Food Safety Compliance Levels Among Tribal Nations in the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service

LT Aaron McNeill

Environmental Health Officer

Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service—Division of Environmental Health Services

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2011 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Abstract

This research paper will focus on how the adoption or implementation of a food code affects the compliance levels, food safety risk factors, and critical violations of American Indian food service operations within the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service (OCAIHS) region. In the OCAIHS region, 28 tribal nations prepare food for the general public. The majority of these tribes have neither adopted nor formally implemented the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s model Food Code, the Oklahoma State Food Sanitation Code, or a tribal food code as a tool to address food safety principles.

This research focused on tribal food service operations located in the Pawnee and Miami Service Units of the OCAIHS. In 2010, a total of 3,566,315 meals were served from the food service operations located within these two Service Units.

Completion of the data analysis revealed that there was an increase in the level of compliance and reduction in risk factors and critical violations in food establishments that have adopted or implemented a model of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s model Food Code.

Background

According to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) gets foodborne illness each year, 128,000 are hospitalized for these diseases, and 3,000 die of these illnesses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011).

Twenty-eight American Indian tribes within the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service (OCAIHS) region prepare food for tribal citizens and the general public. The tribes receive direct environmental health services, including food sanitation, by professional environmental health officers of the OCAIHS. One objective of the OCAIHS‘s Division of Environmental Health Services (DEHS) is to prevent and control foodborne illness risk factors among the American Indian population and among the general public. The DEHS staff fulfills this objective by conducting routine food sanitation surveys and food handler training for tribal food establishment personnel. The majority of tribes served by the OCAIHS have not adopted the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) model Food Code, the State of Oklahoma Food Sanitation Code, or a tribal food code.

The tribes served by the OCAIHS are not subject to food safety laws, standards, or policies established by a local or state government due to tribes’ independent sovereign nation status recognized by the United States government. The tribes and the federal government function according to a government-to-government relationship. This unique relationship gives tribes sovereignty and sole authority to enact their own laws and policies regarding their government, citizens, programs, and business entities within their jurisdictional boundaries. Several tribal programs, such as Head Start, Office of Child Care, and Elderly Nutrition Title VI programs, receive federal funding. For this reason, these programs may be required to follow federal mandates that address food safety in order to receive or maintain funding.

Federally recognized tribal nations in the OCAIHS are treated as sovereign nations by the United States government and are not subject to state food safety laws unless they choose to be subject to them through tribal government resolution, law, or policy. On the other hand, there are instances in which a tribal program, such as a tribal Head Start Center, may receive federal funding or a grant and may be required to adhere to federal mandates addressing food safety in order to receive or maintain the federal funding. Tribal gaming operations receive federal oversight by the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC) and its Environmental, Public Health, and Safety (EPHS) standards. The EPHS standards are designed to ensure that Indian gaming facilities have tribal ordinances, laws, or regulations to protect the environment and the s public health and safety, including food safety.

On October 17, 1988, Congress enacted the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, 25 U.S.C. 2701-21, which created the NIGC. The NIGC was granted oversight and enforcement authority to monitor tribal gaming operations. This oversight and enforcement authority included establishing EPHS standards designed to ensure that Indian gaming facilities have tribal ordinances, laws, or regulations to protect the environment and the public health and safety. Pursuant to Chapter 25 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), CFR 502.22 and 559.5, tribal gaming operations must identify the existing laws, resolutions, codes, policies, standards, or procedures and certify compliance with and enforcement of those laws, resolutions, codes, policies, standards, or procedures inherent to the EPHS standards. Tribal gaming operations identifying and certifying compliance with and enforcement of the model FDA Food Code would be an example of meeting the CFR requirement indicated above. If an ordinance, law, or regulation is found to be in noncompliance, the NIGC has authorization to undertake enforcement actions, including citing violations, assessing civil fines, and/or issuing closure orders.

The National Environmental Health Association (NEHA) position paper titled “Retail food protection on the local, state, and tribal levels: Left out of the new federal food protection initiatives?” discusses steps that are needed to develop a successful national retail food protection system. According to the NEHA Food Safety Committee, nationwide adoption of the latest FDA Food Code is required for uniformity of standards among the ranks.

The model FDA Food Code establishes practical, science-based guidance and enforceable provisions for mitigating risk factors known to cause foodborne illness. Adoption and implementation of the model FDA Food Code supports achieving uniform national food safety standards and enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of the food safety system (2009 Food Code). Tribal governments have the autonomy to support the framework of the uniformity of national food standards by choosing to adopt or develop food code standards based on the most recent FDA Food Code. The uniformity of standards within all tribal food service operations would be strengthened and create more consistency within themselves and with neighboring nontribal food service establishments.

Problem Statement

Eight percent of tribal nations with foodservice operations located within the OCAIHS service area have adopted or developed food code standards based on the Model FDA Food Code. The implementation of a food code modeled after the most recent FDA Food Code could lead to uniformity in national food safety standards and increase the effectiveness of a food safety system. This research project compared food safety risk factor violations in food service establishments having an adopted food code to violations in establishments that have not implemented any form of the model FDA Food Code.

Research Questions

1. Does the adoption of an approved food code increase or decrease the level of compliance in addressing FDA foodborne illness risk factors?

2. How do critical violations compare between food establishments with a food code to those having no food code?

Methodology

Research was conducted via a Web-based environmental health reporting system called WebEHRS. The WebEHRS database is a program designed by the Indian Health Service to input and track environmental health-related activities. WebEHRS allows users to set filters to produce various reports from the data that are entered into the system. For food service surveys, WebEHRS uses the 2001 FDA Food Code. The data generated from WebEHRS involved tribes in two different service units and were entered by two different environmental health officers who have been standardized in the FDA food inspection protocol.

The reporting filters used in this research included tribal nation, establishment type, and risk factor violations from January 2010 through October 2011. Four tribal nations were selected for comparison. Two of the four tribes had adopted the model FDA Food Code. All four tribes had a comparable number of food establishments. The two tribes that had adopted the model FDA Food Code had 16 food service operations, while the two tribes with no food code had 19 food service operations. Additional factors for comparing the tribes and facilities were based on near equivalency in the total number of food service operations within a gaming facility and nongaming food service operations.

Facility Types 47 and 80 were selected. Facility Type 47 refers to a stand-alone café/restaurant or a food establishment located within a tribal gaming facility. Facility Type 80 refers to a food service operation that provides meals to clientele of a tribal program or nongaming facility. Facility Type 80 operations include kitchens located in Head Start centers, day care centers, senior centers, and community buildings.

Regarding food safety and associated foodborne illness concerns, the model FDA Food Code lists the leading food safety risk factors associated with foodborne illness as improper holding temperatures, inadequate cooking, contaminated equipment, food from unsafe sources, and poor personal hygiene. A critical violation refers to a provision of the FDA Food Code that, if in noncompliance, would more likely than other violations contribute to food contamination, illness, or an environmental health hazard.

Results

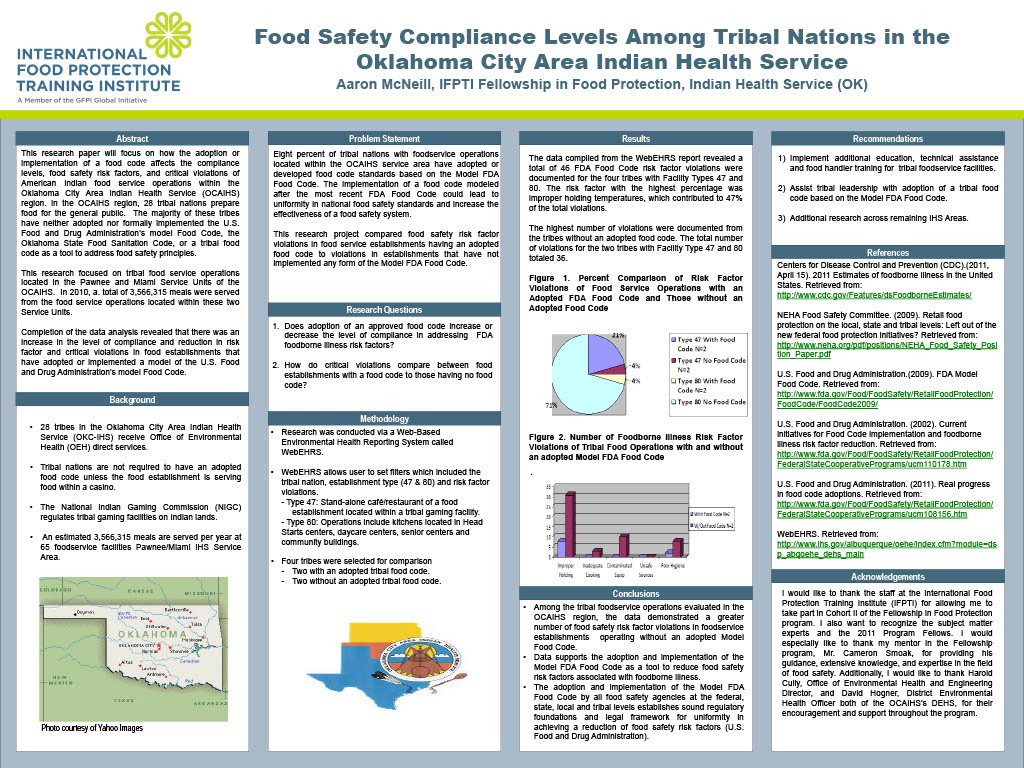

From January 2010 through October 2011, a total of 46 FDA Food Code risk factor violations were documented for four tribes with Facility Types 47 and 80. The risk factor violations occurred at both gaming and nongaming food service operations. The risk factor with the highest percentage of violations was improper holding temperatures. Improper holding temperatures contributed to 47% of the total violations documented during calendar year 2010. Over the course of the year, food from unsafe sources and inadequate cooking temperatures had the fewest documented violations for all facility types and groups.

The data compiled from the WebEHRS report revealed interesting results when comparing tribes with an adopted food code to those without one. The total number of violations in the WebEHRS report for the two tribes without an adopted food code with Facility Type 47 and Facility Type 80 food service operations totaled 36. The majority of the risk factor violations were found within the Facility Type 47 operations, because there were more facilities of that type than Facility Type 80 operations.

Figure 1 illustrates that food service operations that utilize the model FDA Food Code had a lower percentage (21%) of risk factor violations than did those without a food code (79%).

Although foodservice establishments which are operated by a tribal nation with an adopted food code had fewer risk factor violations in comparison to those without an adopted food code, Figure 2 shows little difference in the areas of inadequate cooking and food from unsafe sources. The foodservice establishments operated by a tribal nation without an adopted food code had a higher number of violations of improper holding temperatures, contaminated equipment, and poor personal hygiene.

Conclusions

Among the tribal food service operations evaluated in the OCAIHS region, the data demonstrated that a greater number of documented food safety risk factor violations occurred in foodservice establishments operated by tribal nations without an adopted model FDA Food Code than in those with an adopted model FDA Food Code. The data supports the adoption and implementation of the model FDA Food Code as a tool to reduce food safety risk factors associated with foodborne illness. The adoption and implementation of the model FDA Food Code by all food safety agencies at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels establishes a sound regulatory foundation and legal framework for uniformity in achieving a reduction of these risk factors (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2011, p. 2).

Recommendations

Additional research by other Indian Health Service (IHS) areas would be required to determine if the data results are similar across the country. This information could help provide the data that IHS and environmental health officers need to assess whether there is a correlation between the increase of food safety risk factor violations and possible foodborne illness cases within tribal food service operations that have not adopted a model of the FDA Food Code. If further studies of this type are conducted and such a correlation is found, it could be a factor in support for the adoption of the model FDA Food Code by all food safety agencies at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels. Adoption and implementation would allow for a national retail food system with uniform food code standards to achieve a reduction of food safety risk factors.

As sovereign entities, Indian tribes have a unique opportunity to empower themselves in their initiatives to promote and protect the health and safety of their citizens. An ongoing study of this topic could provide valuable data and documentation that could be presented to tribal councils and tribal leaders to help persuade them to adopt tribal food codes based on the model FDA Food Code.

In the meantime, steps can be taken to reduce the number of food safety risk factor violations. Food safety education, technical assistance, and food handler training should continue to be provided to tribal food service operations. Attention should be focused on reducing the leading FDA risk factors having the highest percentage of violations and encouraging safeguards that will lead to a decrease in risk factor violations that cause foodborne illness.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the staff at the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) for allowing me to take part in Cohort II of the Fellowship in Food Protection program. I also want to recognize the subject matter experts and the 2011 Program Fellows. I would especially like to thank my mentor in the Fellowship program, Mr. Cameron Smoak, for providing his guidance, extensive knowledge, and expertise in the field of food safety. Additionally, I would like to thank Harold Cully, Office of Environmental Health and Engineering (OEHE) Director, and David Hogner, District Environmental Health Officer, both of the OCAIHS’s DEHS, for their encouragement and support throughout the program.

Corresponding Author

Aaron McNeill, Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service—Division of Environmental Health Services

Email: aaron.mcneill@ihs.gov

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011, April 15). 2011 estimates of foodborne illness in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsFoodborneEstimates/

NEHA Food Safety Committee. (2009). Retail food protection on the local, state and tribal levels: Left out of the new federal food protection initiatives? Retrieved from

http://www.neha.org/pdf/positions/NEHA_Food_Safety_Position_Paper.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009). FDA Model Food Code. Retrieved from

http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/FoodCode/FoodCode2009/

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2002). Current initiatives for Food Code implementation and foodborne illness risk factor reduction. Retrieved from

http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/FederalStateCooperativePrograms/ucm110178.htm

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011). Real progress in food code adoptions. Retrieved from

http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/RetailFoodProtection/FederalStateCooperativePrograms/ucm108156.htm

WebEHRS. Retrieved from http://www.ihs.gov/albuquerque/oehe/index.cfm?module=dsp_abqoehe_dehs_main