Use of Critical Control Points (CCPs) In Florida Seafood HACCP Plans

Matthew Coleman

Environmental Manager

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2017 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Author Note

Matthew Coleman, Environmental Manager, Manufactured Food

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort VI.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Matthew Coleman, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 3125 Conner Blvd., Tallahassee, FL 32399

Email: MatthewColeman@FreshFromFlorida.com

Abstract

The Critical Control Points (CCPs) in Fish and Fishery Products Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (Seafood HACCP) plans from 158 Florida wholesale seafood establishments were evaluated for food hazard significance, probability, and likelihood to occur within the food establishment’s process, end product, and intended consumer use. The plans were obtained from onsite, rated inspections during the period October 1, 2014, to September 30, 2016, carried out by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) under FDA contract.

The study found that a substantial percentage of the CCPs, 105 of 440 or 23.9%, were not significant, probable, or reasonably foreseeable food hazards within that given process and/or end product nor were they required by 21 CFR Part 123. These CCPs, termed “negligible elements” in the study, were found in 63 of the 158 plans (39.9%); in fact, 9 of those 63 plans (14.3%) did not include a single valid CCP. The study also found that these negligible elements were distributed among small, medium, and large firms in proportion to the number of firms in those categories.

The study recommends further studies to determine whether the conclusions of this study might apply beyond Florida; whether negligible elements might be controlled by other means; the potential extent and cost of HACCP report bias due to negligible elements; opportunities to overcome the negligible element problem by training or outreach; and whether the problems found in Seafood HACCP plans might also occur in Preventive Controls for Human Food and food safety plans.

Key words; Seafood Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plans; Critical Control Points (CCPs); 21 CFR Part 123; Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance (4th edition).

Background

Mandatory Fish and Fishery Products Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) (hereinafter referred to as Seafood HACCP) preventive measures have been in place for nearly 20 years in Florida. During this period, some seafood processors appear to have incorporated elements as Critical Control Points (CCPs) that may not be significant, reasonably foreseeable and/or probable food hazards within the specific process and/or end product, termed “negligible elements” in this study. For example, anecdotal evidence suggests that some seafood establishments may be using their Seafood HACCP plan as a repository for a broad range of company, program and/or customer-specific rules that are only related in a minor way, if at all, to food safety in regard to the given process and end product. In other cases, differing end products and processes are included into one single HACCP plan, thus unnecessarily applying CCP(s), monitoring, and verification steps to an end product and/or a process where a food hazard may not be significant, reasonably foreseeable and/or likely. The continuing and perhaps growing use of seafood HACCP plans as a “catch all” location for company, customer and/or third party specific information by creating negligible elements has the potential to cloud the purpose of Seafood HACCP plans to the seafood establishment operator.

For regulators, the inclusion of negligible elements appears to have the potential to undermine the statistical validity of the Seafood HACCP system. For example, an unlikely food safety element as a CCP in a HACCP plan, an element not required by 21 CFR Part 123, may be found in violation and thus count toward a HACCP violation but have nothing to do with HACCP. The continued use of these negligible elements may misstate the actual situation regarding Seafood HACCP violations in the State of Florida and as a result divert resources from other food safety regulatory areas.

As a result of these concerns, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS), Division of Food Safety authorized the time for the author to pursue his concerns about Florida Seafood HACCP reporting.

Problem Statement

The extent to which negligible elements are incorporated as Critical Control Points (CCPs) in Florida Seafood HACCP plans is unknown.

Research Questions

1. What is the distribution of required CCPs and negligible elements in seafood establishment HACCP plans?

2. What is the percentage of negligible elements incorporated into seafood HACCP plans?

3. What percentage of food establishments incorporate negligible elements as CCPs that could be monitored as SSOPs?

4. Is there any correlation between the inclusion of negligible elements in Seafood HACCP plans and the food establishment size?

Methodology

A total of 158 seafood HACCP plans acquired during rated inspections, under FDA contract, of seafood wholesale establishments from October 1, 2014, to September 30, 2016, were used as a sample for this project. Those plans were evaluated for biological, chemical, and physical potential hazards in relation to one end product and process using the information obtained at time of inspection (including inspector flow charts, inspector hazard analysis, and the seafood establishment’s HACCP plan) and 21 CFR Part 123, and the Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance (4th edition). Each CCP was then scored in regard to a food hazard that was reasonably foreseeable, significant, and probable or as a negligible element within the specific process, end product and intended consumer use. The evaluation of these CCPs considered the specific end product package (air package or modified air packaging), process steps and time, product holding state (frozen or refrigerated) and the intended end consumer use (raw, cooked or further processed).

In order to test for the relationship between the inclusion of negligible elements and the size of the seafood establishment, the seafood establishments were assigned to one of ten categories based on annual gross sales estimated by the seafood establishment at the time of rated onsite inspection. Those ten categories were then broken into three groups: Small ($0 to $499,999), Medium ($500,000 to $9,999,999) and Large ($10,000,000 and up). The size categorization was used to test whether a firm’s size was associated with the likelihood of use of negligible elements.

Results

A total of 440 individual CCPs were identified and reviewed in the 158 HACCP plans evaluated. A total of 335 out of the 440 CCPs reviewed (76%) were reasonably foreseeable, significant, and probable food hazards within the specific process, end product and/or intended customer use. However, 105 out of the 440 CCPs reviewed (23.9%) appeared to be negligible elements, that is not required to be CCPs, in regard to the applicable process and end product.

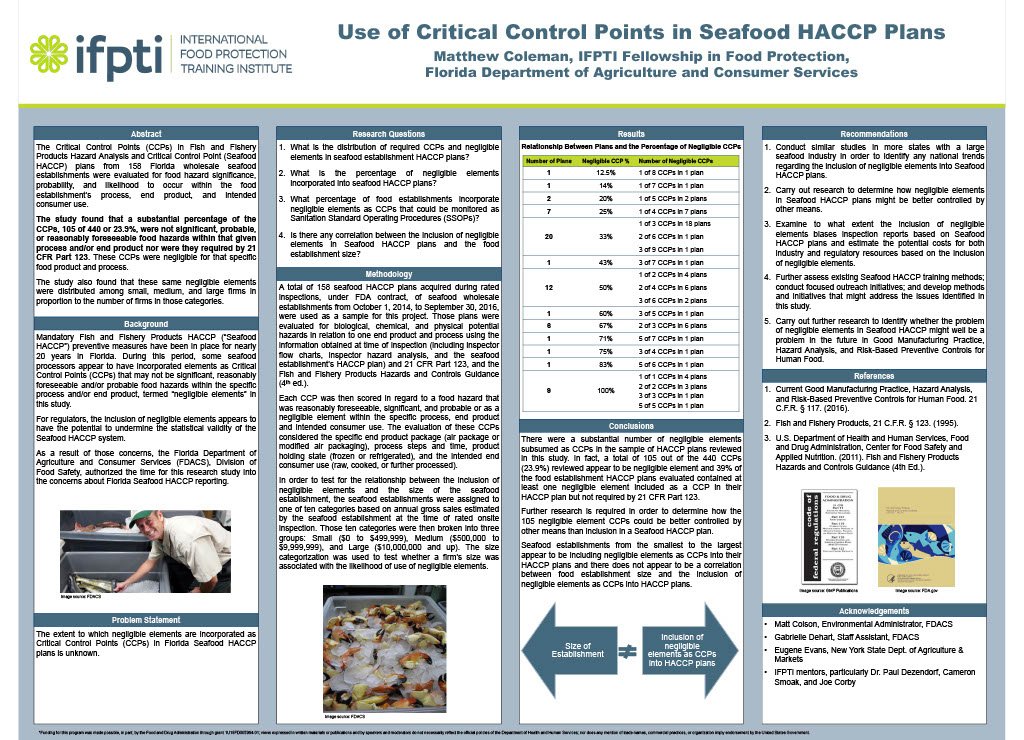

These 105 negligible element CCPs, not required by 21 CFR Part 123, were found in 63 of the 158 HACCP plans (39%) evaluated. The percentage of CCPs not required in a HACCP plan ranged from 12.5% to 100% of the total CCPs in the food establishment’s plan. Table 1 presents the relationship between the percentage of negligible CCPs and the number of plans.

Table 1

Relationship Between Number Plans and the Percentage of Negligible CCPs

All the CCPs in nine of the 63 plans (14.3%) were negligible elements. In most of these cases, the seafood establishment (secondary receiver) received frozen product, did not further process or re-label, and shipped back out the frozen product, e.g. box-in, box-out products. In other words, the probability of significant food hazards occurring while in an unchanged frozen state is not reasonably foreseeable and thus any CCP is a negligible element.

Some of examples of negligible elements included as CCPs in the HACCP plans reviewed:

· Metal inclusion – knives used with manual cutting of fish

· Cooling – rapidly cooled cooked seafood to safe temperatures within 2 hours

· Allergen labeling – within a single ingredient fish end product

· Storage – product held in a frozen state

· Clostridium botulinum – for an end product air packed

· Receiving – incoming product received in a frozen state

· Processing – histamine time control with brief processing steps

Small seafood establishments made up 20% of the 158 plans examined in the study; medium size seafood establishments comprised 57%; and 23% were large. Table 2 further illustrates percentage of HACCP plans by food establishment size.

Table 2

HACCP Plans by Food Establishment Size

Conclusions

There were a substantial number of negligible elements subsumed as CCPs in the sample of HACCP plans reviewed in this study. In fact, a total of 105 out of the 440 CCPs (23.9%) reviewed appear to be negligible element and 39% of the food establishment HACCP plans evaluated contained at least one negligible element included as a CCP in their HACCP plan but not required by 21 CFR Part 123.

Further research is required in order to determine how the 105 negligible element CCPs could be better controlled by other means than inclusion in a Seafood HACCP plan.

In conclusion, there does not appear to be a correlation of food establishment size and the inclusion of negligible elements as CCPs into HACCP plans. In other words, seafood establishments from the smallest to the largest appear to be including negligible elements as CCPs into their HACCP plans.

Recommendations

1. A similar study should be carried out in one or more states with a large seafood industry in order to identify whether the conclusions here are particular only to Florida or may indicate a national pattern of including negligible elements into Seafood HACCP plans.

2. Future research should examine how negligible elements in Seafood HACCP plans might be better controlled by other means.

3. Further research should examine to what extent the inclusion of negligible elements biases inspection reports based on Seafood HACCP plans as well as estimating the potential costs of that bias in terms of industry and regulatory resources. The relationship between steps unnecessarily incorporated as CCPs as compared with addressing these lesser food elements by other means needs further in-depth research. In doing so, such research might assess the potential detraction from the qualitative statistical approach of HACCP as well as unnecessary use of industry and regulatory resources when these lesser elements steps are incorporated as CCPs.

4. Further research should examine opportunities to either identify existing Seafood HACCP training methods and focused outreach initiatives or develop methods and initiatives that might address the issues identified in this study.

5. Further research also should examine whether the problem of negligible elements in Seafood HACCP might well be a problem in the future in Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food in order to incorporate changes into training methodology for industry and regulators.

The intention is to apply some of the above recommendations and take action in Florida. Specifically, focused outreach activities to those seafood processors that were identified during this research to have incorporated negligible elements as CCPs within their HACCP plans. Additionally, outreach initiatives to broach this subject with various seafood industry associations is already in the making.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the following individuals and their respective agencies for their assistance during this study. First and foremost, to Matt Colson, Environmental Administrator of FDACS for his assistance with the FDACS Food Inspection Management System; Gabrielle Dehart, Staff Assistant, for her assistance in compiling and organizing the large number of individual documents in the study; Merrill Emfinger, formerly of FDACS, for his assistance in categorizing firm size; as well as to Eugene Evans with New York Agriculture and Markets for being a never-ending sounding board and source of feedback. Finally, to IFPTI for the support from Dr. Paul Dezendorf, Cameron Smoak, and Joe Corby throughout the project.

References

Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food. 21 C.F.R. § 117. (2016).

Fish and Fishery Products, 21 C.F.R. § 123. (1995).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. (2011). Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance (4th Ed.). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceRegulation/UCM251970.pdf