Common Regulatory Critical Violations of Establishments in Florida with Adulterated Food Samples

Karla Clendenin

Senior Sanitation & Safety Specialist

Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2012 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (Florida) collects and analyzes approximately 1400 food samples each year. Samples are collected for various reasons including routine surveillance, discretionary sampling, and by contract with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When samples are found to be adulterated, the processor is notified and follow-up samples are subsequently collected and analyzed. This study was designed to identify trends found in Florida’s routine inspections that led to adulterated foods. Florida’s inspection data results indicated the lack of food protection to be the leading violative food safety practice cited in inspections of facilities that produced adulterated foods. The data also recognized the presence of pests, inadequate toilet and hand-washing facilities, maintenance of toxins, and plumbing issues as significant contributors.

Background

There is a shift in food regulation to be more prevention-oriented with the enactment of The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). When fully implemented, FSMA will require a written food safety plan to be implemented by food facilities that would include:

evaluating hazards that could affect food safety

specifying what preventive steps, or controls, will be put in place to significantly minimize or prevent the hazards

specifying how the facility will monitor these controls

maintaining routine record of the monitoring

specifying what action the facility will take to correct problems that arise.

Furthermore, FDA has established prevention-oriented standards and rules for seafood, juice, and eggs, as has the U.S. Department of Agriculture for meat and poultry, and many in the food industry have pioneered “best practices” for prevention (Hamburg, 2011). This proactive shift in paradigm requires a great deal more foresight by both the regulated and the regulator.

Six state agencies share the responsibility of inspecting food facilities in Florida. Retail establishments, including convenience stores and grocery markets, comprise the bulk of the inspections conducted under the jurisdiction of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services’ Division of Food Safety. Manufacturers. Processors, packers, and warehousing operations make up the remaining inspections. Food inspection reports typically provide a snapshot of violative food safety practices taking place at the time of the inspection. Food samples are routinely collected as part of the inspection process and analyzed in Florida’s food laboratories. The International Standards Organization (ISO) has accredited the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services food laboratories. ISO accreditation is a recognized independent evaluation of a laboratory’s competence to perform to international standards. When laboratory analyses indicate foods are adulterated in Florida, a protocol to remove the product from commerce is initiated in addition to addressing the sources of contamination.

Consumers demand a safe food supply and government is responding by requiring proactive food safety practices. In this prevention-oriented atmosphere, noting violations on inspection reports is no longer an adequate response. Rather, the inspection report and the analyses of the collected samples are verification that the proactive food safety practices are effective.

Government regulators and the regulated industry have a common goal to avoid a possible food safety crisis. If more emphasis can be placed on the cooperative approach to prevention during inspections, a reduction in violative food safety practices may be achieved. Partnering with industry may serve as a platform for collaborative process improvements in food safety as long as the relationship does not compromise the public interest (Sparrow, 2000).

Problem Statement

Compliance strategies are broadly reactive when adulterated food is discovered through laboratory analysis. This study is designed to identify trends found in Florida’s routine inspections that preceded the discovery of contamination. By utilizing this trend data, regulators may initiate intervention techniques and outreach efforts in a proactive and collaborative approach with the regulated industry, thereby reducing the factors that are historically shown to lead to contamination.

Research Questions

1) Within Florida, what are the adulterants most frequently detected through laboratory analysis?

2) What are the violations with a critical component most frequently documented during routine inspections prior to a laboratory finding of an adulterated sample?

Methodology

Secondary data analysis was conducted on inspection and laboratory reports for food facilities under the regulatory authority of Florida’s Division of Food Safety that produced adulterated food samples in 2010 and 2011. Sample data was collected from Florida’s Bureau of Food Laboratories and inspectional data was collected from Florida’s Division of Food Safety. Incidents of laboratory detection of contamination at a facility were cross-referenced with the three inspection reports for that facility prior to the detection of contamination. Violations noted on inspection reports were analyzed using a spreadsheet computer program to determine if common violations were found. Violations are categorized in Florida as critical and non-critical; only the broad categories of violations that had a critical component were included in the results. For the purposes of this study, the term “adulterated” is used to describe samples that include either recognized illegal contaminants or indicators of contamination such as the presence of high levels of coliform bacteria or E. coli.

Results

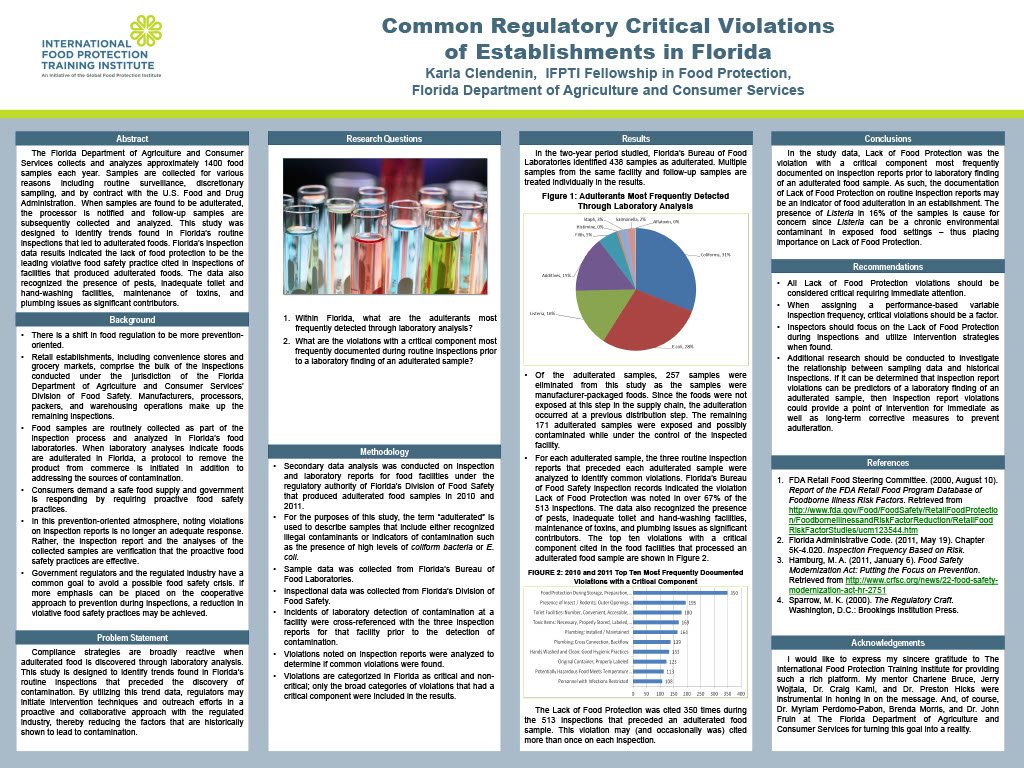

In the two-year period studied, Florida’s Bureau of Food Laboratories identified 438 samples as adulterated. Multiple samples from the same facility and follow-up samples are treated individually in the results. Laboratory reports indicated unsafe levels of coliforms, including fecal coliforms, were present in 31% of the adulterated samples. E. coli and Listeria were found in 28% and 16% of the samples, respectively. Undeclared or harmful ingredients were present in 15% of the samples. The remaining 10% of the adulteration was due to filth, staphylococcus, salmonella, histamine formation, and aflatoxin.

Of the 428 adulterated samples, 257 samples were eliminated from this study as the samples were manufacturer-packaged foods. Since the foods were not exposed at this step in the supply chain, the adulteration occurred at a previous distribution step. The remaining 171 adulterated samples were exposed and possibly contaminated while under the control of the inspected facility. For each adulterated sample, the three routine inspection reports that preceded each adulterated sample were analyzed to identify common violations. Five adulterated samples did not have three (3) previous inspections to review as the facilities were too new to have a history of at least three inspections. Additionally, inspectors cited violations during an unrated industry visit (while delivering lab results) 16 times. An industry visit should not contain violations, but inspections do. These visits were included in the analysis as a fourth inspection of the facility.

Florida’s Bureau of Food Safety inspection records indicated the violation Lack of Food Protection was noted in over 67% of the 513 inspections (Figure 2). The data also recognized the presence of pests, inadequate toilet and hand-washing facilities, maintenance of toxins, and plumbing issues as significant contributors. The top ten violations with a critical component cited in the food facilities that processed an adulterated food sample are shown in Figure 2.

The Lack of Food Protection was cited 350 times during the 513 inspections that preceded an adulterated food sample. This violation may (and occasionally was) cited more than once on each inspection. For example, an inspector may have cited the violation (Lack of Food Protection) in the warehouse and also in the processing room for different commodities or processes).

Conclusions

In the study data, Lack of Food Protection was the violation with a critical component most frequently documented on inspection reports prior to laboratory finding of an adulterated food sample. As such, the documentation of Lack of Food Protection on routine inspection reports may be an indicator of food adulteration in an establishment. The presence of Listeria in 16% of the samples is cause for concern since Listeria can be a chronic environmental contaminant in exposed food settings – thus placing importance on Lack of Food Protection.

Recommendations

The Lack of Food Protection violation and all of the “canned text embellishments” should be critical violations. The eight “canned text embellishments” that can be added by the inspector are:

· Improper and or no datemarking on ready-to-eat food held for more than 24 hours.

· Barriers are not in place to control C. botulinum toxin formation when using reduced-oxygen packaging.

· Food is not protected from contamination during preparation.

· Food is not protected from contamination during transportation.

· Food is stored or displayed in a location subject to contamination.

· Food is stored or displayed on the floor.

· Food is stored or displayed on unclean surfaces.

· Food is stored or displayed uncovered and exposed to contamination.

In Florida, critical sanitation violations are required to be addressed immediately. Only the top two “canned text embellishments” are critical sanitation violations: date-marking and controls for reduced-oxygen packaging. The other six embellishments are non-critical violations.

When assigning a performance-based variable inspection frequency, critical violations should be a factor rather than the overall rating, as is the current policy. Food establishments in Florida are subject to a variable inspection frequency based on performance (Florida Administrative Code, 2011). A food establishment may require a higher frequency when deemed necessary or reduced frequency with continual compliance. Together the most vulnerable food facilities will be inspected more frequently.

Florida should then utilize food surveillance sampling data and historical inspections as a tool to identify the factors and behaviors that lead to adulterated food. Relevant and timely data can be a powerful tool that can be shared on a collaborative platform for process improvement.

Inspectors can focus on the Lack of Food Protection during their inspections, which could be considered as a leading risk factor for food contamination in Florida. By communicating and placing emphasis during routine inspections on this risk factor, food contamination may be averted. Intervention strategies, risk-control plans, and other outreach efforts may pioneer a best practice for prevention.

Additional research should be conducted to investigate the relationship between the notation of the top ten most documented violations with a critical component and the laboratory finding of an adulterated sample. If it can be determined that inspection report violations can be predictors of a laboratory finding of an adulterated sample, then inspections could provide a point of intervention for immediate as well as long-term corrective measures to prevent adulteration.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to The International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) and Vice President Dr. Craig Kaml for providing such a rich platform through the 2012-2013 Fellowship in Food Protection program with unprecedented access to subject matter experts; my career path will forever be changed. This project could not have been completed without the wise guidance of my mentor Charlene Bruce, Dr. Preston Hicks, and Gerald Wojtala; they were instrumental in honing in on the message. The re-creation of the wheel was often averted with the guidance and open access from Sanitation and Safety Administrator Dr. Myriam Perdomo-Pabon, Environmental Administrator Brenda Morris, and Bureau Chief Dr. John Fruin at The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Corresponding Author

Karla Clendenin, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Food Safety

Email: Karla.Clendenin@freshfromflorida.com

References

FDA Retail Food Steering Committee. (2000, August 10). Report of the FDA Retail Food Program Database of Foodborne Illness Risk Factors. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/FoodborneIllnessandRiskFactorReduction/RetailFoodRiskFactorStudies/ucm123544.htm

Florida Administrative Code. (2011, May 19). Chapter 5K-4.020. Inspection Frequency Based on Risk.

Hamburg, M. A. (2011, January 6). Food Safety Modernization Act: Putting the Focus on Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.crfsc.org/news/22-food-safety-modernization-act-hr-2751

Sparrow, M. K. (2000). The Regulatory Craft. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.