An Analysis of Regulatory Schemes Used Throughout the U.S. for Home-Based Food Businesses: Options Available to Enhance Food Safety

Courtney Rheinhart

Tidewater Regional Manager

Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2011 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

As economic growth has slowed and job loss has risen, many people are turning to the cottage food industry as a way to supplement their income. Increasing support for local foods has also caused individuals to aspire to start home-based food businesses. Regulators, however, have concerns that allowing foods to be produced in the home kitchen may lead to unsafe food and/or foodborne illnesses. The purpose of this study was to explore regulatory schemes currently being used by state agencies in regards to home-based food businesses. Further analyses were completed to compare the efforts of the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services to various other states’ regulatory actions regarding home-based food businesses. This study showed that there is little uniformity between state agencies when it comes to regulating food products produced in the home kitchen. This research suggests that state agencies need guidance to help them be more uniform regarding home-based food business regulations. This project also indicates that in Virginia, support of the cottage food industry has led to multiple inspection exemptions and policies that have negatively impacted the state’s regulatory authority over these home-based types of businesses to a greater degree than in other states.

Background

As the economy has weakened and unemployment has risen, the public has begun to look for ways to supplement their income. Many people are turning to the cottage industry as a way to make extra revenue. The term “cottage industry” is applied to an industry in which at least part of the manufacturing takes place in the home (Sutton, 2009). Requests from the public to regulatory agencies to manufacture food products in private homes are on the rise in Virginia as well as in other states. The “Buy Fresh- Buy Local” movement also supports small, home-based businesses. This movement encourages people to buy local food products and support local businesses and farmers. However, regulators fear that allowing food to be produced in the home and sold to the public with little or no oversight exposes consumers to dangers from foodborne illnesses and possibly from intentional food contamination (Wolfson, 2009).

Foodborne illness outbreaks and recalls of a food product can be catastrophic to a food manufacturer. In the case of a recall, the manufacturer often must pay to have the recalled product shipped and destroyed. Recalls can also have damaging effects on the public’s perception of the firm, and food safety regulation in general. Manufacturers may have to spend additional revenue to regain consumers’ trust and repair their damaged reputation. Such potential negative impacts are why the majority of large, non-home-based food manufacturers believe that investing ample resources into food safety will benefit their company.

Mainstream food manufacturers often rely on third-party audits to ensure that their processes, personnel, equipment, and establishment conform to food safety regulations and other standards (Hall, 2009). Manufacturers typically hire a quality assurance manager, someone with extensive food safety knowledge, to oversee day-to-day production and assure that the company is conforming to food safety guidelines implemented by regulators and/or the company’s buyers.

Large food manufacturers invest in equipment that not only creates a more efficient process, but that also allows the plant to implement effective cleaning practices. Many of the pieces of equipment found in food processing plants are designed so that crevices and other small openings where physical, chemical, or microbiological contaminants could collect are not present. Choosing this type of equipment helps food manufacturers to be profitable as well as provide a safeguard to reduce the potential risk of foodborne illness (Koch, 2011).

When food is produced in the home, the same standards of safety often cannot be met as those in the mainstream food processing facilities. Owners of home-based food businesses do not usually have an extensive background in food safety. They typically have not taken food safety courses and do not have a clear understanding of the regulations they must follow. In addition, they do not have the revenue to invest in third-party audits, quality assurance managers, or advanced equipment (Scott, 2003).

A review of studies from both Europe and North America showed that many cases of foodborne illness occur as a result of improper food handling by consumers in their own kitchens (Scott, 2003). In fact, a study conducted in Canada identified the home as the most common exposure location for cases of Salmonella species, Campylobacter species, and infectious E. coli. Inadequate cooking, reheating, and storage temperatures; cross contamination; and infected food handlers are the most common sources for foodborne pathogens in the home (Scott, 2003).

The home can be a multifunctional setting inhabited by residents of various ages and health conditions, which may impact food safety. Humans and animals living in the home may serve as sources of foodborne pathogens, and both can be symptomatic or asymptomatic carriers. Pets living in the home can range from typical to exotic, and foodborne illnesses can be acquired from either. Salmonella and other pathogens that cause intestinal illnesses are associated with household pets such as dogs and cats (Scott, 2003).

In Virginia, few restrictions are placed on home-based food businesses. As long as a home-based food business fills out an “Information Request Sheet for a Food Processing Operation,” has approved recipes and processes, can comply with the laws and regulations, and has been inspected by VDACS, there are no laws that prohibit the sale of a particular type of food product that falls under VDACS jurisdiction. Therefore, the types of foods produced in the home can range from cookies and cakes to baby food and acidified foods. In addition, for home-based food businesses that do not fall under inspection exemption in Virginia, there are also no limitations on where these products can be sold. Home food manufacturers may sell products directly to consumers, or they may sell to retail establishments in another state.

In Virginia, certain home-based food businesses are exempt from routine inspection. Support for the cottage food industry allowed Senate Bill 272 to be enacted in 2008. This bill exempts from inspection “private homes where the resident processes and prepares candies, jams and jellies not considered to be low-acid or acidified low-acid food products and baked goods that do not require time or temperature control after preparation if such products are: (i) sold to an individual for his own consumption and not for resale; (ii) sold at the private home or at farmers markets; and (iii) labeled “NOT FOR RESALE – PROCESSED AND PREPARED WITHOUT STATE INSPECTION” (Code of Virginia, 2011). Every year, additional legislation regarding inspection exemptions for cottage foods is proposed to the General Assembly.

Although VDACS requires the majority of home-based food manufacturers to be under inspection, limited resources are available to carry out these inspections. As of January 2011, more than 12,000 food facilities were on file with VDACS, but there were only 27 inspectors throughout the state. Home food manufacturers cannot be inspected as often as they should be, usually once every two years for a low-risk company. Mainstream non-home-based food manufacturers are usually inspected at least once per year. When inspections are conducted of mainstream, non-home-based food businesses, the inspections are unannounced, allowing the inspector to determine if the manufacturer is adequately assuring that routine practices are conducted in a safe and sanitary manner. On the other hand, inspections of home-based food manufacturers are scheduled. Therefore, inspectors are unable to determine whether the conditions they observe are representative of actual conditions that would be noted during unannounced inspections.

Problem Statement

Home-based food businesses present unique food safety and defense challenges to regulatory agencies throughout the United States. Since there may be few restrictions on the types of food products that can be produced in the home and where these products can be sold, there is the potential of an increased risk of unintentional foodborne illness outbreaks, as well as intentional contamination of home-produced food products. State food regulatory agencies may not be aware of all regulatory options available or the positive impacts these options may provide. Exploring how other regulatory agencies throughout the United States regulate home-based food businesses could provide policymakers in Virginia and in other states with additional options in regards to modifying regulatory oversight of these types of businesses.

Research Questions

What are the commonalities of and differences between state regulatory requirements for home-based food businesses in the United States? How do Virginia’s regulatory requirements compare to national estimates of state regulatory requirements for home-based food businesses in the United States?

Methodology

An analysis of existing state regulatory policies and procedures for home-based food manufacturers was conducted. Key personnel from regulatory agencies in the other 49 states who were responsible for food-related regulatory programs were contacted via e-mail and asked to participate in an online survey. The survey contained 24 questions that were developed to assess regulatory schemes currently used by other state agencies. These policies and procedures were then compared to the approach currently being used by VDACS.

Results

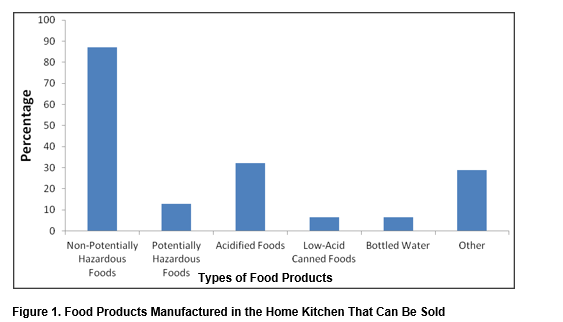

Of the 49 state agencies polled, 40 responded to the survey. Nine (22.5%) of the survey participants indicated that their state’s policies, procedures, or regulations do not permit the sale of food products manufactured in the home kitchen, while 31 (77.5%) responded that their states permit the sale of these types of food products. Of the 31 state agencies that allow the sale of food products manufactured in the home kitchen, 30 (96.8%) place restrictions on the types of food products that can be sold. Figure 1 shows the response to the second question of the survey, which asked about the types of food products manufactured in the home that may be sold. The survey asked the respondents to check all types of food products that apply.

Respondents did not use the “Other” section to address other types of food products, but instead used this section to provide further explanation. For example, one respondent wrote in the “Other” block that “A home food license … is limited to bakery items only.”

Out of the 30 states that place restrictions on the types of food products that can be sold, 17 (56.7%) only allow the sale of non-potentially hazardous food items. Of those 17, three place even further restrictions on the specific types of non-potentially hazardous foods that can be sold. One respondent stated that only non-potentially hazardous baked goods, dried herbs, and jams and jellies are permitted. Another responded that only non-potentially hazardous products that are baked or are a confectionary good are allowed; jams, jellies, and canned/bottled products are prohibited. Finally, another respondent replied that only certain baked goods, such as cookies, bread, and buns, may be manufactured and sold from the home kitchen. Of the 31 state agencies that allow home-based food businesses, only four (12.9%) permit the sale of potentially hazardous foods. Only one allows the sale of all types of food products (non-potentially hazardous food products, such as cookies, jams, jellies, and chips; potentially hazardous food products, such as cream-filled pies/cakes, meat products, and deli salads; acidified foods, such as salsas and pickled products; low-acid canned foods, such as canned green beans; bottled water). However, during a subsequent phone discussion with an official at this state agency, the official clarified that meat products cannot be produced from the home kitchen, and that acidified or low-acid canned food producers are required to have their product/process approved by a third party. The official also stated that at this, time the agency does not know of anyone producing low-acid canned foods from the home kitchen. Of the 30 states that place restrictions on the types of food products that can be sold, 22 (73.3%) also place restrictions on where these products can be sold. Figure 2 shows the response to the third question of the survey, which asked where food products produced in the home kitchen can be sold. The survey asked respondents to check all choices that apply.

Respondents from 14 (45.2%) of the 31 state agencies that allow food products to be manufactured in the home replied that their agencies license home-based businesses, while 17 (54.8%) stated that their agencies do not. Of the respondents who answered the question on whether their agency has the authority to inspect home-based food businesses, 18 (60%) stated that their agency does have the authority, while 10 (33.3%) responded that they do not. One respondent was unsure whether the agency had the authority to inspect home-based food businesses.

Of those respondents who answered the question on whether their agencies had any formal regulatory authority over home-based food manufacturers, all but two responded that they had some type of regulatory authority over these establishments. Types of regulatory authority included detention/embargo/seizure authority, authority to impose civil or administrative fines or penalties, authority to provide injunctive relief, authority to suspend or revoke a license, closure authority, and others.

When asked whether their state allows certain inspection exemptions for home-based food manufacturers, 15 (71.4%) respondents replied that their state allows exemptions, while six (28.6%) responded that their state does not. Six respondents (22.2%) indicated that operators of home-based businesses are required to attend some sort of training. Types of training varied from attending Better Process Control School to obtaining a Food Handler’s Card. Twenty-seven of the 29 respondents (93.1%) who answered the question on whether their agencies required foods produced in the home kitchens to be labeled replied that they did. Of those, 14 (51.9%) responded that the label must include a caveat stating that that the food was manufactured without inspection by the state regulatory authority.

Although a majority of respondents (56.7%) indicated that their agencies only permit non-potentially hazardous food items to be produced in the home kitchen, VDACS allows both potentially hazardous and non-potentially hazardous food items to be produced in the home kitchen. While 73.3% of the other state agencies place restrictions on where these types of products can be sold, VDACS allows these products to be sold anywhere.

The data compiled from this study show that although most of the state agencies allow the sale of food products manufactured in the home kitchen, the majority place some type of restriction on these types of businesses. These restrictions may involve the types of food products that can be manufactured, where those food products can be sold, training for the operator, a certain labeling requirement, or all of the above.

Conclusions

This survey revealed that regulatory authority varies greatly among state agencies. The research showed that there is a lack of uniformity in regards to the regulations used to oversee home-based food manufacturers. Many agencies may believe that the best way to protect public health is to place restrictions on the types of products produced in the home kitchen and where these products can be sold. However, other agencies may believe that these types of operations will exist regardless of whether restrictions are in place and that therefore, the best approach is to inspect every operation and provide training and guidance to operators.

The results of this survey demonstrated that VDACS does not place as many restrictions on home-based food businesses as other states. Providing educational outreach to home-based food operators in Virginia may address the current lack of regulatory authority over these types of businesses. In addition, presenting legislators and policymakers with these survey findings may prove useful and help prevent additional inspectional exemptions from being enacted.

Recommendations

Based on the results of this survey, one recommendation is that the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO) submit the Cottage Foods Regulatory Guidance document to the Conference of State Legislatures for potential adoption at the state level. State agencies should readdress their regulatory scheme regarding home-based food businesses so that the approach used matches up more closely with the AFDO guidance document. In addition, other research should be conducted to assess the training needs of home-based food business operators. In order to address any lack of regulatory oversight over these types of food businesses, state agencies should invest resources to provide training and information to operators of home-based food businesses. This information could be posted on the agency’s website, or an online training program could be created to allow operators to become more familiar with food safety regulations.

Acknowledgments

I would like to recognize the following individuals and entities for their support and contributions to this study: my mentor, Dan Sowards; the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI); AFDO; Dr. Craig Kaml, Vice President, Curriculum, IFPTI; Dr. Kieran Fogarty, Acting Director of Evaluation and Assessment, IFPTI, and Associate Professor, Western Michigan University; Joseph Corby, subject matter expert, IFPTI, and Executive Director, AFDO; all of the subject matter experts who participated in this cohort of the Fellowship program; the IFPTI staff; and the Cohort 2 IFPTI Fellows. I am especially grateful to Shana Davis, Senior Environmental Health Specialist, Lexington-Fayette County Health Department, and Shane Thompson, HACCP Coordinator, Wyoming Department of Agriculture, for providing guidance and constantly making me laugh throughout this process. I would also like to acknowledge Pamela Miles, Program Supervisor, Food Safety and Security Program, and Doug Saunders, Deputy Director, Division of Animal and Food Industry Services, both with VDACS, for allowing me to participate in the Fellowship and supporting me throughout my journey. Thanks also to Rick Barham, Regional Manager, VDACS, for his amazing editing skills. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to Gerald Wojtala, Executive Director, IFPTI, for the opportunity to participate in this Fellowship. It has truly been an honor to work with such a wonderful group of people.

Corresponding Author

Courtney Rheinhart, Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

Email: Courtney.Rheinhart@vdacs.virginia.gov

References

Article 3.2-5130. Miscellaneous Subjects. (2011). Code of Virginia. Retrieved from http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+3.2-5130

Hall, P. A. (2009, March 26). The value of third party independent audits in assuring food safety: Are they truly independent? A Presentation at IAFP’s Symposium on Salmonella in Peanut Products—Understanding the Risk and Controlling the Process. Retrieved from http://www.foodprotection.org/files/rr_presentations/RR_09.pdf

Koch, B. (2011). Packaging equipment design and food safety. Food Manufacturing. Retrieved from http://www.foodmanufacturing.com/scripts/ShowPR~PUBCODE~033~ACCT~0002488~ISSUE~0401~RELTYPE~PR~PRODCODE~009955~PRODLETT~A.asp

Scott, E. (2003). Food safety and foodborne disease in 21st century homes. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 14(5), 277-280. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2094945/

Sutton, Jim. (2009). Cottage industry may save modern America. Home Run Business. Retrieved from

http://www.homerun-business.com/cottage_industry.htm

Wolfson, Joshua. (2009, December 21). New rules prompt debate over food licensing. Trib.com. Retrieved from

http://trib.com/news/local/article_e7c3b293-7693-5e77-9bff-192066686e99.html