Awareness of Food Safety Risks in Production of Produce on Oklahoma Farms

Bryan Buchwald

Section Director

Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food & Forestry

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2014 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Author Note

Bryan Buchwald, Section Director

Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food & Forestry

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort IV.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Bryan Buchwald (Bryan.Buchwald@ag.ok.gov).

Abstract

The Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, & Forestry (ODAFF) regulates the use of raw animal manure for certified organic producers, while other producers in Oklahoma are currently not regulated by ODAFF on the use of raw animal manure. This pilot study examined produce grower understanding of raw animal manure risk associated with foodborne illnesses in ready-to-eat produce. The study examined a small, convenience sample of large and small scale produce farms in Oklahoma regarding their use of raw animal manure in the production of ready-to-eat produce. The study included electronic surveys of 17 producers, paper surveys completed by 9 producers, and 15 in-person interviews with producers for a total of 41 produce growers. Interviews were conducted with 3 people with extensive regulatory experience in the produce industry. While the study results cannot be generalized due to the small, non-random sample size limited to one growing season, the results suggest significant risk of microbial contamination by Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, and various other pathogens in the production of ready-to-eat produce in Oklahoma. Recommendations include: (1) develop training and better education of produce farmers regarding raw animal manure use; (2) conduct outreach by delivering education and guidance to producers; and, (3) carry out performance of a larger, more rigorous, state-wide study that measures the producer knowledge and food safety risk associated with the application of raw animal manure in the production of ready-to-eat produce.

Keywords: Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), produce safety rule, raw animal manure

Background

Raw animal manure is a traditional fertilizer for farms. Raw manure is an excellent source of crop nutrients that maintains or improves soil organic matter content. The practice of using raw manure as fertilizer introduces the risk of contamination of crops and soil by pathogenic organisms, and foodborne illnesses have been linked to produce harvested from land where the producer applied untreated animal manure as a fertilization method prior to the harvest of the crop.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed a Produce Safety Rule to implement the produce safety requirements contained in the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), protect the public health, and minimize the risk of foodborne illness that would result from microbial-contaminated produce. This proposed rule addresses the use of raw animal manure. The original proposed rule included a nine-month interval between the application of raw animal manure and the harvest of produce. In September 2014, the FDA proposed deferring a decision on the appropriate interval between application and harvest until further research is conducted.

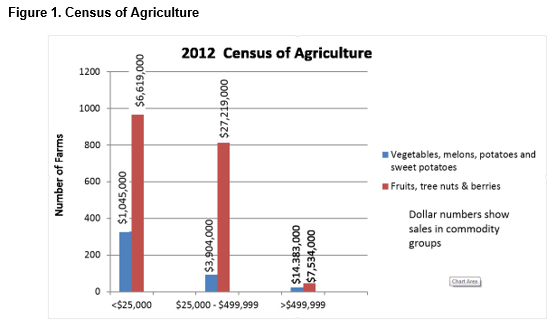

Even after the Produce Safety Rule is implemented, a large portion of the produce farms in Oklahoma will be exempt from coverage, because the farms do not meet business size requirements as illustrated in Table 1. Until further research and risk assessments can be completed and published by the FDA, the produce industry is using guidance found in the 1998 FDA Guide to Minimize Microbial Food Safety Hazards for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. At this time, this guidance is thought to be minimally used by Oklahoma produce farms, based on the fact that only three farms in Oklahoma are listed on the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service website as companies that meet USDA Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) acceptance criteria.

A wide variety of produce is grown in Oklahoma, including ready-to-eat produce with the edible portion grown in contact with the soil and also ready-to-eat produce that is not grown in contact with the soil. The method and timing of application of the raw animal manure to produce production areas could have an impact on food safety risks.

The number of Oklahoma produce farms that use untreated animal manure in the growing of ready-to-eat produce is unknown. Also unknown is whether produce growers that use untreated animal manure in growing ready-to-eat produce are aware of the food safety risks, and whether these producers are using GAPs to mitigate these risks and monitoring protocols to effectively monitor the level of risk.

Problem Statement

The Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food & Forestry (ODAFF) lacks comprehensive knowledge of the extent to which raw animal manure is used by ready-to-eat produce farmers, the degree of risk posed by the use of raw animal manure by these producers, and the typical level of producer knowledge regarding food safety risks, GAPs, and regulations associated with the use of raw animal manure in the production of ready-to-eat produce.

Research Questions

1. How common is raw animal manure use among producers of ready-to-eat produce?

2. What is the degree of risk posed by the use of raw animal manure by these producers, based on their method and time of application?

3. What is the typical level of producer knowledge regarding the food safety risks, GAPs, and regulations associated with the use of raw animal manure in the production of ready-to-eat produce?

Methodology

A random sample of Oklahoma producers was selected from three public database directories available through the ODAFF. These directories included the list of organic producers certified by ODAFF and two Oklahoma Buy Fresh Buy Local guides—one for the central region of Oklahoma and one for the Northeast region. An electronically-delivered, ten-question anonymous survey was sent to 85 producers, and 17 responded. A follow-up mail inquiry was then sent to all 85 producers, asking those that had not completed the electronic survey to complete and return a paper survey; nine were received. Finally, all 85 producers were called, and 15 who had not responded accepted invitations to complete the survey through individual or group interviews.

Of the in-person interviews, seven were individual interviews and two were group interviews. The length of the producer interviews ranged from five minutes to thirty minutes. Thirteen of the producers were from smaller produce farms, and two producers were from larger produce operations.

Results

Ninety percent of the producers market their produce directly to the consumer. Sixty-one percent of these producers use untreated raw animal manure as part of their fertilization program for the produce they grow. Sixty-four percent of those producers apply the untreated animal manure in the fall, and 80% of these producers incorporate the untreated animal manure into the soil in some manner. Figure 2 illustrates that 56% of the producers surveyed apply raw animal manure four months or less prior to harvest. None of the producers participating in the survey are testing produce at harvest for pathogens.

Conclusions

Untreated animal manure is being used cautiously by some producers as demonstrated by the fact that 44% of those surveyed reported application of raw animal manure greater than 9 months prior to harvest of ready-to-eat produce. Other producers appear unaware of the potential risks associated with the use of untreated animal manure as demonstrated by the fact that 56% of those surveyed reported application of raw animal manure 120 days or less prior to harvest. A portion of these producers use the 90/120-day interval as a rule of thumb to minimize food safety risks. However, the 90/120-day rule does not have a direct food safety objective. The primary objective in the National Organic Program Rule, 7 CFR Part 205 § 205.203, offers standards that are meant to maximize soil fertility; the 90/120-day rule can be found under this subpart. None of these producers are doing any type of testing of the produce at harvest for pathogens.

Recommendations

1. A larger, more rigorous study that measures the potential food safety risks throughout Oklahoma should be researched. Similar studies could be conducted in other states.

2. Training programs could be established through collaboration between federal, state, local, and tribal regulatory agencies and also industry and academia to develop risk-based best practices to support enhanced food safety.

3. Outreach should involve identifying the intended audience and effective methods of outreach for that audience. The produce industry has largely been unregulated in the past, so identifying and reaching these producers may prove to be challenging. Farming organizations and land grant university extension programs could be used to identify and then reach out to these producers.

4. Producers could be educated to institute risk-based preventive practices that mitigate known risks and enhance the production of a safe supply of produce. Also, education of these producers should be conducted to ensure that preventive measures are being taken in the production of ready-to-eat produce.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) for giving me the opportunity to participate in this Fellowship, as well as Stan Stromberg of the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food & Forestry for the agency’s support and allowing me the time to complete the program. I would like to thank the entire IFPTI staff and Board of Directors for such a rewarding experience. I would also like to thank the IFPTI educators, subject matter expert Paul Dezendorf, and especially my mentor, Steve Steinhoff, for all his guidance and input throughout my project and the entire Fellowship. I would also like to thank all the participants in the survey conducted as part of this research. I want to give a big thank you to all of the Fellows of Cohort IV for making this such an exceptional experience.

References

Flynn, D. (Jan. 2015). Choctaw leader: FDA should formally consult with tribes or exempt them from FSMA. Food Safety News. Retrieved from http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2015/01/choctaw-leader-tribal-nations-should-be-exempted-from-fsma/#.VTZTiiFViko

Kuepper, G. (2011). A basic summary of the national organic program manure and manure-compost regulations. Retrieved from Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture website: http://kerrcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/manure_rules.pdf

Mahovic, M. (2014). What is FDA doing to promote the safe use of manure and compost on crops? Questions and answers with Michael Mahovic. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/FSMA/ucm425766.htm

McGlynn, W., Dr. (2014). Oklahoma State University. Robert M. Kerr Food & Agricultural Products Center. http://fapc.biz/

Oklahoma Agriculture Food and Forestry. (2014). Oklahoma Organic Producers and Processors [Producers list used for survey]. Retrieved from http://www.oda.state.ok.us/food/ogl.pdf

Oklahoma Farm & Food Alliance. (2014). Producers list. [Producers list used for survey]. Retrieved from http://okfarmandfood.org/buy-fresh-buy-local/

U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agriculture Marketing Service. (2015). Companies that meet USDA GAP & GHP acceptance criteria. Retrieved from http://apps.ams.usda.gov/ReportServer05_69/Pages/ReportViewer.aspx?%2fGAP-GHP%2fG05+-+By+Location++-+Auditees+that+Meet+Acceptance+Criteria&rs:Command=Render

U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Statistics Service. (2012). Oklahoma Statistics [Quick Stats database]. Retrieved from http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Oklahoma/index.asp

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (1998). Guidance for industry: Guide to minimize microbial food safety hazards for fresh fruits and vegetables. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/ProduceandPlanProducts/UCM169112.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2015). Food Safety Modernization Act. Produce safety rule. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/FSMA/default.htm