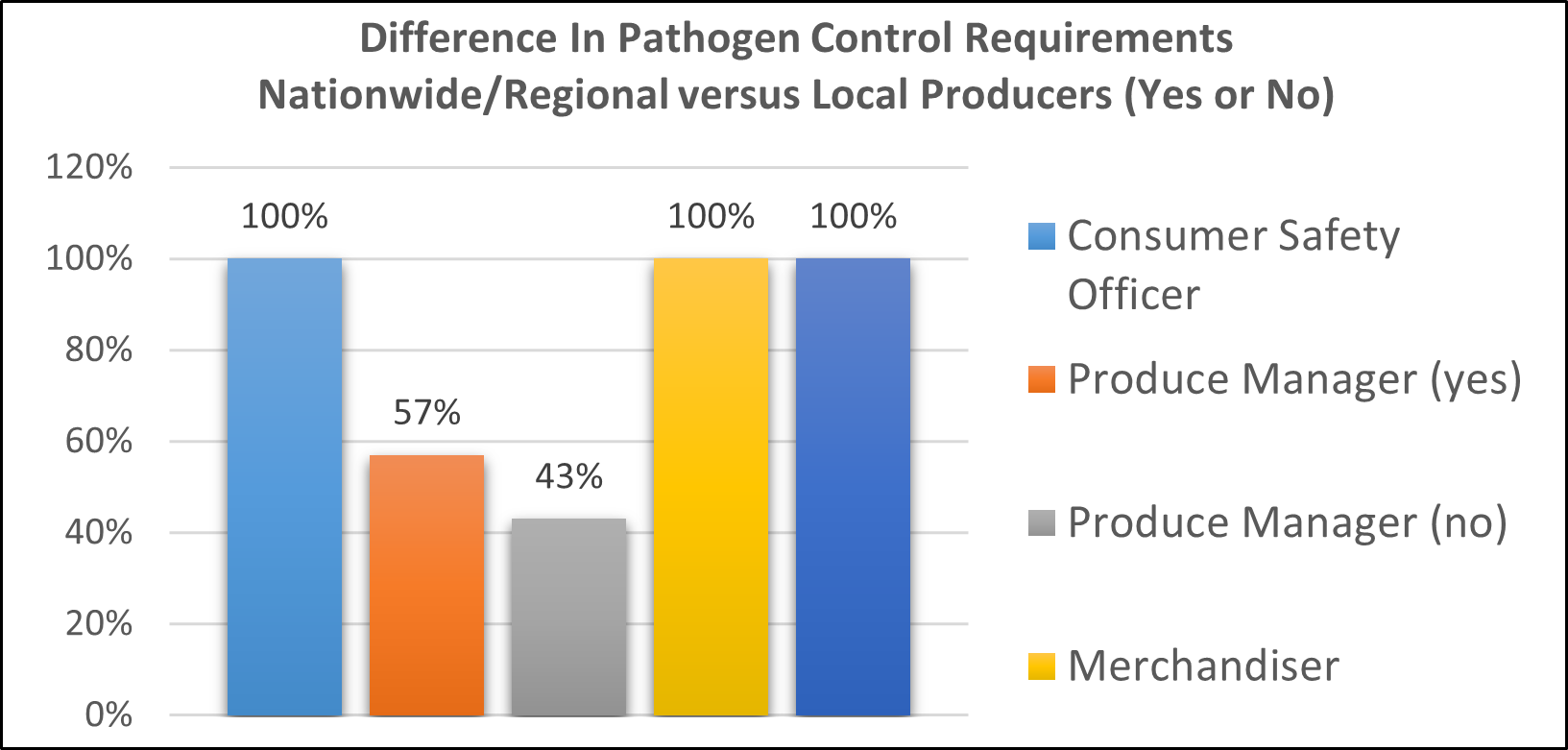

Graph 1 below gives a breakdown by percentage by respondents regarding pathogen control requirements between nationwide/regional versus local suppliers of FF&V. Consumer safety officers, merchandisers and contracting respondents each report 100% differences in control between nationwide/regional and local producers. Produce managers see a difference in pathogen between nationwide/regional and local producers, reporting 57% yes and 43% no, respectively.

Graph 1

Difference In Pathogen Control Requirements Nationwide/Regional versus Local Producers (Yes or No)

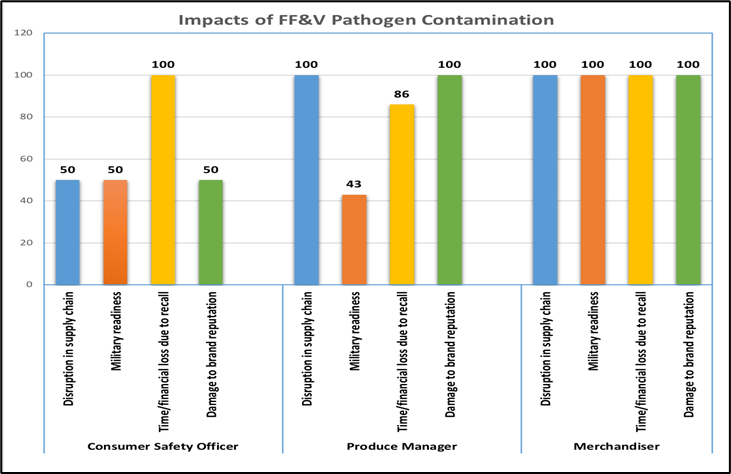

Impacts of pathogen contamination of FF&V are displayed on Graph 2, below. Disruption in the supply chain, potential impact on military readiness, time and financial loss due to recalls and damage to brand reputation were the top selections chosen on the survey. Of all the respondents, contracting personnel reported no impacts noticeable to DoD procurement of FF&V due to pathogen contamination. Fifty percent of consumer safety officers believe FF&V pathogen contamination causes disruption in supply chain, military readiness and damage to brand reputation; 100% of consumer safety officer believe pathogen contamination impact time/financial loss due to recalls. One hundred percent of produce managers believe FF&V pathogen contamination impacts damage to brand reputation and causes disruption in the supply chain while 43% believe contamination impacts military readiness and 86% believe contamination impacts time/financial loss due to recalls. One hundred percent of all merchandisers believe pathogen contamination impact all four categories listed.

Graph 2

Impacts of Pathogen Contamination

Conclusions

This research led to the following conclusions:

1. All survey respondents indicated compliance with the technical data sheet for FF&V, ensuring the receipt of safe and wholesome FF&V to DeCA facilities.

2. Respondents’ beliefs that pathogen controls are different between nationwide/regional, versus local producers, may be based on processed versus unprocessed, raw FF&V.

3. Pathogen contamination of FF&V has a negative effect on procurement. Time and financial loss due to recall cause significant economic issues for FF&V producers. Media coverage and social media help spread the news of recalls, creating panic amongst buyers which may cause a disruption in supply chain if time is needed to contract with additional vendors.

Recommendations

This research led to the following recommendations:

1. Perform a second survey with a focus on Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) Troop Support Subsistence supply chain. The DLA Subsistence supply chain provides food for military all over the world; from dining facilities on military installations to a ship’s kitchen. The study will provide new data on how pathogen contamination affects military procurement of FF&V for troop-feeding facilities.

2. Military personnel do not inspect farms and must rely on FDA and FSMA requirements to ensure FF&V safety. Military personnel should conduct joint inspections with delegated agencies when mission permits. Personnel can observe how federal agencies inspect suppliers of FF&V at point of origin, and what each supplier does to meet USDA/FDA standards and general requirements for military procurement for DeCA facilities.

3. A more thorough review of where time and finances are lost should be performed to determine if there is a correlation with military readiness.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the following:

· God for the blessing of selection as a fellow for Cohort X.

· My husband, Dewayne, daughter Gabrielle and best friend, Tamera McClure, for their unwavering support during this entire process. Thank you for standing beside me as I evolve into a better leader.

· IFPTI mentors Doug Saunders and Kathy Fedder. Your mentorship and guidance during this fellowship was priceless.

· IFPTI staff for their role in helping make this fellowship a success.

· Cohort X for your support but in particular your friendship. You all made this fellowship worthwhile.

· FADL Director, Colonel (COL) Michelle Thompson and Army Public Health Command Director COL Alisa Wilma for supporting my decision to participate in the IFPTI fellowship program.

· FADL teammates for believing I could get the job done.

· Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Angela Schmillen, Director of Health and Safety, DeCA Headquarters, Fort Lee, VA and her team of experts for participating in the survey

· Brenda Morris, Director of Produce Safety, Association of Food and Drug Officials, York, PA.

· Dr. Ernie Julian, Co-chair, Healthy People 2030 Foodborne Illness Reduction Committee, Co-chair Healthy People 2030 Produce Workgroup, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Brown University.

· Thomas P. Saunders, Southeast Regional Extension Associate, based in Richmond, VA, Produce Safety Alliance, Cornell Agritech, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Agricultural Sciences Research Laboratory.

References

Carstens, C.K., Salazar, J.K. & Darkoh, C. (2019). Multistate outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United States associated with fresh produce from 2010 to 2017. Front. Microbiol. 10:2667. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02667

Wadamori, Y., Gooneratne, R., & Hussain, M. A. (2017). Outbreaks and factors influencing microbiological contamination of fresh produce. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 97(5), 1396–1403. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.8125.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/norsdashboard/.

Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA). https://www.commissaries.com/

Produce Safety Rule.https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-final-rule-produce-safety

Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations Part 112. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-112

Author Note

Mekisha Cunningham, Deputy Director, Field Operations

Food Analysis and Diagnostic Laboratory (FADL)

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort X.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to:

Mekisha Cunningham, Food Analysis and Diagnostic Laboratory

2899 Schofield Road, Suite 2630, Joint Base San Antonio,

Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234

Mekisha.w.cunningham.mil@mail.mil

Funding for the IFPTI Fellowship in Food Protection Program was made possible by the Association of Food and Drug Officials.