The Impact of Native Language-Based Training on Food Safety Compliance in Suffolk County, New York

Lisa Potopsingh

Senior Public Health Sanitarian

Suffolk County Department of Health Services (SCDHS)

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2014 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Author Note: This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection. All correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lisa Potopsingh. Contact: Lisa.Potopsingh@suffolkcountyny.gov

Abstract

This study examined the effectiveness of native language-based food safety education on subsequent compliance levels in 150 food service establishments (FSEs) in Suffolk County, New York. A quantitative survey of FSE inspection reports was carried out to determine if compliance levels increased after at least one food service worker from the establishment completed the Food Manager’s Course provided by the Suffolk County Department of Health Services (SCDHS). A qualitative survey of New York State certified Food Service Inspection Officers from SCDHS was also carried out in order to provide context. Results from the quantitative survey suggest increased compliance following native language-based food safety education when compared with non-native based training. However, qualitative survey results indicate that addressing additional factors may strengthen the effect of education, thus promoting the goal of long-term compliance by FSEs in Suffolk County.

Keywords: Compliance through education, Food Manager Course, food service establishment (FSE), language-based training

Background

Foodborne disease is a common, but preventable, cause of illness worldwide (Jones & Angulo, 2006). The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) identified foodborne illness as a largely preventable public health burden (Food and Drug Administration [FDA] National Retail Food Team, 2009). FSMA’s goal is to proactively prevent food safety issues rather than react to problems once they have already occurred. Food safety compliance by food service establishments (FSEs) is particularly important due to the fact that restaurants and delicatessens contribute to two-thirds of outbreaks in the United States (Brown et al., 2014). In 2009, the FDA published results of a 10-year study that tracked the food industry’s effort to prevent foodborne illness (FDA National Retail Food Team, 2009). The study concluded that the presence of a certified food manager in FSEs was associated with higher compliance levels with regard to food safety practices and behaviors when compared to those facilities that lacked a certified food manager.

In 1975, Suffolk County became one of the first jurisdictions in the nation to implement and require food safety training. Since that time, providing education has become the trusted method to improve food safety compliance levels by FSEs in the County (C. Sortino, personal communication, 2014). Suffolk County’s food safety efforts and requirements are based upon the belief that education increases food safety compliance, which, in turn, will result in the operation of safer restaurants (Brown et al., 2014). A core component of Suffolk’s food safety education efforts is the Food Manager’s Course, which provides certification in food safety based on nine hours of classroom instruction. In an effort to keep the course content relevant, the course is actively monitored and changes are made to reflect new developments in food safety, as well as to meet the demands of an ever-changing audience.

As in other areas of the country, Suffolk County has experienced a substantial rise in its population of people who do not speak English as their primary language. As of 2010, approximately 20% of the County’s 1.5 million residents indicated that they do not speak English at home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). In order to provide food safety training to individuals whose primary language is Spanish, Suffolk County introduced a Spanish language version of the Food Manager’s Course in 2003. The course is taught by a native Spanish speaker certified by ServSafe®, a nationally-recognized food safety program accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI).

Local health departments differ across states and communities with regard to services provided. Common services provided by most local health departments are food safety education and performance of compliance inspections (Bekemeier, Yip, Dunbar, Whitman, & Kwan-Gett, 2015). Sufficient data and evidence required to adequately justify and distribute funds based upon the intrinsic value of food safety efforts is often not available to public health administrators (Bekemeier et al., 2015). Therefore, a study to determine the effectiveness of food safety education is fiscally and programmatically important.

Problem Statement

There has never been an evaluation to determine the relative effectiveness of the non-English language versions of the Food Manager’s Course as compared to the English language version for native speakers of other languages.

Research Questions

1. What is the difference in the level of compliance before and after attending a native language-based Food Manager’s Course?

2. What variables appear to be associated with the difference between the outcomes during subsequent inspections of establishments where a person has attended the Food Manager’s Course in their native language?

Methodology

A sample of 150 FSEs was chosen among the 4,700 regulated FSEs in Suffolk County. The sample was limited to those FSEs that employed at least one person with a valid food manager’s certificate and which were inspected by standardized sanitarians (who are accredited by the New York State Department of Health with the title of Food Service Inspection Officer Level-1 [FSIO-1]). Sanitarians in Suffolk County enforce Article 13 of the Suffolk County Sanitary Code. Results of inspection reports before and after a food service worker completed the Food Manager’s Course were examined. Establishments were separated into three groups, depending on how their certified food manager completed the course: Group 1 was comprised of native English speakers who completed the course in English; Group 2 consisted of native Spanish speakers who completed the course in Spanish; and Group 3 was comprised of native Chinese speakers who completed the course in English.

A secondary qualitative analysis was conducted by interviewing seven FSIO-1 sanitarians. The interviews provided information about the different methods used by inspectors to communicate with food service workers during routine inspections when the inspector and the worker do not speak a common language. Sanitarians were asked questions regarding the frequency of dealing with language barriers, different methods used to communicate during inspections, and their opinions regarding overall interactions with establishment employees and owners/operators.

Results

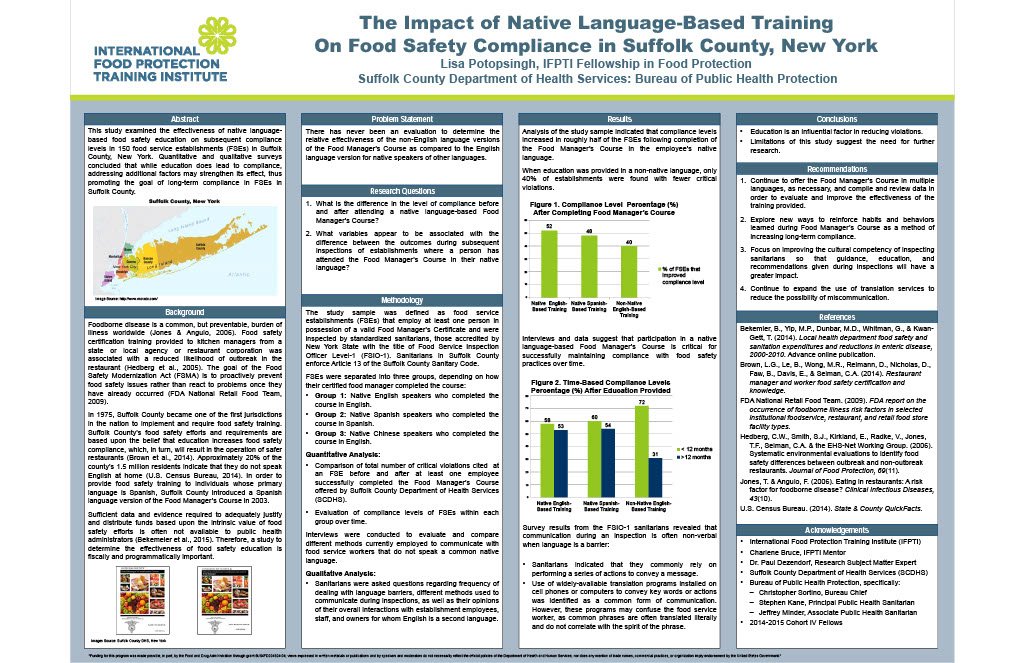

Compliance levels improved more for Spanish language-speaking FSE workers taking the course in Spanish (Group 2) and English language-speaking FSE workers (Group 1) as compared with FSE workers who took the course in English rather than in their native language (Group 3). Out of the 50 FSEs in which English was the primary language spoken, 26 respondents, or 52%, were cited for fewer critical violations after at least one food service worker completed the Food Manager’s Course (See Figure 1). This trend continued in FSEs where Spanish was the native language spoken by the food service workers, as 24 respondents out of 50, or 48%, were cited for fewer critical violations. In the establishments where Chinese was the predominately native spoken language and the food service worker completed the English-based Food Manager’s Course, the compliance level was found to be 40%, with 20 out of the 50 FSEs cited for fewer critical violations (See Figure 1).

Interviews with FSIO-1 certified sanitarians indicated that native language-based education is an important factor when attempting to increase compliance within a food service establishment. However, a theme noted throughout the interviews was that reinforcement of the food safety practices after participation in the Food Manager’s Course was critical for successfully maintaining compliance with food safety practices over time. Interviewees strongly believed that compliance is greatly influenced by timely reinforcement of learned behaviors. When an inspection was conducted within 12 months of course completion, the same number or fewer critical violations were cited for 58% of FSEs that completed native English-based training, 60% of FSEs that completed native Spanish-based training, and 72% of FSEs that completed non-native English-based training. When an inspection was conducted more than 12 months after course completion, these results dropped to 53% in Group 1, 54% in Group 2 and 31% in Group 3 (See Figure 2).

Survey results from FSIO-1 sanitarians also revealed that communication during an inspection is often non-verbal when language is a barrier. All sanitarians indicated that they commonly rely on performing a series of actions to convey a message, as this technique proves more effective when faced with a language barrier. The technique used most frequently by sanitarians is a method by which they “act out” the violation using hand gestures or create drawings in order to communicate the violation observed and the subsequent corrective action required.

Using widely-available translation programs installed on cell phones or computers to convey key words or actions was identified as a common form of communication, as well. However, sanitarians explained that these programs often confuse the food service worker, as common phrases are often translated literally and do not correlate with the spirit of the phrase. While these on-the-spot tactics may be effective at correcting a violation when observed, the tactics, according to the sanitarians surveyed, are not conducive to achieving long-term compliance.

Conclusion

Native language-based food safety education results in higher levels of food safety compliance (as seen in Figure 1). As observed in Figure 2, there was a stronger correlation in long-term compliance levels among Groups 1 and 2, where native language-based education was provided, when compared to Group 3, where education was not provided in the food service worker’s native language.

This conclusion is qualified by several limitations. First, the samples are relatively small. Second, compliance was measured simply by the number of critical violations rather than the types of critical violations. Third, Group 2 consisted of Spanish-speakers, while Group 3 was comprised of Chinese-speakers. This research might be improved if the native language of both Group 2 and Group 3 were the same.

Recommendations

1. Suffolk County should continue to offer food safety education in multiple languages as necessary, and compile and review data on an ongoing basis in order to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of the training provided.

2. Suffolk County should explore new ways to reinforce habits and behaviors learned during food safety training as a method of increasing long-term compliance.

3. Suffolk County should continue to improve the cultural competency of inspecting sanitarians so that guidance, education, and recommendations given during inspections will have a greater impact on achieving long-term compliance.

4. Suffolk County should continue to utilize and expand on the use of translation services to reduce the possibility of miscommunication due to language during the inspection process.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to take this opportunity to thank the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) for affording me the opportunity to participate in this unique and rewarding program. No words can describe the appreciation I have for my mentor, Charlene Bruce. I could not have done this without her unconditional, unwavering support. A special thanks to Dr. Paul Dezendorf, Ph.D., whose title as “Research Subject Matter Expert” seems woefully inadequate as the scope of his assistance seemingly knows no boundaries. Thank you to SCDHS, notably Bureau Chief Christopher Sortino; Principal Public Health Sanitarian Stephen Kane; and Associate Public Health Sanitarian Jeffrey Minder, for allowing me to participate in the Fellowship program. To all of my co-workers within the Bureau of Public Health Protection, thank you for all of the continued encouragement, assistance, and perspective. Thank you to all of my family and friends who continue to support me unconditionally. Last, but certainly not least, I would be remiss not to acknowledge the eight other Fellows: it has been an honor and a privilege to learn and grow with you. Your support knows no bounds, and I could not have asked for a better group of people with whom to complete this journey.