Food Code Adoption and Food Safety Training within the Bemidji Area Indian Health Service

LTJG Scott Daly, REHS

Field Environmental Health Officer

Indian Health Service

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2012 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

This paper explores food code adoption and food safety training within the Bemidji Area Indian Health Service (BAIHS). The BAIHS serves 34 federally-recognized tribes in the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana. The adoption of the FDA Food Code is not uniform among the tribes in the BAIHS, and no data exists on whether the manager and basic food handler training requirements to achieve active managerial control are being satisfied. A 13-question Survey Monkey questionnaire was sent via email to each of the 15 Environmental Health Specialists (6 federal employees and 9 tribal employees) who provide services to the 34 tribes in the BAIHS. Each of the 15 Environmental Health Specialists completed the questionnaire for a response rate of 100%. The results indicate 62% of the tribes in the BAIHS do not have a food code adopted at the tribal level based on the FDA Food Code and only 3 tribes have a food code based on the current 2009 FDA Food Code. Certified food protection manager (CFPM) training is required by 38% of the tribes but 85% of the tribes provide CFPM training as best practice. Basic food handler training is required by 26% of the tribes but 79% of the tribes provide basic food handler training as best practice. CFPM training and basic food handler training is a critical component of active managerial control. The survey results identify a significant gap in terms of achieving an integrated food safety system. Priority should be given to adopting or updating the tribal food codes within the BAIHS and to developing a standardized operating procedure to prioritize CFPM and basic food handler training among food service employees.

Background

The Bemidji Area Indian Health Service (BAIHS) serves 34 federally-recognized tribes in the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana. Encompassing an area of 5,183 square miles and serving approximately 110,000 American Indians, the BAIHS maintains two district offices: the Minnesota District Office, which serves 11 tribal nations in Minnesota, and the Rhinelander District Office, which serves 23 tribal nations in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana. Each tribe within the BAIHS has two options to receive environmental health services: either directly through the Indian Health Service (IHS) Division of Environmental Health Services (DEHS), or through their own Tribal Environmental Health Specialists. IHS DEHS employs 6 field Environmental Health Specialists to provide services to 23 tribes in the BAIHS. The remaining 11 tribes receive services from their own individual Tribal Environmental Health Specialists.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) publishes the Food Code to serve as a guide for state, local, territorial, and tribal jurisdictions to regulate the retail food service industry. The FDA Food Code is a framework for safeguarding the public health and ensuring food is unadulterated and honestly presented to the consumer. There have been eight Food Codes issued by the FDA since 1993; the 2009 Food Code is the most recent. The FDA Food Code establishes practical, science-based guidance and enforceable provisions for mitigating risk factors known to cause foodborne illness. The FDA Food Code is neither federal law nor federal regulation and it is not preemptive. Rather, the Food Code represents FDA’s best advice for a uniform system of regulation to ensure that food at retail is safe and properly protected and safeguarded.

The importance of food safety integration has been discussed for years by the regulatory community and is a major focus point in the Food Safety Modernization Act, which was signed into law by President Obama on January 4, 2011. The FDA identifies partnerships with retail food industry, state, local, and tribal authorities, and other government agencies as fundamentally key to the success of its Retail Food Safety Initiative (FDA, 2011). The Retail Food Safety Initiative is part of the FDA’s overall shift in regulatory philosophy: moving away from a reactive approach to a proactive, prevention-based, food safety strategy to reduce foodborne illness (FDA, 2011). After a 10-year study assessing retail food establishment control of five key foodborne illness risk factors (food from unsafe sources, inadequate cooking, improper holding temperatures, contaminated equipment, poor personal hygiene), the FDA identified four action areas to address: 1) make the presence of certified food protection managers (CFPMs) common practice; 2) strengthen active managerial control at retail and ensure better compliance; 3) encourage widespread, uniform, and complete adoption of the FDA Food Code; and 4) create an enhanced local regulatory environment for retail food operations (FDA, 2011).

The 2009 FDA Food Code defines active managerial control as the purposeful incorporation of specific actions or procedures by industry management into the operation of their business to attain control over foodborne illness risk factors. A prominent element of active managerial control is manager and employee food safety training. The 10-year study conducted by the FDA concluded that having a CFPM has a positive impact on food safety and should become common industry practice (FDA, 2011). Moreover, in 2010 the Conference for Food Protection (CFP) sent a request to the FDA to modify the Food Code to require that at least one “Person in Charge” in each food establishment be certified according to a CFP recognized program (CFP, 2010). The CFP request was based on a study published in the Journal of Food Protection that suggests the presence of a CFPM, defined as managers who received a certificate upon completion of a food safety training course, was the major distinguishing factor between restaurants in which foodborne illness occurred and restaurants in which foodborne illness outbreaks did not occur (Hedberg, 2006).

Federally recognized tribes are sovereign nations and are not subject to federal, state, or local laws. Tribal sovereignty allows each tribal nation to adopt and enforce their own laws, including those regarding food safety. Each tribal nation has the same authority as any state, territory, or local agency to adopt the FDA Food Code.

Problem Statement

The adoption of the FDA Food Code is not uniform among the tribes in the Bemidji Area Indian Health Service, and no data exists on whether the manager training and basic food handler training requirements to achieve active managerial control are being satisfied.

Research Questions

1.) What is the current level of FDA Food Code adoption among the tribes in the Bemidji Area Indian Health Service?

2.) What type of training is required for tribal food managers and food handlers in the Bemidji Area Indian Health Service?

3.) What type of training is provided to tribal food managers and food handlers in the Bemidji Area Indian Health Service?

Methodology

A 13-question electronic questionnaire was sent via email to each of the 15 IHS DEHS and Tribal Environmental Health Specialists who provide field services for the 34 tribes in the BAIHS. The email contained a two-paragraph explanation and overview of the project and an embedded link to a Survey Monkey questionnaire. The questions asked about the level of FDA Food Code adoption for each tribe and what food manager and food handler training is required and/or provided by each tribe. The responses for level of FDA Food Code adoption were tiered into three groups: 1) 2009 edition adopted; 2) 2005 or earlier edition adopted; and 3) njo food code adopted. Environmental Health Specialists who serve more than one tribe were asked to complete the questionnaire for each tribe he/she works with. Participants were given a two-week timeframe to complete the questionnaire. Those participants who did not complete the questionnaire were encouraged to do so with a follow-up phone call. The questionnaire was completed by each of the 15 Environmental Health Specialists for a response rate of 100%.

Results

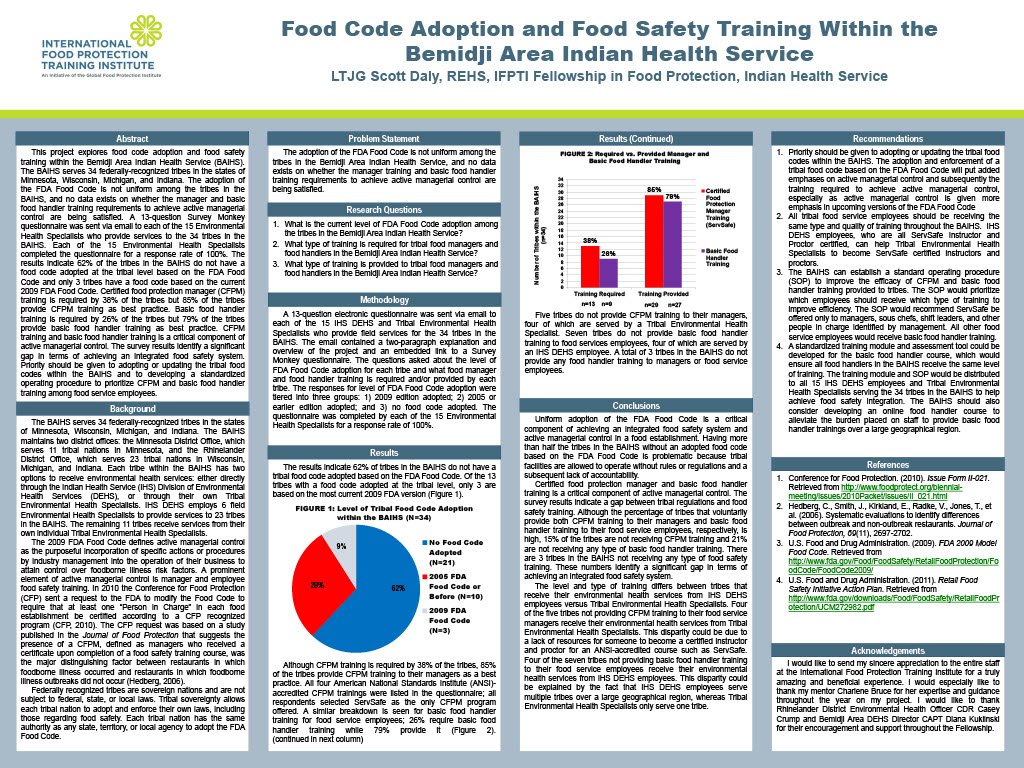

The results indicate 62% of tribes in the BAIHS do not have a tribal food code adopted based on the FDA Food Code. Of the 13 tribes with a food code adopted at the tribal level, only 3 are based on the most current 2009 FDA version (Figure 1).

Although CFPM training is required by 38% of the tribes, 85% of the tribes provide CFPM training to their managers as a best practice. All four American National Standards Institute (ANSI)-accredited CFPM trainings were listed in the questionnaire; all respondents selected ServSafe as the only CFPM program offered. A similar breakdown is seen for basic food handler training for food service employees; 26% require basic food handler training while 79% provide it (Figure 2).

Five tribes do not provide CFPM training to their managers, four of which are served by a Tribal Environmental Health Specialist. Seven tribes do not provide basic food handler training to food services employees, four of which are served by an IHS DEHS employee. A total of 3 tribes in the BAIHS do not provide any food handler training to managers or food service employees.

Conclusions

Uniform adoption of the FDA Food Code is a critical component of achieving an integrated food safety system and active managerial control in a food establishment. Having more than half the tribes in the BAIHS without an adopted food code based on the FDA Food Code is problematic because tribal facilities are allowed to operate without rules or regulations and a subsequent lack of accountability. Moreover, 77% of the tribes with an adopted food code have adopted codes that are not based on the most current (2009) FDA version, which contains recommendations based on the most up-to-date science.

Certified food protection manager and basic food handler training is a critical component of active managerial control. The survey results indicate a gap between tribal regulations and food safety training. Although the percentage of tribes that voluntarily provide both CPFM training to their managers and basic food handler training to their food service employees, respectively, is high, 15% of the tribes are not receiving CFPM training and 21% are not receiving any type of basic food handler training. There are 3 tribes in the BAIHS not receiving any type of food safety training. These numbers identify a significant gap in terms of achieving an integrated food safety system.

The level and type of training differs between tribes that receive their environmental health services from IHS DEHS employees versus Tribal Environmental Health Specialists. Four of the five tribes not providing CFPM training to their food service managers receive their environmental health services from Tribal Environmental Health Specialists. This disparity could be due to a lack of resources for someone to become a certified instructor and proctor for an ANSI-accredited course such as ServSafe. Four of the seven tribes not providing basic food handler training to their food service employees receive their environmental health services from IHS DEHS employees. This disparity could be explained by the fact that IHS DEHS employees serve multiple tribes over a large geographical region, whereas Tribal Environmental Health Specialists only serve one tribe.

Recommendations

Priority should be given to adopting or updating the tribal food codes within the BAIHS. The adoption and enforcement of a tribal food code based on the FDA Food Code will put added emphases on active managerial control and subsequently the training required to achieve active managerial control, especially as active managerial control is given more emphasis in upcoming versions of the FDA Food Code. The tribes should also be encouraged to ensure the tribal food codes automatically update when a new version of the FDA Food Code is issued. This approach will ensure the tribal food code is based on the most current and up-to-date science.

All tribal food service employees should be receiving the same type and quality of training throughout the BAIHS. Since a majority of the tribes not providing CFPM training to their food service managers are served by Tribal Environmental Health Specialists, IHS DEHS employees can assist them with building their capacity to provide CFPM training such as ServSafe. IHS DEHS employees, who are all ServSafe Instructor and Proctor certified, can help Tribal Environmental Health Specialists to become ServSafe certified instructors and proctors. This approach would allow food service managers to be trained onsite, reducing the cost associated with course and instructor fees for off-site training.

Since IHS DEHS employees are responsible for providing environmental health services to several tribes over a large geographical area, time is a valuable resource and time spent on training should be as efficient as possible. ServSafe consumes valuable employee time teaching and preparing for the course. The BAIHS can establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) to improve the efficacy of CFPM and basic food handler training provided to tribes. The SOP would prioritize which employees should receive which type of training to improve efficiency. Since ServSafe is designed for food service “managers” the SOP would recommend ServSafe be offered only to managers, sous chefs, shift leaders, and other people in charge identified by management. All other food service employees would receive basic food handler training. This strategy would improve the efficacy of time spent preparing and teaching ServSafe to food service employees who do not need manager-level training.

A standardized training module and assessment tool could be developed for the basic food handler course, which would ensure all food handlers in the BAIHS receive the same level of training. The training module and SOP would be distributed to all 15 IHS DEHS employees and Tribal Environmental Health Specialists serving the 34 tribes in the BAIHS to help achieve food safety integration. The BAIHS should also consider developing an online food handler course to alleviate the burden placed on staff to provide basic food handler trainings over a large geographical region. An online course may increase the number of food handlers trained by making the training more convenient for tribal employees.

The basic food handler training would be developed by Registered Environmental Health Specialists and would be based on the latest science and information from the FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Subsequent research can evaluate the effectiveness of basic food handler training.

Acknowledgments

I would like to send my sincere appreciation to the entire staff at the International Food Protection Training Institute for a truly amazing and beneficial experience. I would especially like to thank my mentor Charlene Bruce for her expertise and guidance throughout the year on my project. I would like to thank Rhinelander District Environmental Health Officer CDR Casey Crump and Bemidji Area DEHS Director CAPT Diana Kuklinski for their encouragement and support throughout the Fellowship.

Finally, I would like to thank my Mom and Dad for their continuous love and unwavering support.

References

Conference for Food Protection. (2010) Issue Form II-021. Retrieved From:

http://www.foodprotect.org/biennial-meeting/issues/2010Packet/issues/II_021.html

Hedberg C, Smith J, Kirkland E, Radke V, Jones T, et al. (2006). Systematic

Evaluations to Identify Differences Between Outbreak and Nonoutbreak Restaurants. Journal of Food Protection, 69(11), 2697-2702.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009). FDA Model Food Code. Retrieved From:

http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/FoodCode/FoodCode2009/

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011). Retail Food Safety Initiative Action Plan.

Retrieved From: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/UCM272982.pdf