Behavior Change Inspection Model: A Tool for Improving Food Safety

Sarah Robbin, MS, REHS

Lead Registered Environmental Health Specialist

El Paso County Public Health

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2012 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

This study explored the impact of a behavior change inspectional model adopted from the Health Belief Model (HBM) on food safety at the retail level in El Paso County, Colorado (EPC). The study focused on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Risk Factor Violations (RFVs) cited during routine regulatory inspections. The RFVs, determined by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and adopted by the FDA, identify conditions known to cause foodborne illnesses. To observe the impact of this behavior change model, inspection data and foodborne illness outbreak data from EPC was collected and analyzed prior to and following the implementation of the behavior change inspection model. Additionally, input from EPC food safety specialists was collected and analyzed along with inspection routine time data. The study found a reduction in the frequency of reported FDA RFVs during routine inspections, a reduction in the incidence of food borne illness outbreaks, and a slight decrease in the time inspectors spent in a facility during routine inspections after implementation of the behavior change model.

Background

The goal of all regulatory inspections is compliance with food safety regulations. Long-term compliance in a retail food facility indicates that a facility is serving safe food. If a facility cannot achieve compliance, a food safety specialist must perform numerous follow-up inspections that can lead to warning letters, letters of non-compliance, monetary civil penalties, hearings, and license/permit revocation proceedings. These methods are collectively known as enforcement and may not necessarily lead to long-term compliance. Monetary civil penalties, which may come about during enforcement, may adversely impact relationships and may discourage future compliance with food safety regulations (Verlee 2012).

The more serious food safety violations are labeled as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Foodborne Illness Risk Factor Violations (RFVs). FDA RFVs are conditions known to lead to foodborne illness (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2006). Examples of FDA RFVs include using food from unapproved sources, cross contamination between raw animal products and ready-to-eat foods, lack of adequate hand washing (facilities and the act of), poor personal hygiene, employees working while they are ill with norovirus, bare hand contact with ready-to-eat foods, smoking/eating/drinking in food preparation areas, food temperature violations (holding temperatures as well as cooling and reheating), lack of an approved water source, and lack of proper sewage disposal.

A Colorado State Task Force has outlined “winnable battles” for the state; one of those battles centers on providing safe food for the citizens of Colorado. For the calendar year of 2011, 14.3% of all regular retail food inspections in Colorado cited three or more of the FDA RFVs (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, 2011). The goal by 2016 is to decrease by 5% the number of inspection reports with three or more FDA RFVs cited. The question for achieving this goal is: what strategy or strategies can food safety regulatory agencies employ to reduce the prevalence of risk factor violative conditions in retail establishments?

To help state and local agencies improve their retail food programs, the FDA has introduced the Voluntary National Retail Food Regulatory Program Standards. One of the anticipated goals of implementing the Standards is a reduction of the FDA RFVs cited during regular inspections (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2009). The Standards require departments to complete a self-assessment of ten different areas within their program, identify the gaps, and work toward filling in the gaps. A combination of three of these self-assessment areas (staff training and competency, industry outreach, and inspectional reviews) may help achieve the goal of reducing the prevalence of risk factor violative conditions in retail establishments.

In June 2011, along with traditional enforcement methods, the El Paso County Public Health Environmental Health Division (EPC) implemented a behavior change model for inspections. The behavior change model was implemented to address new challenges and continual non-compliance with the FDA RFVs by retail facilities. An additional issue that needed to be addressed was the lack of communication EPC had with the local industry and the other specialists.

The behavior change model employed by the EPC stems from the Health Belief Model (HBM) first introduced in the 1950s by social psychologists Hochbaum, Rosenstock, and Kegels (Glanz, Rimer, Lewis 2002, and T. Gonzales, personal communication, September 2012). The concept posits that a person will perform the necessary healthful actions if he or she believes that a negative health condition may be avoided by taking a recommended action (T. Gonzales, personal communication, September 2012). The application of the EPC model focused on the way inspections are performed.

The goal of the EPC model is to increase compliance with food safety regulations and thereby increase the safety of food being served in the retail food facilities. In this model, food safety specialists work with the owners and operators in a proactive partnership to ensure safe food is being served. The specialists conduct inspections to assess compliance with food safety regulations, note any violations, and discuss the necessity of corrective action with the owner and/or operator. The specialists explain possible outcomes of not correcting the violation, and discuss how the owner and/or operator may be able to correct the violation. Food safety specialists can provide guidance; however, they cannot specify how a violation must be corrected. After conferring with the owner and/or operator, specialists either schedule a follow-up inspection or ask for documentation to be sent to the inspector describing how the violation was corrected.

As an industry outreach strategy, EPC developed a series of colorful, one-topic handouts to aid facilities with violation corrections and remind staff how to serve safe food. Monthly staff meetings were used to discuss inspectional reviews and conduct in-service training on proper marking of the FDA RFVs, striving for consistency among specialists.

Environmental health specialists may be involved in multiple programs such as food safety, septic systems, drinking water, pools, air quality, body art, and school safety. The workload of each of these programs requires a certain number of inspections to be accomplished each day. For example, for food safety, Colorado requires two regular inspections per facility per calendar year (Colorado Retail Food Establishment Rules and Regulations, 2006). In EPC, this requirement equates to approximately 5,000 inspections a year, or approximately 19 inspections per day by the 14 EPC food safety specialists, for food facilities. A potential benefit of the EPC model is the need for fewer follow-up inspections, which may allow inspectors to meet the workload.

Problem Statement

Regulatory agencies strive for long-term compliance with food safety regulations through the use of routine regulatory inspections. A behavior change model was implemented in El Paso County, Colorado to reduce the prevalence of violative food safety conditions in food establishments; however, no data exists regarding the impact of this model.

Research Questions

1. How did the implementation of the behavior change inspection model impact the prevalence of the FDA RFVs noted during routine regulatory inspections?

2. What is the correlation between foodborne illness outbreaks and the implementation of the behavior change inspection model?

3. How did the implementation of the behavior change inspection model impact the time spent in a food service facility?

Methodology

To address question number one (1), routine inspectional violation data was gathered for 15 months before and 15 months after implementation of the model by EPC using the Garrison Software System (an environmental health data management system used by EPC) and EPC’s data analyst Christopher Wright. The data was analyzed for FDA RFVs cited per routine inspection. Quarterly averages occurring before and after implementation of the behavior change inspection model were graphed and averaged over all inspections. Statistical analysis was performed to determine significance between the averages.

To address question number two (2), foodborne illness outbreak data was gathered using the El Paso County Public Health Communicable Disease Division Database. The same time frame was utilized along with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definition of outbreak: defined as two or more people getting the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink. The outbreaks were graphed showing the number of incidences before and after implementation of the behavior change inspection model.

To address question number (3), data regarding the amount of time inspectors spent conducting inspections was manually gathered through a random sampling of inspectional time stamps. The Garrison Software System was used to analyze the time data from inspection reports from the time frame of 15 months before and 15 months after implementation of the behavior change model. One hundred facilities were chosen at random, from the group of facilities that had routine inspections before and after implementation of the behavior change model, and whose inspection reports contained time data. The data was analyzed and graphed. .Additionally, a 5-item survey was developed and sent to food safety specialists within EPC to gather time and violation information. This information was compared with the data base results.

Results

Data analysis of the routine inspectional violations revealed an average of less than one FDA RFV citation (.794 or 79 citations within 100 inspection reports) per inspection within El Paso County, Colorado, prior to the implementation of the behavior change model. Figure 1 displays the average number of FDA RFVs per inspection (out of 100) per quarter over the 15 months prior to, and after the implementation of the behavior change model, as well as the average number of FDA RFVs over each time period. The average number of inspections with one or more FDA RFVs shows a decrease from approximately 79 per 100 inspections prior to implementing the behavior change model to approximately 64 per 100 inspections after implementation.

A two-tailed t-test was conducted on the monthly average number of FDA RFVs per regular inspection to see if the difference was significant. The p-value was 0.00399 for these two data sets; a p-value of less than 0.05 is significant. The reduction in number of times FDA RFVs were cited is statistically significant.

The number of foodborne illness outbreaks within El Paso County, Colorado also shows a decline. A total of 10 outbreaks occurred before implementing the behavior change model. After the implementation, 4 outbreaks occurred in a similar time frame (Figure 2). A two-tailed t-test was conducted on the number of outbreaks to see if the difference was significant. The p-value was 0.12688 for these two data sets, and not significant.

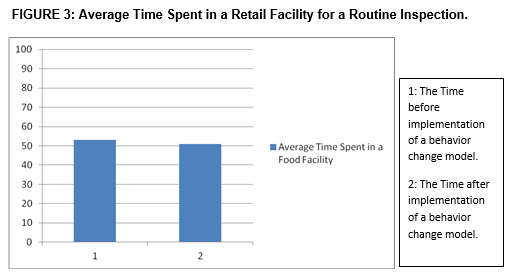

Analysis of the amount of time spent performing routine inspections revealed a change from an average of 53 to 50.82 minutes, an average of a 2.18 minute difference (Figure 3). Two minutes is not statistically significant (p-value= 0.559). Food Safety Specialists did not perceive that there was an increase in time spent in a facility and the data gathered confirms this.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that there may be real value in using the Health Belief Model in the form of a behavior change model for the EPC retail food inspection program. After EPC implemented a behavior change model there were fewer FDA RFVs cited per routine inspection within the 15 months after implementation, as compared to the same time period prior to implementation. Within the same time period, EPC had fewer reported foodborne illness outbreaks. However, implementation of the behavior change model did not significantly decrease the amount of time a specialist spent in a facility. The lack of a time change may be due to the specialist spending more time focusing on the FDA RFVs and educating the operators on the importance of correcting and keeping these violations corrected (El Paso County Specialists, personal communication, October 2012).

Recommendations

Based on the results of this study, state and local departments with a retail food inspection program should consider adopting the Health Belief Model, and implementing a behavior change model for routine inspections. Implementation of a behavior change inspection model could shift the focus of a routine inspection to the FDA RFVs and educating the owner and/or operator on the possible outcomes of not correcting violations. Food safety specialists should have meetings (once or twice a month) to discuss trends of violations and to focus on consistency in citing violations. Lastly, a high level of importance should be placed on having handouts for operators to convey basic food safety concepts. The handouts should be easy to read, convey only one topic, and be colorful to attract attention. The handouts should be in the major languages of the jurisdiction. Departments that currently have materials should share those materials and other successful program elements to help other departments achieve successful results.

Future areas for study should focus on whether implementing a behavior change inspection model results in fewer follow-up inspections and fewer compliance activities. Another area of future study would be to see if the trend in reduction of FDA RFVs cited continues over the next 3 to 5 years or levels off. Lastly, a relationship between high turnover in management and violations, regardless of how much time a specialist spends on educating the operator, may exist and may require further study.

Acknowledgements

I want to extend my sincere thanks to Dan Sowards, my IFPTI Fellowship mentor, without whom I could not have accomplished this project. I wish to also thank all the staff and subject matter experts at IFPTI, as this has been a truly unforgettable experience. To my cohort fellows, I could not have picked a better, more unique, fun group. I know I have made lifelong friends and will cherish you all. I must thank my department, El Paso County Public Health, Jill Law, Tom Gonzales, Mike McCarthy, Jim Goodwin, Christopher Wright, and Lynnea Rappold for their support in this endeavor. Lastly, I must give credit to my wonderful husband, Dave, who is my rock and never doubts my abilities.

References

Colorado Retail Food Establishment Rules and Regulations. (May, 2006). Section 11-201 A.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. (July, 2011). Colorado’s 10 Winnable Battles. Retrieved from http://www.colorado.gov/cs/Satellite/CDPHE-Main/CBON/1251628821910

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., Lewis, F. M. (Eds.). (2002). Health Behavior and Health Education. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (November, 2006). Reducing Foodborne Illness Risk Factors in Food Service and Retail Establishments. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/FoodborneIllnessandRiskFactorReduction/ucm106205.htm

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (April, 2009). Voluntary National Retail Food Regulatory Program Standards. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/ProgramStandards/ucm180269.htm

Verlee, M. (2012, July 16). Restaurants Fines Leave Bad Taste. Colorado Public Radio. Retrieved from http://www.cpr.org/#load_article/Restaurants_Fines_Leave_Bad_Taste