Comparison of Priority Violations in Restaurants Inspected by State and Local Inspectors

Nicole Kragness

Regulation and Licensing Division Manager, Eau Claire City-County Health Department

Abstract

Restaurants in Wisconsin are regularly inspected, one time per year, by local and state inspectors, but limited analysis has been conducted on inspection data regarding the number and type of violations that are cited during a routine inspection. Data from the 2018-19 license year, compiled from an electronic inspection database, Healthspace, was analyzed to determine if there was a statistical difference between violations written by a local versus a state inspector in a complex restaurant. State inspectors wrote an average of 7.0 priority violations per inspection, compared to 4.7 priority violations written by a local inspector during a routine inspection. State and local inspectors most frequently wrote core violations, whereas state inspectors wrote priority violations at a slightly higher rate than local inspectors (28% and 25% respectively). Standardized state inspectors were interviewed on the findings and the variety of factors that may influence the number of violations written. The statistical difference between the number of violations demonstrates the need for further collaborative training opportunities between state and local inspectors in Wisconsin.

Key words: priority violations, Healthspace, complex, Wisconsin, local

Comparison of Priority Violations in Restaurants Inspected by State and Local Inspectors

Background

In 2017, restaurant facilities were implicated in 64% of reported foodborne illnesses in the United States. Compared to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Summary Report from 2009-2015, these numbers show a slight increase in which restaurants were implicated in 61% of foodborne illness outbreaks. At the state level, Wisconsin reported 10 foodborne illness outbreaks to the National Environmental Assessment Reporting System (NEARS) in 2018. Complex restaurants were implicated in 70% of these outbreaks (NEARS Report 2018, DATCP). A complex facility is one that cooks, cools, processes, and provides seating and meals for 75 or more people, per day, which may increase the likelihood for foodborne illnesses to occur in the facility. Eighty percent of complex restaurants with a reported outbreak had at least one critical violation in their routine inspection during the 2018-19 license year. In 2019, 18 foodborne outbreaks were reported to NEARS, and 83% of those occurred from complex restaurants. A full 75% of implicated establishments had at least one critical violation on their inspection report from the 2018-2019 license year. (NEARS Report 2019, DATCP)

Wisconsin has 72 counties. Per Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection (DATCP) requirements in WI ATCP 72, 73, 75 and Appendix 76, 78, 79, “each county must conduct one routine inspection, of each licensed restaurant, per license year, under its jurisdiction.” Wisconsin restaurant licenses are valid from July 1 of a year to June 30 of the following year. In Wisconsin, some restaurants see a local inspector, while others have a state inspector from DATCP. Of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, 22 are inspected by DATCP or state inspectors. The remainder are inspected by local or tribal agencies.

For the purpose of this research, a “local inspector” is one in which a county inspector from a public health department conducts inspections, and a “DATCP inspected county” is one in which a state inspector conducts inspections. Each of these Wisconsin counties also may be categorized into one of four geographic regions, as defined by the Wisconsin Environmental Health Association. These are categorized by Northwest, Southwest, Northeast, and Southeast, noted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

WEHA Districts

Source: WI Environmental Health Assoc.

Because inspection practices may vary across jurisdictions, Wisconsin utilizes FDA Standardization of retail food inspection personnel. Every three years, each local county is required to complete a DATCP evaluation. This evaluation includes an assessment of documented training programs for local inspectors to complete independent inspections. Additionally, each year DATCP completes standardization with at least one representative from each local county to demonstrate proficiency and apply Wisconsin Food Code provisions to a uniform system of measurement. Each local county is required to have one standardized inspector, who then standardizes the rest of the local staff sanitarians to ensure inspections are uniform across the state when conducting inspections and writing reports.

Wisconsin restaurants are categorized and licensed by evaluating the complexity of restaurant activities performed. During the license year reviewed for this study (2018-19), Wisconsin used a points system to determine the complexity of a food establishment.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the most recent and complete data set is the 2018-19 license year. Between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, 24,850 total food establishment inspections were conducted in Wisconsin (Healthspace Wisconsin Database). Of those, 16,455 inspections were marked as routine inspections (66%, Figure 2). In the studied license year, 10,036 violations were written at complex food facilities.

Figure 2

2018-19 Wisconsin Food Inspections by Type

Wisconsin conducts risk-based inspections established by the FDA Risk Based Inspection Model. When violations are written, they are categorized in three different groups, per the Wisconsin Food Code:

1. “Priority Item: A provision whose application contributes directly to the elimination, prevention, or reduction to an acceptable level, hazards associated with foodborne illness or injury, and there is no other provision that directly controls the hazard.” Previously called “critical violations,” these are more likely than other violations to contribute to foodborne illnesses if not corrected. These violations are items with a “quantifiable measure to show control of hazards,” such as cooking, reheating, cooling, and handwashing.

2. Priority Foundation Item: A provision whose application supports, facilities, or enables one or more priority items.

3. Core Item: A provision that is not a priority or priority foundation item and usually relates to general sanitation, operational control, sanitation standard operating procedures, facilities or structures, equipment design, or general maintenance.

Although there is a standardization program in place, there is an opportunity to assess how state and local inspections compare by evaluating available information in the Wisconsin Healthspace database. The results of this analysis could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the current standardization program and provide potential improvements in training among state and local inspectors.

Problem Statement

A comparison of violations cited by DATCP vs local inspectors in complex restaurants in Wisconsin has not been conducted.

Research Questions

1. What were the average number of violations cited, during a routine inspection of a complex facility, by a local inspector vs DATCP inspector during the 2018-19 license year?

2. What type of violation was most frequently written during a routine inspection of a complex food facility in the 2018-19 license year?

3. Is there a statistical difference between the types of violations written by DATCP and local inspectors?

4. Is there a statistical difference between violations written in different geographical locations in Wisconsin?

5. What are the perceptions of experienced Wisconsin DATCP standardized inspectors regarding the methodology and findings of this study?

Methodology

For this retrospective review of inspections, the 2018-19 license year was selected because many counties paused routine inspections to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic during the 2019-20 license year. Electronic data collection was compiled from Healthspace, an electronic inspection program that is utilized by counties in Wisconsin to complete inspection documentation. This program allows Wisconsin users to download data by county, and sort by many different data sets including types of establishments, inspections, complexity, and violation type. Using the Wisconsin Healthspace Inspections and Violations Report builder, the following parameters were chosen and repeated for each county:

· Date: 07/01/2018 to 06/30/2019; All Databases

· Facility County: County name to analyze;

· All Cities, All Regions, Health Department Name or DATCP;

· Module: Food;

· Facility Type: Restaurant, Retail Food-Serving Meals;

· Billing Type: High Complexity, Complex;

· Stage: Active; Administrative Status: Active; License Status, Active;

· Inspection Type: Routine.

To standardize data and account for differences in the number of complex establishments per county, the following data points were used: number of routine inspections; number of violations; and type of violations documented during routine inspections in both local and DATCP inspected counties. Additionally, the most frequently written priority violation and frequency of this occurrence was analyzed for each county.

Four counties were omitted from this study because they did not utilize Healthspace or did not have any complex facilities. The data was separated into two groups: DATCP and local. Data points analyzed for each group include:

· Average violations per inspection;

· Percentage of priority violations written;

· Percentage of priority foundation violations written; and

· Percentage of core violations written.

Using Microsoft Excel, a p-value and ANOVA statistical calculation was used to determine if there was a statistical difference between these groups. After analyzing results, two separate semi-structured interviews were conducted with two experienced DATCP FDA standardized inspectors. Questions asked included perceptions of the results and research methods, additional training opportunities between DATCP and local counties, and future implications for standardization for food safety in Wisconsin.

Results

During the 2018-19 license year, DATCP inspectors wrote an average of 7.0 violations per inspection at a complex facility, whereas local inspectors wrote an average of 4.7 violations per inspection (Figure 3). These were statistically different (p=0.050).

Figure 3

Average Violations per Routine Inspection 2018-19

When comparing the type of violations written between local and DATCP inspectors, there was no statistical difference between the two groups. Local and DATCP inspectors most frequently write core violations (53%, 47% respectively) (Figure 2, Figure 3). DATCP inspectors wrote more priority and priority foundation violations during a routine inspection than local inspectors (28%, 25% respectively). (Figure 4, Figure 5).

Figure 4

Type of Violation Written by Local Inspector 2018-19

Figure 5

Type of Violation Written by State Inspector 2018-19

The most frequently written priority violation by a local inspector was cold holding, whereas the most frequently cited priority violation during a DATCP inspection was cross contamination: raw over ready to eat foods.

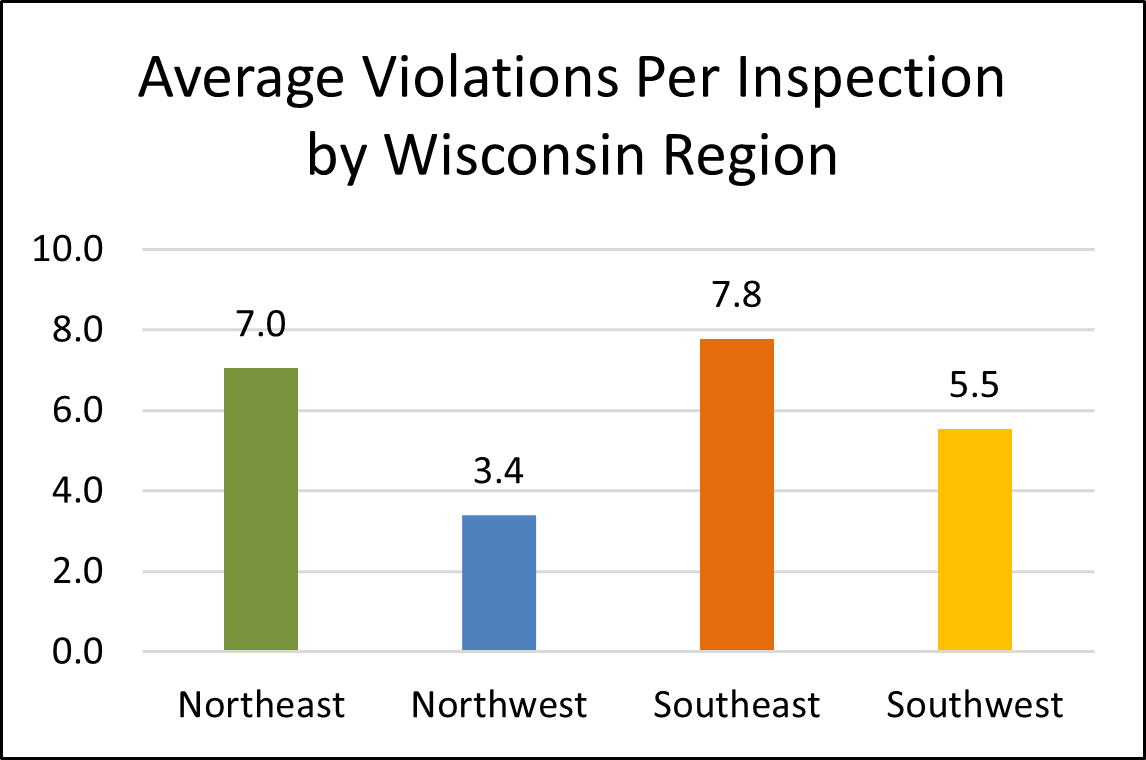

Further organizing the local inspection data into four Wisconsin geographic regions (as categorized by Wisconsin Environmental Health Association) shows the Northwest Region wrote the least number of violations per inspection, compared to the rest of the state and is statistically significant (p=.0005). (Figure 6). The Northwest Region is comprised of the most counties in a region (Figure 7). Compared to other WEHA regions in Wisconsin, the Northwest Region has the most counties in the district and highest percentage of local inspectors (28 counties, 78% local inspectors).

Figure 6

Average Violations per Routine Inspection by WEHA Region

Figure 7

Number of Counties Per WEHA Region

Discussions with experienced DATCP inspectors showed some surprise at the findings of the data, as well as recommendations on how these results could be used to benefit the food inspection program in Wisconsin. DATCP inspectors also suggested the differences in the number of violations may be due to a time gap of more than one year between inspections of facilities, and the years of field experience inspectors possessed.

Conclusions

Results indicated a significant difference between the number of priority violations written in locally inspected versus DATCP inspected facilities. Discussions with DATCP inspectors indicate there may be underlying factors that influence the number of violations that Wisconsin inspectors write during routine inspections. These factors may include (but are not limited to): years of experience of field inspectors; quality and amount of training received by inspection staff; time of day the inspection was conducted; processes occurring within the facility; knowledge of person in charge; and the overall condition of the facility. Additionally, there may be discrepancies between violation marking practices. Priority violations may be verbally addressed during routine inspections and undocumented to limit the need for a follow-up inspection, based on limited workforce capacity.

While the types of violations are the same across the two groups, the number of violations written is statistically different. Results indicated a significant difference between the number of priority violations written among geographic areas of Wisconsin. The Northwest region inspectors wrote the lowest number of violations during a routine inspection, whereas the Southeast region inspectors wrote the highest number of violations during a routine inspection.

Recommendations

A systematic and ongoing assessment of Wisconsin inspection reports written by both local and DATCP inspectors should be incorporated into a state food safety program review each license year. Significant differences between local and DATCP programs may indicate a need for increased field training and standardization may be necessary for local inspectors, including risk-based inspection training. Another comparative assessment should occur after the 2021-22 license year to identify trends and determine the most effective approach and intervention. Additionally, as inspectors move back to routine inspections following the COVID-19 pandemic, there may be a need for a review of standardized inspection practices or additional shadowing field training from DATCP for local food inspection staff.

At the local level, each county could use these results to tailor outreach to operators based on the most common violations seen in their county. For example, a county that most frequently writes a cold holding violation may focus its education efforts on this risk factor during routine inspections. Frequent priority violations may provide an opportunity to educate local operators on how best to utilize cooler logs, calibrate thermometers, and promote active managerial control of their facility.

Violation trends in future data may enhance information sharing at regional food safety meetings. This information sharing may facilitate open communication and improved relationships between DATCP and local inspectors. Furthermore, analyzing the types and frequency of priority violations may show the need for Wisconsin Food Code changes, new statewide policies, and the creation of additional training programs or shadowing opportunities between experienced and less-experienced inspectors.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge IFPTI for awarding me this opportunity to focus on food safety research in Wisconsin, as well as the other Fellows in Cohort X for enhancing this experience and providing feedback and support. I would also like to thank DATCP staff Carrie Pohjola and Reed McRoberts for their assistance and guidance. Lastly, I would like to thank my previous organization, La Crosse County Health Department, as well as my current employer, Eau Claire City-County Health Department and my manager Carol Drury for the support and encouragement.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Environmental Assessment Reporting System (NEARS). (2018). 2017 Summary Report Wisconsin (pp. 1–2).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for

foodborne disease outbreaks, United States, 2017, Annual Report. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019.

Dewey-Mattia, D., Manikonda, K., Hall, A.J., Wise, M.E., & Crowe, S.J. Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 2009–2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 2018;67(No. SS-10):1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6710a1.

Wisconsin Environmental Health Association. https://weha.net/.

Author Note

Nicole Kragness, Registered Sanitarian

Eau Claire City – County Health Department

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort X.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to:

Nicole Kragness, Eau Claire City-County Health Department, 720 2nd Ave,

Eau Claire, WI 54703

Nicole.kragness@co.eau-claire.wi.us

Funding for the IFPTI Fellowship in Food Protection Program was made possible by the Association of Food and Drug Officials.