Food Safety Compliance: A Comparison of New Hampshire Restaurants Based on Ethnic Cuisine Categorization

Kristin M. DeMarco Shaw

Health Inspector

Public Health Department/City of Portsmouth, NH

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2011 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

The diversification of the nation continues to evolve, and the population changes in New Hampshire mirror trends taking place across the United States. Although the state’s population growth rate is slower than that of the nation, New Hampshire’s growth is driven by increases in minority populations (Moore, 2011). The U.S. food service industry employs the highest percentage of foreign-born workers compared with other U.S. industries and this percentage is projected to steadily increase in the next decade (Mauer et al., 2006, National Restaurant Association, 2012). Restaurants are often identified as the source of confirmed foodborne illness-related outbreaks, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2004 that outbreaks associated with ethnic foods were on the rise (Simonne, 2004). The ethnic food market in New Hampshire continues to grow. This study was designed to identify consistencies in violations cited on inspection of full-service restaurants across New Hampshire and to determine if compliance with the Food Code differs by ethnic cuisine categorization. An analysis of statewide inspection data indicates that the most common violations cited in ethnic restaurants in New Hampshire are for failure to prevent food contamination, poor personal hygiene, and improper temperature control of potentially hazardous foods. However, the results also indicated that issues with hand washing and other good hygienic practices are widespread in the entire food industry, demonstrating a lack of knowledge of safe food handling practices across all restaurant types.

Food Safety Compliance: A Comparison of New Hampshire Restaurants Based on Ethnic Cuisine Categorization

Background

The U.S. Census Bureau has projected that minorities, who currently make up roughly one-third of the U.S. population, will become the majority in 2042 (Bernstein and Edwards, 2008). This increase in ethnic and racial diversity in America is best illustrated by the food service industry, which employs the highest proportion of foreign-born workers within U.S. industries (Mauer et al., 2006). According to the National Restaurant Association (NRA), foreign-born workers account for approximately 25% of food service manager positions and fill approximately 25% of employee positions in food-based occupations. Growth within the restaurant industry is following a similar trend; and 1.4 million jobs are expected to be added to the food industry by 2022 (National Restaurant Association, 2012).

The restaurant industry continues to be an integral part of daily life in the U.S., with over 70 billion meal and snack options served to consumers in 2010 (National Restaurant Association, 2011). A report published by the NRA indicates that “an average of one out of five meals consumed by Americans—4.2 meals per week—is prepared in a commercial setting” (Ebbin, 2000). In 2008, 52% of confirmed foodborne illness-related outbreaks reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were caused by food consumed in a restaurant or deli (Gould et al., 2011). Separate studies conducted by FoodNet indicated an association between foods consumed outside of the home and “an increased risk for specific foodborne illnesses” (Hedburg et al., 2006). The CDC also reported that foodborne illness outbreaks associated with ethnic foods increased 7% between 1990 and 2000. Most of these outbreaks were linked to Mexican, Italian, and Asian foods, and 43% of all of the outbreaks were attributed to food served in a restaurant (Simonne, 2004). Safe food-handling practices in restaurants are critical to the prevention of foodborne disease transmission and protection of public health.

During the last decade, certain ethnic cuisines have become so popular that they are now considered mainstream. This interest in ethnic foods has led to growth in the number of culturally-focused food establishments, markets, and products. U.S. census data for 2010 indicate that ethnic populations in New Hampshire have increased 2.1% since 2000. First-generation owners and operators of ethnic stores and restaurants tend to lack knowledge of safe food practices (Po, L. G., Bourguin, Occeea, and Po, E. C., 2011). Several studies have been conducted to examine food-handling practices in ethnic restaurants. Mauer et al. (2006) identified improper food temperature control, cross-contamination, and poor hygiene as the most common violations cited in ethnic restaurant operations. Studies by Kwon, Roberts, Shanklin, Liu, and Yen (2010) and Roberts, Kwon, Shanklin, Liu, and Yen (2011) supported these findings and reported that ethnic restaurants were cited for more violations of the Food Code, both critical and non-critical, than non-ethnic restaurants, and experienced a greater frequency of inspection. Both studies stressed the need for food safety training programs that focus on behaviors that could lead to foodborne illness outbreaks in these restaurants.

The CDC surveillance report for 1993-1997 identified food preparation practices and employee behaviors as the most frequently reported contributing factors to foodborne illness (Olsen, 2000). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) further defined five of the categories that directly relate to food safety within retail food establishments as “foodborne illness risk factors.” These five categories are as follows: Food from Unsafe Sources, Inadequate Cooking, Improper Holding Temperatures, Contaminated Equipment, and Poor Personal Hygiene. These categories are composed of many of the 44 standards (Food Code requirements) that are used by regulatory agencies to monitor food safety compliance within food service establishments.

Problem Statement

Restaurants that serve ethnic cuisine are increasing in New Hampshire, and identification of specific behaviors and practices that are most often out of compliance with Food Code requirements will allow food safety professionals to improve the safety of foods prepared and sold at these establishments. This study is designed to identify consistencies in violations found during inspections of full-service restaurants across New Hampshire and to determine if compliance with the Food Code differs among restaurant types.

Research Questions

1. What violations are most often cited in full-service restaurants in New Hampshire?

2. Do differences in compliance with the Food Code exist among restaurant types?

3. How do the cited violations correlate with the CDC-identified foodborne illness risk factors?

Methodology

The study population was defined as full-service restaurants in New Hampshire that prepare and serve potentially hazardous food and drinks on premises and that may also offer takeout and/or delivery service. The restaurant types were classified in one of the following categories: Indian, Hispanic/Mexican, Asian (Chinese and Japanese only), corporate, or non-ethnic local. Areas of the state with greater population densities were identified, and restaurants that met the study criteria were randomly selected from these jurisdictions. A secondary data analysis was conducted using statewide restaurant inspection data collected from January 2009 through December 2010. All routine inspections during this period were included in the analysis. Inspections were performed by New Hampshire Food Protection Section Food Safety Coordinators or by local health department employees (depending on jurisdiction) in accordance with rules set forth in the New Hampshire Rules for the Sanitary Production and Distribution of Food (He-P2300).

Inspectors used standardized forms that included 44 items (standards); 13 items were designated as “critical.” Critical items are violations “which [are] more likely than other violations to contribute to food contamination, illness, or environmental health hazard[s]” (He-P2300). Inspection reports also contained data such as specific violations cited, facility name and address, and overall score. For comparison purposes, a sample of 174 inspections from 35 restaurants (seven restaurants per food type) that met the study population criteria was analyzed. Data were entered into a spreadsheet and analyzed with Microsoft Excel.

Results

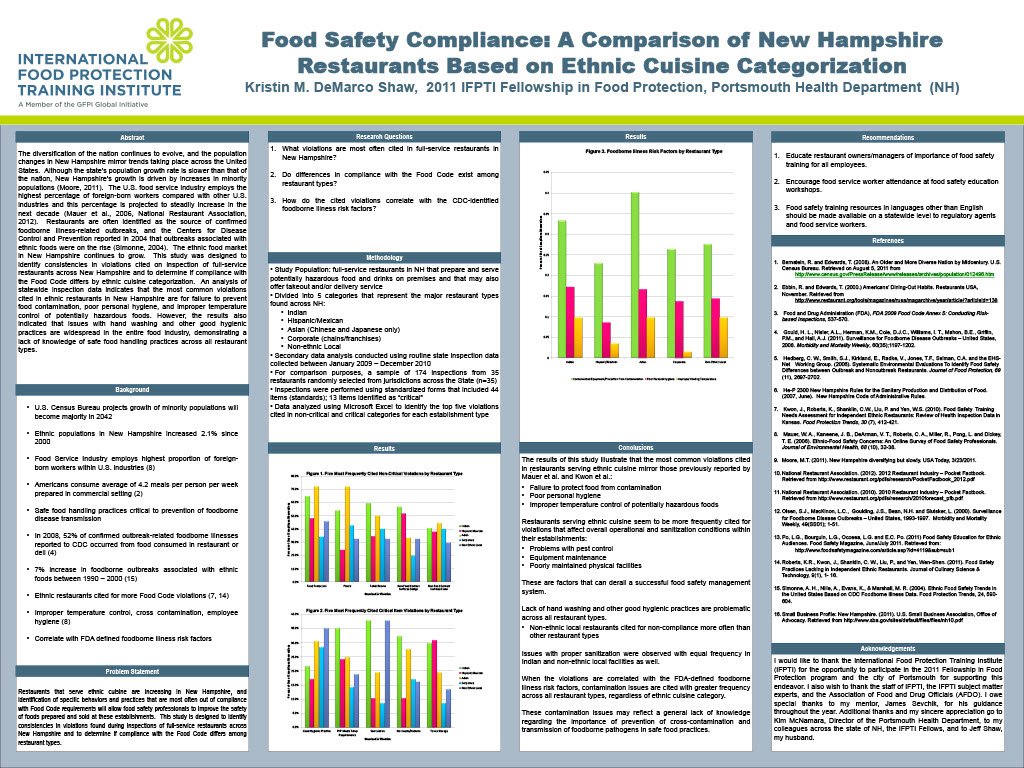

Analysis of the routine inspection reports indicated that the most commonly cited violations for all restaurant types were for failure to protect food from contamination during storage, preparation, display, service and/or transportation (53.5%, n = 93), followed by floors that were unclean, improperly constructed, and/or in poor repair (45.9%, n = 80). Neither of these violations is designated as a critical item violation. Figure 1 illustrates the five most frequently cited non-critical violations observed over the study period for each restaurant category identified.

As Figure 1 illustrates, Asian restaurants were cited most frequently for lack of compliance with three of the five standards: food protection from contamination (72.2%), maintenance of floors (72.2%), and cleanliness of non-food contact surfaces of equipment and utensils (44.4%), while Indian restaurants were cited most frequently for lack of compliance with the remaining two standards: issues with toilet rooms (59.5%) and the design, construction, or maintenance of non-food contact surfaces (56.8%). Violations for food protection, unclean/unstocked toilet rooms, and unclean non-food contact surfaces of equipment and utensils are violations that contribute to several of the foodborne illness risk factors described by the FDA. Issues with floor design and cleanliness or the misuse or poor design of non-food contact equipment and utensils are indicators of weaknesses in Good Retail Practices (GRPs) that could result in conditions that may lead to foodborne illness (FDA Food Code, Annex 5, 2009).

Lack of hand washing and other good hygienic practice was the most frequently cited critical item violation overall (27.01%, n = 47). Figure 2 illustrates the five critical item violations most frequently cited for each restaurant type.

Although good hygienic practice was cited most frequently overall, issues with sanitization were cited most often with equal frequency (37.8%) in Indian and non-ethnic local restaurants when the violation is considered by restaurant type. Indian restaurants were also cited most often for temperature abuse of potentially hazardous foods (PHF) (35.1%) and issues with pest control and abatement (32.4%). Non-ethnic local restaurants violated the standard for good hygienic practices most often (35.1%), while Hispanic/Mexican restaurants were cited most frequently for problems with toxic storage and labeling (31.0%).

Six of the 10 violations illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 can be categorized under three of the foodborne illness risk factors. Violations for food protection, issues with sanitization, and unclean non-food contact surfaces of equipment contribute to the “Contaminated Equipment” risk factor. The “Poor Personal Hygiene” risk factor includes violations for adequate hand washing and good hygienic practices as well as hand-washing facility functionality. And the “Improper Holding” risk factor represents potentially hazardous foods that are kept out of temperature.

Conclusions

The results of this study illustrate that the most common violations cited in ethnic restaurants in New Hampshire mirror those previously reported by Mauer et al. and Kwon et al.: failure to protect food from contamination, poor personal hygiene, and improper temperature control of potentially hazardous foods. Ethnic restaurants also seem to be more frequently cited for violations that affect the overall operational and sanitization conditions within their establishments. Problems with pest control, equipment maintenance, and poorly maintained physical facilities are factors that can derail a successful food safety management system.

However, this study also indicates that lack of hand washing and other good hygienic practices are problematic across all restaurant types, and when broken down by ethnic cuisine category, non-ethnic local restaurants are cited for non-compliance more often than any other restaurant type. Issues with proper sanitization were observed with equal frequency in Indian and non-ethnic local facilities as well. When the violations are correlated with the FDA-defined foodborne illness risk factors, contamination issues are cited with greater frequency across all restaurant types, regardless of ethnic cuisine category. These contamination issues may reflect a general lack of knowledge regarding the importance of prevention of cross-contamination and transmission of foodborne pathogens in safe food practices.

Recommendations

Although food safety training and certification are not required for food service employees in New Hampshire, food service workers must be encouraged to attend food safety education workshops whenever possible. Lack of resources is often cited as a barrier to adequate food safety training. However, food safety training workshops that focus on the importance of good hygienic practices and controlling for contamination and temperature are offered free of charge to food facilities in New Hampshire by the Cooperative Extension Services. Food safety training resources in languages other than English should be made available on a statewide level to regulatory agents and food service workers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) for the opportunity to participate in the 2012 Fellowship in Food Protection program and the city of Portsmouth for supporting this endeavor. I also wish to thank the staff of IFPTI, the IFPTI subject matter experts and the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO). I owe special thanks to my mentor, James Sevchik, for his guidance and support throughout the year. Additional thanks and my sincere appreciation go to Kim McNamara, Director of the Portsmouth Health Department, and my colleagues across the state of New Hampshire for their contributions to this project. Special thanks also go to the IFPTI Fellows and to Jeff Shaw, my husband.

Corresponding Author

Kristin DeMarco Shaw, Public Health Department, City of Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Email: kmshaw@cityofportsmouth.com

References

Bernstein, R. and Edwards, T. (2008). An older and more diverse nation by midcentury. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on August 5, 2011 from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html

Ebbin, R. (2000). Americans’ Dining-Out Habits. Restaurants USA, November. Retrieved from http://www.restaurant.org/tools/magazines/rusa/magarchive/year/article/?articleid=138

Gould, H. L., Nisler, A. L., Herman, K. M., Cole, D. J. C., Williams, I. T., Mahon, B. E., Griffin, P. M., and Hall, A. J. (2011). Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(35);1197-1202.

Hedberg, C. W., Smith, S. J., Kirkland, E., Radke, V., Jones, T. F., Selman, C. A., and the EHS-Net Working Group. (2006). Systematic environmental evaluations to identify food safety differences between outbreak and nonoutbreak restaurants. Journal of Food Protection, 69(11), 2697-2702.

He-P 2300 New Hampshire rules for the sanitary production and distribution of food (2007, June). New Hampshire Code of Administrative Rules.

Kwon, J., Roberts, K., Shanklin, C. W., Liu, P., and Yen, W. S. (2010). Food safety training needs assessment for independent ethnic restaurants: Review of health inspection data in Kansas. Food Protection Trends, 30(7), 412-421.

Mauer, W. A., Kaneene, J. B., DeArman, V. T., Roberts, C. A., Miller, R., Pong, L. and Dickey, T. E. (2006). Ethnic food safety concerns: An online survey of food safety professionals. Journal of Environmental Health, 68(10), 32-38.

Moore, M. T. (2011, March 23). New Hampshire diversifying but slowly. USA Today.

National Restaurant Association. (2012). 2012 restaurant industry pocket factbook. Retrieved from http://www.restaurant.org/pdfs/research/PocketFactbook_2012.pdf

National Restaurant Association. (2010). 2010 restaurant industry pocket factbook. Retrieved from http://www.restaurant.org/pdfs/research/2010forecast_pfb.pdf

Olsen, S. J., MacKinon, L. C., Goulding, J. S., Bean, N. H., and Slutsker, L. (2000). Surveillance for foodborne disease—United States, 1993-1997. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 49(SS01), 1-51.

Po, L. G., Bourguin, L. G., Occeea, L. G. and Po, E. C. (2011, June/July). Food safety education for ethnic audiences. Food Safety Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/article.asp?id=4119&sub=sub1

Roberts, K. R., Kwon, J., Shanklin, C. W., Liu, P., and Yen, W. S. (2011). Food safety practices lacking in independent ethnic restaurants. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 9(1), 1-16.

Simonne, A. H., Nille, A., Evans, K., and Marshall, M. R. (2004). Ethnic food safety trends in the United States based on CDC foodborne illness data. Food Protection Trends, 24, 590-604.

Small business profile: New Hampshire. (2011). U.S. Small Business Association, Office of Advocacy. Retrieved from http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/nh10.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2009). FDA 2009 Food Code Annex 5: Conducting Risk-based Inspections, 537-570.