Potential Risks Associated with Raw Milk Consumption

Shane Thompson, REHS

Wyoming Department of Agriculture

Consumer Health Services

HACCP Coordinator

International Food Protection Training Institute

2011 Fellow in Applied Science, Law and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

Raw, unpasteurized milk products have been the confirmed source of several foodborne illnesses, outbreaks, and hospitalizations across the United States between 2005 and 2009. The purpose of this study was to determine if there was a relationship between the number of foodborne illnesses, outbreaks, and hospitalizations from raw milk products, and state regulations regarding the sale of raw milk products. Three different levels of regulation were identified, states that allow raw milk sales at retail (R); states that allow raw milk sales on the farm (F); and states that do not allow any raw milk sales for human consumption (N). There were no differences found between groups for the number of foodborne illnesses (P = 0.43), outbreaks (P = 0.89), or hospitalizations (P = 0.32) caused by raw milk products.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that approximately 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) get sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die every year from foodborne diseases (CDC, 2011c). Many techniques have been developed for food processing, in an attempt to make the foods we consume safer from harmful bacteria. One of these techniques is pasteurization, which has long been accepted as a process, which reduces foodborne illnesses. Pasteurization is most commonly achieved by heating milk to 161º F for 20 seconds (CDC, 2011a). In recent years, people have been consuming more foods that undergo less processing because they believe those foods to be healthier. As a result, there has been an increased demand for unpasteurized milk and milk-products.

Background

Many Americans are seeking healthier lifestyles in what has become a convenience-driven, unhealthy era. According to nutritionist Cynthia Sass, MPH, RD, a national spokesperson for the American Dietetic Association, “The biggest trend I see is a back-to-the-basic approach – getting away from highly processed foods and back to whole foods” (Bouchez, 2006). Milk is no exception, and with the demand for raw milk on the rise, opponents are concerned that the risks of drinking raw milk outweigh the perceived benefits (CDC, 2011a; CDC, 2011b; Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2011a; Raylea, Huck, Wiedmann, Boor, & Murphy, 2009).

According to the CDC, raw milk is milk from cows, goats, sheep, or other animals that has not been pasteurized. In the U.S., all milk products cause less than one percent of foodborne illnesses, and the sale of unpasteurized milk is estimated to account for less than one percent of milk sold to consumers (CDC, 2011b). On the contrary, around the turn of the 20th century, studies were conducted that linked raw milk to several disease outbreaks, and in fact, in 1938, raw milk caused 25% of all foodborne diseases in humans (Pasteurized Milk Ordinance [PMO], 2011).

Although not supported by empirical data, advocates of raw milk claim that pasteurization destroys enzymes, diminishes vitamin content, denatures fragile milk proteins, destroys vitamins C, B12, and B6, kills beneficial bacteria, promotes pathogens and is associated with allergies, increased tooth decay, colic in infants, growth problems in children, osteoporosis, arthritis, heart disease, and cancer (Realmilk.com, 2000).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other health agencies such as the CDC, and organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that raw milk is unsafe because of the potential to contain disease-causing pathogens such as Brucella, Campylobacter, Listeria, Mycobacterium bovis (a cause of tuberculosis), Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Shigella, and Yersinia (CDC, 2011b; FDA, 2011a; Ralyea et al., 2009). In the past 20 years, the nature of foodborne illnesses associated with dairy products has changed. Recently, raw milk product outbreaks have been primarily associated with Salmonella enteric, Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter jejuni, and Escherichia coli O157:H7 (Ralyea et al., 2009).

Although interstate sales of raw milk have been prohibited since 1987 (PMO, 2011), some states have recently legalized, in varying degrees, the intrastate sale of raw milk. Other states, however, have continued to prohibit the sale and distribution of raw milk intended for human consumption within their borders.

Problem Statement

The desire to sell, purchase, and consume raw milk is on the rise. The public, however, may not know the benefits, risks, and necessary regulations to ensure the safety of raw milk for consumption. The correlation between foodborne illnesses, outbreaks, and hospitalizations from raw milk consumption and the differences between state regulations that govern raw milk sales is not well defined.

Research Question

Is there a difference in the number of raw milk related foodborne illnesses, outbreaks, and hospitalizations between states that have differing levels of regulations?

Methodology

All dairy-related, foodborne illness data for Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), and Listeria monocytogenes were obtained through the National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS) from 1998 to 2009. This was the most current data available at the time of this study. Raw milk data were analyzed for the most recent five years of available data (2005-2009).

States (n=50) were divided into three different groups according to their regulations for selling raw milk. Groupings were based on a 2008 survey conducted by the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (Beecher, 2011). Twelve states allow raw milk sales at retail (R): Arizona, California, Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Utah, and Washington. Eighteen states allow raw milk sales on the farm (F): Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Twenty states do not allow the sale of raw milk for human consumption (N): Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Arkansas, Colorado, Mississippi, Missouri, South Dakota, Vermont, and South Carolina have unique regulations that did not match the category definitions precisely, so each state was assigned to the category that most closely resembled their regulations.

Data from each group were analyzed for incidence of raw milk product outbreaks, illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths. Because there were no deaths reported during the timeframe of this study associated with raw milk, no further analysis regarding deaths was carried out. The number of raw milk related outbreaks, illnesses, and hospitalizations for each group were calculated per 100,000 people, based on 2008 state populations (Information Please Database, 2010).

The number of raw milk associated outbreaks, illnesses, and hospitalizations caused by each of the four bacterial types (Salmonella spp., E. coli spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Campylobacter spp.) were also individually analyzed.

The data were analyzed using the PROC-GLM procedure in SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

There was one multi-state outbreak during the timeframe of this study in which E. coli O157:H7 was the etiological agent. The outbreak caused 18 illnesses and 5 hospitalizations, but because the states involved were not identified, the outbreak data was not included in this study.

Results

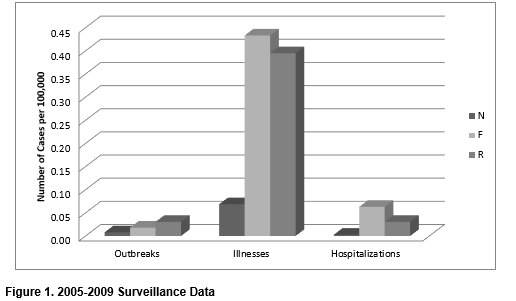

Although there was a greater number of outbreaks from raw milk products in states that allow sales at retail (R) than states that allow sales on the farm (F), and a greater number of outbreaks from states that allow sales on the farm than states that do not allow raw milk sales (N), the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.89). Similarly, there was a greater number of not only raw milk related illnesses, but also raw milk related hospitalizations in F than R, and R than F; however, differences were not significant between illnesses (P = 0.43) and hospitalizations (P = 0.32) among the different groups (Figure 1).

This figure illustrates the number of raw milk product outbreaks, illnesses, and hospitalizations per 100,000 people in the three study groups: states that do not allow raw milk sales (N); states that allow raw milk sales at the farm (F); and states that allow raw milk sales at retail (R).

Additionally, there were more illnesses associated with each outbreak for states that allow raw milk product sales vs. states that do not. In N, there were approximately 8.6 illnesses per outbreak associated with raw milk. In F, there were 23.7 illnesses per outbreak, and in R, there were approximately 12.9 illnesses per outbreak from raw milk products. Furthermore, there were fewer outbreaks, illnesses, and hospitalizations associated with raw milk in N than either F or R.

In addition, the data provides evidence that Campylobacter spp. was the most common cause of raw milk-related foodborne illness from 2005-2009, accounting for approximately 77% of all cases, followed by Salmonella spp., E. coli spp., and Listeria monocytogenes at 18%, 4%, and 1% respectively (Figure 2).

This figure shows the number of outbreaks, illnesses, and hospitalizations that have been linked to raw milk for the timeframe of this study for each of the four bacteria, Campylobacter spp., E. coli spp., Salmonella spp., and Listeria monocytogenes.

Conclusions/Recommendations

The popularity of raw milk is growing. In California alone, sales of raw milk increased 25% in 2010 (Raw-Milk-Facts.com, 2011). With the rapid expansion in sales, consumers need to understand the risks involved with consuming raw milk products, as well as the perceived benefits.

Although raw milk products make up approximately one percent of dairy production in the U.S., they account for 60 % of outbreaks caused by all dairy products, and people that consume raw milk products are 150 times more likely to contract foodborne illness than those that consume pasteurized products (CDC, 2012).

Proponents of raw milk claim that pasteurization destroys enzymes, diminishes vitamin content, denatures fragile milk proteins, destroys vitamins C, B12, and B6, kills beneficial bacteria, promotes pathogens and is associated with allergies, increased tooth decay, colic in infants, growth problems in children, osteoporosis, arthritis, heart disease, and cancer (Realmilk.com, 2000). However, both the FDA and CDC are strongly opposed to consuming raw milk, and have very different views compared to those that favor raw milk. According to the CDC (2011b), there are no health benefits from drinking raw milk that cannot be obtained from drinking pasteurized milk. The milk pasteurization process has never been found to be the cause of chronic diseases, allergies, or developmental behavioral problems (CDC, 2011b). Similarly, the FDA (2011b) states that pasteurizing milk does not cause lactose intolerance and allergic reactions. Both raw milk and pasteurized milk can cause allergic reactions in people sensitive to milk proteins (FDA, 2011b). Furthermore, pasteurization does not reduce milk’s nutritional value, or make milk safe to leave out of the refrigerator for extended time, particularly after the container has been opened (FDA, 2011b).

The risks associated with consuming raw milk products are very well documented (CDC, 2011b; CDC, 2011c; FDA, 2011a; FDA, 2011b), and even though there are perceived benefits to drinking raw milk, people that choose to drink raw milk need to be aware of the risks. The results of this study are a great educational tool that can be used to inform consumers of those risks, and give them an opportunity to see how many people have gotten sick and/or hospitalized from consuming raw milk.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) for giving me the opportunity to participate in this fellowship, and the experiences it has provided. I would also like to thank the American Food and Drug Officials (AFDO); Dr. Craig Kaml, Vice President of Curriculum; Dr. Kieran Fogarty, Acting Director of Evaluation and Assessment; the entire IFPTI Staff; all of the IFPTI educators; as well as the other fellows for their guidance and support. I would specifically like to thank my fellows, Courtney Rheinhart and Shana Davis, for their friendship, advice, and memories. I would also like to thank Dean Finkenbinder and Linda Stratton of the Wyoming Department of Agriculture for their support throughout my fellowship experience. I also want to thank Kelly Weidenbach for her assistance with data collection, and Katherine Kessler for her assistance with data analysis. I especially want to thank my mentor, Charlene Bruce, for her undying support and expertise throughout my project, and the entire fellowship.

Corresponding Author

Shane Thompson, Wyoming Department of Agriculture, Consumer Health Services

Email: shane.thompson@wyo.gov

References

Beecher, C. (2011). Ag Survey Compares States’ Raw Milk Regs. Food Safety News.

Retrieved from:

http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2011/07/no-change-in-states-allowing-raw-milk-

sales/

Bouchez, C. (2006). What’s New in Diet and Nutrition Trends. Retrieved from:

http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=59843

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Nonpasteurized Disease

Outbreaks, 1993-2006. Retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/rawmolk/nonpasteurized-outbreaks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011a). Food Safety and Raw Milk.

Retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/rawmilk/raw-milk-index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011b). Raw Milk Questions and

Answers. Retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/rawmilk/raw-milk-questions-and-answers.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011c). Estimates of Foodborne Illness in

the United States. Retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011d). Questions and Answers about

Foodborne Illness (sometimes called “Food Poisoning”). Retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/facts.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011e). Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks.

Retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/outbreaknet/outbreaks.html

Food and Drug Administration. (2011a). Questions & Answers: Raw Milk. Retrieved

from:

http://www.fda.gov./Food/FoodSafety/ProductSpecificInformation/MilkSafety/ucm122062.htm

Food and Drug Administration. (2011b). The Dangers of Raw Milk: Unpasteurized Milk

Can Pose a Serious Health Risk. Food Facts. Retrieved from:

http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm079516.htm

Information Please Database. 2010. U.S. Population by State, 1970-2010. Retrieved

from:

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0004986.html

National Outbreak Reporting System Data. (1998-2009).

Ralyea, R., Huck, J.R., Wiedmann, M., Boor, K.J., Murphy, S.C. (2009). Position

Statement on Raw Milk and Consumption. Cornell University Food Science

Department. Retrieved from:

http://foodscience.cornell.edu/cals/foodsci/extension/upload/CU-DFScience-

Notes-Raw-Milk-Position-Statement-12-09.pdf

Raw-Milk-Facts.com. (2011). Government Data Proves Raw Milk is Safe. Raw Milk in

the News. Retrieved from:

http://raw-milk-facts.com/inthenews.html

Realmilk.com. (2000). What is Real Milk? Retrieved from:

http://www.realmilk.com/what.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service and Food and

Drug Administration. 2011. Grade “A” Pasteurized Milk Ordinance. (2011).

Retrieved from:

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodSafety/ProductSpecificInformation/MilkSafety/NationalConferenceofInterstateMilkShipmentsNCIMSModelDocuments/UCM291757.pdf